You’re standing in line for coffee. Your phone buzzes in your pocket, and without a single conscious thought, your hand reaches down, flips it over, and checks the screen. Did you decide to do that? Well, yeah, sort of. But you didn't think, Okay, pectoralis major, contract slightly; biceps brachii, flex at thirty degrees. You just did it. This weird gray area between "I meant to do that" and "my body just did it" is why people get so confused about whether skeletal muscles are involuntary or voluntary.

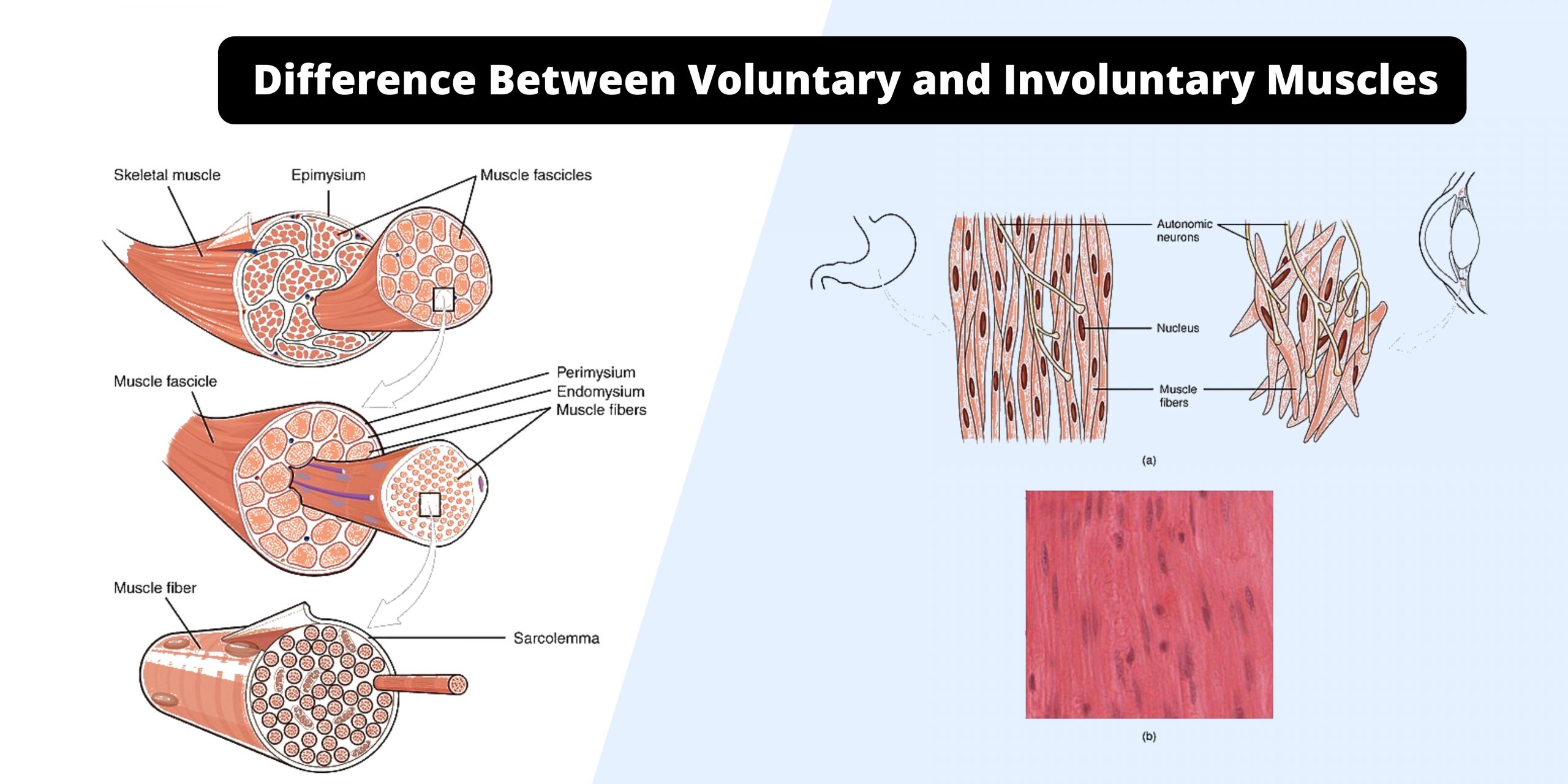

Most textbooks keep it simple. They tell you that cardiac muscle (your heart) and smooth muscle (your gut) are involuntary, while skeletal muscle is voluntary. But that’s a massive oversimplification that ignores how your nervous system actually functions in the real world.

The short answer is that skeletal muscles are technically voluntary because they are controlled by the somatic nervous system. They respond to conscious intent. However, in practice, they spend a huge chunk of their time acting completely on autopilot. If they didn't, you'd collapse into a heap of skin and bone the second you stopped concentrating on your posture.

The "Voluntary" Label and Why It’s Only Half the Story

When we talk about the somatic nervous system, we’re talking about the highway that connects your brain to your muscles via motor neurons. This is the "voluntary" part. You want to pick up a fork? Your primary motor cortex fires off a signal, it travels down the spinal cord, hits the neuromuscular junction, and boom—muscle contraction.

