Biological sex isn't always written in stone. Not in the way you might think after watching a thirty-minute episode of Bones or CSI. You see a pelvis on screen, the lead investigator points at a wide subpubic angle, and boom—it's a female. Easy. Right?

Honestly, it’s rarely that simple.

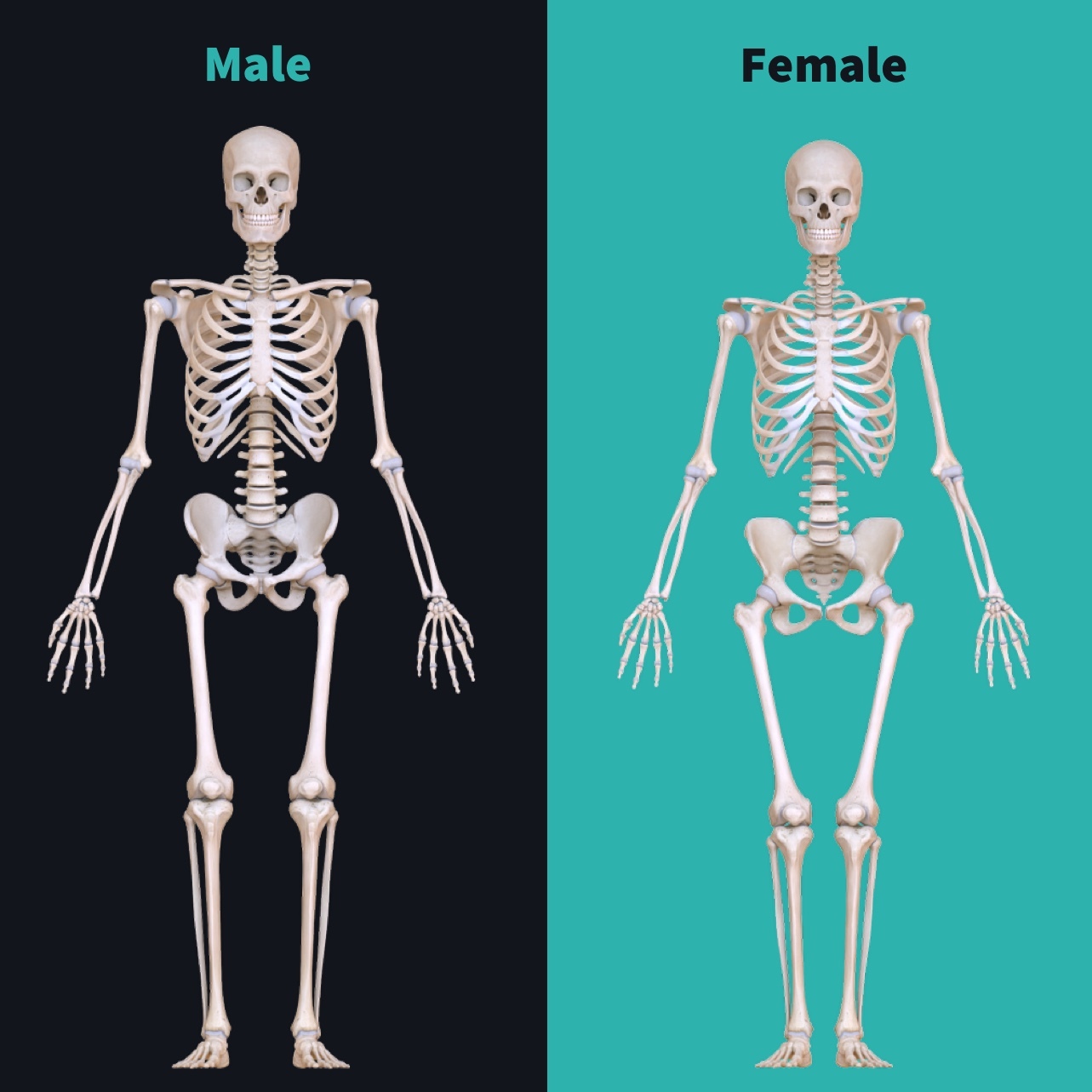

The human skeleton is a weird, plastic thing. It changes based on what you eat, how hard you work, and the specific genetic lottery you won at birth. When we talk about a skeleton female and male, we are talking about a spectrum of morphological traits, not a binary set of "pink and blue" bones. Forensic anthropologists like Dr. Elizabeth DiGangi or the late, legendary Bill Bass have spent decades proving that while the "average" male and female skeletons look different, the "average" person is actually quite hard to find.

The Pelvis is the Smoking Gun (Mostly)

If you’re trying to tell if a skeleton is male or female, you start at the hips. This is the only part of the human body where biological function—specifically childbirth—forces a massive evolutionary divergence.

The female pelvis is built for passage. It’s wider, shallower, and the pelvic inlet (the "hole" in the middle) is generally circular or oval. Men don’t have to push a seven-pound human through their midsection. Because of that, the male pelvis is narrow, heavy, and deep. It’s built for support and bipedal efficiency, looking more like a heart shape from above.

Look at the Greater Sciatic Notch.

If you pick up a pelvic bone (the os coxa), there’s a big "hook" on the back. In a female skeleton, this notch is typically wide—you can almost fit three fingers in there and wiggle them around. In a male, it’s narrow, often looking like a tight "U" or even a "V." But here’s the kicker: age changes this. A malnourished male might have a wider-looking notch, or an older female who never bore children might have denser, more "masculine" bone structure.

Then there’s the Phenice Method. Back in 1969, T.W. Phenice identified three specific features on the pubic bone: the ventral arc, the subpubic concavity, and the medial aspect of the ischiopubic ramus. It sounds like a mouthful, but it’s basically just looking for specific ridges of bone that develop under the influence of estrogen. It’s incredibly accurate—around 95%—but only if the pelvis is intact.

