Space is big. Really big. You’ve probably heard that before, but honestly, our brains aren't exactly wired to grasp the sheer, staggering vastness of the solar system, especially when we try to visualize the size order of planets on a single screen or a poster. Most of those classroom diagrams you grew up with? Total lies. They show the planets lined up like marbles on a shelf, sitting right next to each other. In reality, if Earth were the size of a cherry tomato, Neptune would be blocks away, and Jupiter would be a giant watermelon at the end of the street.

The scale is just broken.

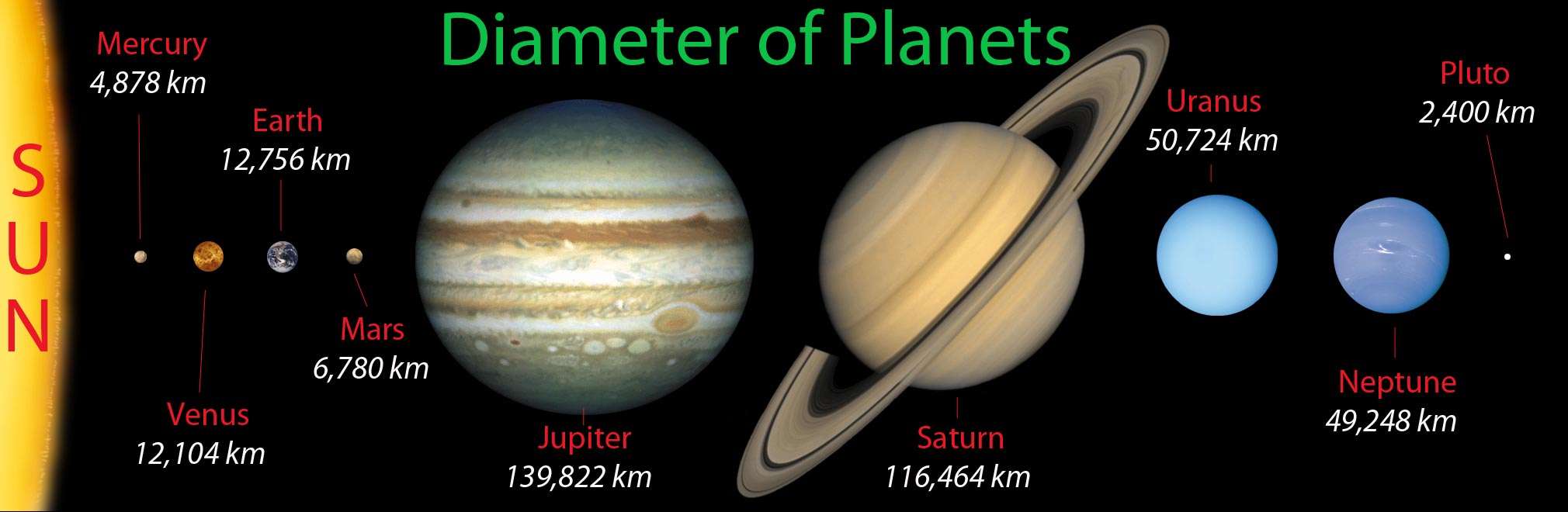

When we talk about the size order of planets, we’re looking at a range of worlds that vary from tiny, scorched rocks to gas giants so massive they could swallow Earth a thousand times over. It’s a hierarchy that tells a story about how our solar system formed—basically a messy, high-speed collision of dust and gas that happened billions of years ago.

Ranking the solar system from biggest to smallest

Jupiter is the undisputed king. It’s huge. It’s so massive that it contains more than twice the mass of all the other planets combined. If you want to get technical, its mean radius is about 43,441 miles (69,911 kilometers). Basically, if you were trying to fill it up like a jar of marbles, you’d need about 1,300 Earths to fill the volume of just one Jupiter. It’s a gas giant that almost became a star, but it just didn't quite have the "oomph" to kickstart nuclear fusion.

Next up is Saturn. Everyone loves the rings, but the planet itself is a monster. It’s the second-largest, with a radius of roughly 36,184 miles. Interestingly, Saturn is the least dense planet in the system; it’s actually less dense than water. If you had a bathtub big enough—which you don't, obviously—Saturn would float.

Then we hit the "ice giants," Uranus and Neptune. They look sort of similar at first glance, but they aren't twins. Uranus is actually slightly larger in terms of physical diameter, coming in third with a radius of 15,759 miles. However, Neptune—the fourth largest by size—is actually more massive. It's denser. It’s got more "stuff" packed into a slightly smaller ball. It’s a weird quirk of planetary science that size and mass don't always move in lockstep.

👉 See also: Why the US Army Stryker Vehicle Still Matters (and What Everyone Gets Wrong)

The rocky inner circle

Then there’s a massive drop-off. We move from the giants to the terrestrial planets, and the scale change is jarring.

- Earth: Our home is the largest of the rocky planets. It’s about 3,959 miles in radius.