But here’s the kicker.

How many times have you blinked in the last minute? You can control your eyelids. You can squeeze them shut right now if you want to. That makes them voluntary. Yet, you don't spend your day reminding yourself to blink so your eyeballs don't dry out. The diaphragm is another classic example. It’s a skeletal muscle. You can hold your breath, which proves you have voluntary control. But the moment you fall asleep, your brainstem takes over the rhythm. It becomes involuntary by necessity.

📖 Related: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

Life would be a nightmare if every skeletal muscle required 100% of your attention. Imagine trying to hold a conversation while manually calculating the tension needed in your calves, hamstrings, and core just to stay upright. You'd be exhausted in minutes.

The Reflex Loop: When Your Brain Gets Skipped

If you accidentally touch a red-hot stove burner, your hand pulls back before you even feel the pain. This is the withdrawal reflex. In this specific moment, your skeletal muscles are acting entirely involuntarily.

The signal doesn't even go to your brain first. It hits the spinal cord and immediately triggers a motor response to save your skin. Scientists call this a reflex arc. Even though the muscle involved is a "voluntary" skeletal muscle, the action itself was anything but a choice. It’s a hardwired survival mechanism.

This nuance is why the "voluntary" tag is a bit of a misnomer in clinical settings. We have the capacity for volition, but we aren't always using it.

Muscle Fiber Types and the Control Paradox

Not all skeletal muscles are built for the same kind of "voluntary" work. You’ve got Type I (slow-twitch) and Type II (fast-twitch) fibers.

👉 See also: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

- Type I fibers are your marathon runners. They are packed with mitochondria and are incredibly resistant to fatigue. These are the muscles that keep your spine straight. They operate mostly in the background, governed by subconscious postural reflexes.

- Type II fibers are for sprinting or lifting a heavy box. These are the ones we usually associate with voluntary action because we feel the effort of using them.

Think about "muscle memory." When a pro golfer swings a club, they aren't thinking about the 50+ skeletal muscles involved. If they did, they’d probably mess up the shot—a phenomenon called "paralysis by analysis." They’ve trained those voluntary muscles to behave like involuntary ones through sheer repetition. The cerebellum stores these patterns so the conscious mind can stay out of the way.

What Happens When Control Is Lost?

We see the true nature of skeletal muscle control when things go wrong. Take muscle fasciculations—those annoying little twitches in your eyelid or thumb. You aren't doing that. Your brain isn't asking for it. It’s an involuntary discharge of a motor neuron.

Then there are more serious conditions like spasticity in cerebral palsy or multiple sclerosis. In these cases, skeletal muscles contract because the inhibitory signals from the brain are blocked. The muscles are "voluntary" by design, but they are trapped in an involuntary state of tension. It’s a vivid reminder that our control over our own bodies is a delicate balance of "on" and "off" switches that we mostly take for granted.

The Diaphragm: The Ultimate Rule-Breaker

If you want to win an argument about whether skeletal muscles are involuntary or voluntary, bring up the diaphragm. It is the bridge between the two worlds.

It’s histologically a skeletal muscle. It has the striations. It has the receptors. But it is governed by the autonomic-like pacing of the medulla oblongata. It’s the only muscle in your body that is absolutely essential for life on a minute-to-minute basis and yet sits perfectly on the fence of the voluntary/involuntary divide.

✨ Don't miss: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

When you sing, you are exercising voluntary control over it to manage your breath. When you’re in deep REM sleep, it’s running on its own internal clock. It’s a hybrid. Honestly, most of our skeletal system operates on this sliding scale rather than a binary "yes/no" switch.

Why This Distinction Actually Matters for Your Health

Understanding that skeletal muscles operate on a spectrum of control isn't just for biology nerds. It has real-world implications for how you move and heal.

If you have chronic back pain, it’s often because your "involuntary" postural control has gone haywire. Your muscles are staying "on" when they should be "off," or vice versa. Physical therapy is basically a process of using voluntary conscious movement to retrain involuntary subconscious patterns. You are hacking your own nervous system.

Next Steps for Better Movement:

- Check your "background" tension. Periodically throughout the day, scan your body. Are your shoulders up by your ears? Is your jaw clenched? These are voluntary muscles acting involuntarily due to stress. Consciously releasing them resets the feedback loop.

- Train for "automaticity." If you're learning a new sport or lift, do the movement slowly and perfectly. You are trying to move the control of those skeletal muscles from the prefrontal cortex to the cerebellum.

- Breathwork. Since the diaphragm is the one skeletal muscle you can easily control that also links to the autonomic nervous system, using it consciously (deep belly breathing) is the fastest way to flip your body from a "stressed" state to a "relaxed" state.

Basically, your skeletal muscles are a high-tech tool. You have the manual override (voluntary), but for the most part, you’re better off letting the software (involuntary reflexes) handle the day-to-day operations. Just make sure the software isn't running "clench_shoulders.exe" in the background 24/7.