Nature is rarely that kind to forensic teams.

✨ Don't miss: Eugenics Meaning in English: Why This Dark Concept Still Haunts Modern Science

The Skull Tells a Different Story

Skulls are deceptive. You’d think the head would be the easiest part to identify, but the skull is more about muscle attachments than reproductive biology.

Males generally have "more" of everything on the skull. More prominent brow ridges (supraorbital tori). A more pronounced "bump" on the back of the head (the nuchal crest) where neck muscles attach. A more square, "blocky" chin. If you feel the top edge of your eye socket, and it feels dull or rounded, that’s a classically male trait. A sharp, "knife-like" edge is typically female.

But wait.

Have you ever seen a very athletic woman? Or a man with a very slight build?

Bone reacts to stress. If a female spends her life doing heavy manual labor, her muscle attachment sites—like the mastoid process (that bone behind your ear)—will grow larger and more rugged to support the extra muscle tension. Suddenly, her "female" skull starts looking very "male" to an untrained eye.

Standardization is the enemy of accuracy here. We use a 1 to 5 scale for these traits, where 1 is hyper-feminine and 5 is hyper-masculine. Most people? They’re 2s, 3s, and 4s. They are "probables," not "certains."

Why Population Data Changes Everything

You cannot use the same metrics for a skeleton from 14th-century Norway and a skeleton from modern-day Tokyo.

Size is relative. A "large" female skeleton in one population might be significantly smaller than a "small" male skeleton in another. Forensic anthropologists use things like the FORDISC software—developed at the University of Tennessee—to compare measurements against specific databases.

If you find a femur that is 450mm long, that doesn't tell you the sex until you know the ancestry. In some groups, that’s a tall woman; in others, it’s a short man. This is where "Big Data" meets old-school anatomy. We have to account for secular trends. People are getting taller and heavier than they were 200 years ago. Our bones are actually becoming less robust because we aren't chasing mammoths or tilling fields by hand anymore. This "gracilization" of the human skeleton makes distinguishing between a skeleton female and male harder every year.

The Limits of the Naked Eye

We have to talk about the "Grey Zone."

About 10% to 15% of skeletons are what experts call "indeterminate." The pelvis says female, but the skull says male. Or the bones are so fragmented from fire, water, or time that the diagnostic landmarks are gone.

In these cases, we look at the humerus (upper arm) or the femur (thigh) head. The diameter of the "ball" that fits into the socket is a decent secondary indicator. Men typically have larger joints because they have more body mass to support.

But even this has limits.

💡 You might also like: Tick bite rash photos: Why your skin might be lying to you

What about juveniles? This is the dirty secret of forensic anthropology: you can't really sex a child's skeleton. Until puberty hits and the hormones start "sculpting" the bone, boys and girls look almost identical skeletally. Unless you have DNA, identifying the sex of a prepubescent skeleton is mostly guesswork.

The Modern Reality: Beyond the Binary

In 2026, the field is shifting. We are moving away from forcing every set of remains into a strict male/female box.

Why? Because biological variation is real. There are intersex conditions that affect bone development. There are hormonal treatments that can change bone density and muscle attachment sites over time. While the "hard" structures of the pelvis usually remain the most reliable markers, experts are becoming much more cautious about "calling it" too early.

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History houses the Terry Collection—thousands of skeletons where the sex, age, and cause of death are known. Researchers use this to refine their techniques. They’ve found that even with the best training, there is always a margin of error.

If a skeleton is missing its pelvis, the accuracy of sexing the remains drops from nearly 95% to somewhere around 80%. That’s a one-in-five chance of being wrong. In a criminal trial, those odds are terrifying.

Actionable Steps for Identifying Skeletal Remains

If you are a student, a writer, or just someone deeply curious about the reality of human osteology, stop looking for "one-size-fits-all" answers. Instead, focus on the weight of evidence.

1. Prioritize the Pelvis

Look for the subpubic angle. If it’s wider than 90 degrees (like an "L" on its side), it’s likely female. If it’s narrow like a "V," it’s likely male. This remains the gold standard.

📖 Related: I Got Pregnant From Precum Forum: Why It Happens and What the Science Says

2. Check the "Robusticity" Balance

Don't look at one bone. Look at the whole picture. Is the skull rugged but the long bones slender? You might be looking at a population-specific trait rather than a sex trait.

3. Use Metric Analysis

Forget "looking" at it. Get the calipers out. Use established tables (like those from Bass or Ubelaker) to measure the diameter of the femoral head. If the diameter is over 45mm, it’s statistically more likely to be male in most Western populations.

4. Acknowledge Ancestry First

Before you decide if a skeleton is male or female, you have to estimate the ancestry. A "masculine" trait in one ethnic group is often a "feminine" trait in another. Context is the only thing that prevents errors.

5. Look for "Parturition Scars"

While controversial and not 100% proven, some experts look for "pitting" on the back of the pubic bone (preauricular sulcus). It used to be thought these were caused by childbirth. Now, we know they can just be a feature of a wider female pelvis, but they still serve as a strong "female" indicator regardless of whether the individual actually gave birth.

The human body is a record of a life lived. It is not a textbook illustration. Every time a researcher picks up a femur or a cranium, they aren't just looking for a "skeleton female and male"—they are looking for the story of an individual who defied averages just by existing. Using a combination of the Phenice method for the pelvis and metric analysis for the long bones provides the highest statistical probability of a correct identification, but the expert's greatest tool is the humility to label a specimen "indeterminate" when the bones refuse to speak clearly.