- Venus: Often called Earth’s twin because it’s nearly the same size (about 95% of Earth's diameter), but it’s a hellish landscape of sulfuric acid clouds and crushing pressure.

- Mars: The Red Planet is actually much smaller than people realize. It’s roughly half the size of Earth. Think of it as the "small" sibling.

- Mercury: The tiny, cratered world closest to the sun. It’s barely larger than our Moon.

Why the size order of planets matters for gravity

Size isn't just a number on a chart; it dictates everything about a planet's "personality." The bigger the planet, the more gravity it has. Jupiter’s gravity is so intense it acts as a cosmic vacuum cleaner, sucking up stray asteroids and comets that might otherwise go careening into the inner solar system and hitting us. We basically owe our lives to Jupiter’s bulk.

On the flip side, Mercury is so small it can't even hold onto a proper atmosphere. The solar wind just strips it away. Gravity is the glue of the universe, and in the size order of planets, it’s the heavyweights that call the shots.

NASA’s Juno mission has been giving us incredible data about Jupiter’s interior, suggesting that its "core" might not even be a solid rock, but a fuzzy, diluted region of metallic hydrogen. This changes how we calculate the actual "size" of the planet’s structural layers. When you're dealing with gas giants, where the "surface" ends and the atmosphere begins is always a bit of a moving target.

The Pluto debate that won't die

We have to talk about Pluto. It was the ninth planet when most of us were in school. Then, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted it to "dwarf planet" status. Why? Because it’s tiny. It’s smaller than the Moon. It’s even smaller than some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

If we included Pluto in the main size order of planets, it would be at the very bottom, looking like a speck compared to Neptune. The discovery of Eris—another object in the Kuiper Belt that appeared to be more massive than Pluto—is what really killed Pluto's planetary status. Astronomers realized that if Pluto stayed a planet, they’d have to add dozens of other "ice balls" to the list. They chose to trim the list instead.

Visualizing the scale (The fruit analogy)

To really wrap your head around the size order of planets, try this mental exercise. It’s the most common way astronomers explain it to non-science folks.

- Jupiter is a large watermelon.

- Saturn is a large grapefruit.

- Uranus is an orange.

- Neptune is a lime.

- Earth and Venus are two little cherry tomatoes.

- Mars is a blueberry.

- Mercury is a single peppercorn.

Now, imagine the Sun. In this same scale, the Sun isn't a fruit. It’s a giant inflatable ball that would fill the entire back of a pickup truck. The difference between the Sun and the planets is even more extreme than the difference between Jupiter and Mercury.

What we get wrong about planetary distances

Size is one thing, but distance is where our mental models really fail. If you look at a textbook, the planets are usually shown bunched up together. If they were actually that close, the gravity of Jupiter would tear Earth out of its orbit in a heartbeat.

🔗 Read more: AOL App for iPhone: Why This 90s Relic Still Beats Modern Mail

The distance between the planets is mostly... nothing. Just empty, freezing vacuum.

If you used the "watermelon" scale for Jupiter, the distance from the Sun to the Earth would be about 100 yards—the length of a football field. Neptune would be over two miles away. Space is mostly just space. That’s why we call it that.

The future of planetary measurement

We are getting better at measuring these things every year. With the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), we aren't just looking at the size order of planets in our own backyard; we’re looking at exoplanets in other star systems. We’ve found "Super-Earths" and "Mini-Neptunes"—sizes that don't even exist in our own solar system.

It turns out our solar system is a bit of an oddball. Many other systems have huge planets sitting very close to their stars. We have small rocky ones near the heat and big gassy ones in the cold. It’s a neat, orderly arrangement that might be rarer than we thought.

Actionable insights for space enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into how these sizes affect what you see in the night sky, here is what you can actually do:

- Download a scale app: Use an app like "Solar Walk" or "SkySafari." They let you zoom in and out to see the real-time distance and size relationships without the distortion of a paper map.

- Visit a "Scale Model" trail: Many cities have built "Solar System Walks" where the planets are placed at their relative distances. Walking from the Sun to Pluto is a humbling experience for your legs and your brain.

- Check the mass vs. volume: Next time you look at a planet chart, look for "Mass." You’ll notice Neptune is "heavier" than Uranus even though it's "smaller." That’s the key to understanding planetary density.

- Watch the transits: When Mercury or Venus passes in front of the Sun (a transit), look at the photos from NASA. Seeing that tiny black dot against the massive solar disk is the only way to truly feel the scale of our neighborhood.

Understanding the size order of planets isn't just about memorizing a list. It’s about realizing how small our "big" world actually is. Earth is a beautiful, fragile cherry tomato floating in a very, very large dark room.

📖 Related: Cómo descargar videos sin marca de agua sin perder la cabeza (ni la calidad)

The next time you look up at a bright "star" that turns out to be Jupiter, remember that you’re looking at a world so large it doesn't even make sense. It’s out there, spinning at incredible speeds, holding the rest of us together.