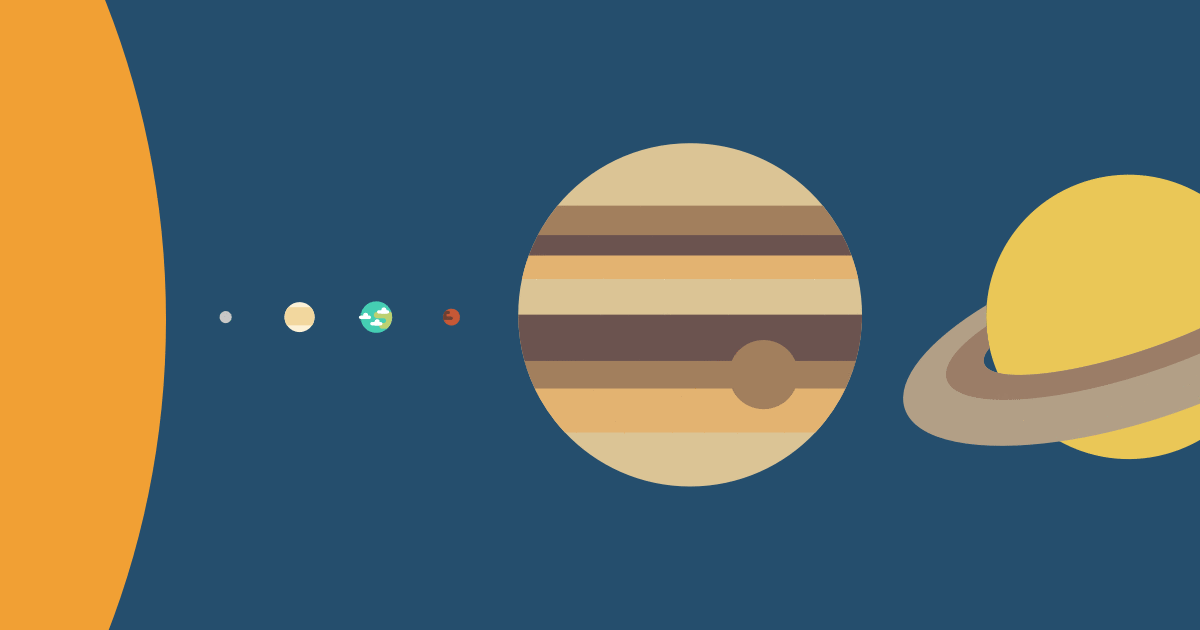

Space is big. Really big. But honestly, most of those posters you saw in elementary school are lying to you. They show the planets lined up like a neat row of marbles, all roughly the same size, sitting just a few inches apart. That is not even close to reality. If you want to talk about the size of all planets, you have to start by throwing out the idea of a "typical" world.

There are no typical worlds here.

We live on a rock that feels huge when you're stuck in traffic, but in the grand scheme of the solar system, Earth is basically a speck of dust. Then you’ve got Jupiter, a monster so massive it doesn't even orbit the center of the Sun—it orbits a point just outside the Sun's surface. It’s a chaotic, mismatched family of giants and runts.

The inner circle of rocky runts

Let's look at the neighborhood we live in. The terrestrial planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—are the small fry. They are made of rock and metal, and they are tiny.

Mercury is the smallest of the bunch. It is barely bigger than our Moon. With a diameter of about 4,879 kilometers, it’s a shriveled, cratered little ball that's actually shrinking. Because its core is cooling, the whole planet is physically contracting. Think about that for a second. It's a world that is getting smaller as we speak.

Venus is Earth's "twin," but only if your twin is a hellish nightmare of sulfuric acid. In terms of the size of all planets, Venus and Earth are the most similar. Venus has a diameter of 12,104 km, while Earth sits at 12,756 km. It’s almost a match. But the similarity ends at the surface. Earth is the goldilocks zone winner, while Venus is a runaway greenhouse effect.

Then there’s Mars. People often think Mars is big because we talk about colonizing it so much. It's not. Mars is small. It’s only about half the size of Earth, with a diameter of 6,779 km. If you stood on Mars, you'd feel much lighter because there’s just less stuff under your feet pulling you down.

The gas giants are playing a different game

Once you cross the asteroid belt, the scale breaks. You aren't just looking at bigger planets; you're looking at a completely different category of existence.

💡 You might also like: How to Convert Kilograms to Milligrams Without Making a Mess of the Math

Jupiter is the king. Period. Its diameter is a staggering 139,820 km. You could fit about 1,300 Earths inside Jupiter. If Earth were the size of a nickel, Jupiter would be the size of a basketball. It’s mostly hydrogen and helium, swirling in a violent dance that has lasted billions of years. When people research the size of all planets, Jupiter is usually the one that makes them rethink their place in the universe. NASA's Juno mission has shown us that its "surface" isn't even a surface—it's just gas getting thicker and thicker until it becomes a weird, metallic liquid.

Saturn comes next. Everyone loves the rings, but the planet itself is a beast. It’s about 116,460 km across. Saturn is huge, but it's surprisingly light. It’s the only planet in our solar system that is less dense than water. If you had a bathtub big enough, Saturn would float. Imagine a giant, ringed beach ball.

The ice giants and the blue mystery

Uranus and Neptune are often lumped together, but they have their own distinct personalities. Uranus has a diameter of 50,724 km, making it significantly larger than Earth but a puny cousin to Jupiter. It’s famous for being tilted on its side. It basically rolls around the Sun like a bowling ball.

Neptune is slightly smaller in diameter than Uranus (49,244 km) but it is actually more massive. It's denser. It’s a heavy, compact ball of ice, ammonia, and methane. The winds there are the fastest in the solar system, screaming across the blue clouds at speeds that would shred a steel building.

Putting the scale into perspective

It is one thing to read numbers. It is another to feel them.

Let's try a mental exercise. If the Sun were the size of a typical front door, Earth would be the size of a nickel. Jupiter would be about the size of a basketball. And Pluto? If we still counted Pluto as a primary planet (which the IAU stopped doing in 2006, much to the heartbreak of 90s kids), it would be the size of a popcorn kernel.

When we discuss the size of all planets, we have to mention the "Barycenter." This is the center of mass of every object in the solar system. Because Jupiter is so incredibly large, the center of gravity between it and the Sun actually lies outside the Sun's physical body. They are essentially dancing around each other in a way no other planet can manage.

📖 Related: Amazon Fire HD 8 Kindle Features and Why Your Tablet Choice Actually Matters

The outliers: Why Pluto lost its spot

Poor Pluto. It was discovered by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930 and sat on our maps for decades. But as our telescopes got better, we realized Pluto was a bit of an impostor. It’s tiny—only about 2,376 km wide. That’s smaller than our Moon.

The real kicker came when Mike Brown and his team at Caltech found Eris in 2005. Eris was around the same size as Pluto. This forced astronomers to make a choice: either we had hundreds of planets we hadn't named yet, or we needed a better definition. They chose the latter. To be a "planet," you have to clear your neighborhood of other debris. Pluto lives in the Kuiper Belt, a messy junkyard of ice, so it got demoted to "dwarf planet."

How do we actually measure these things?

You can't exactly pull out a tape measure in a vacuum. Scientists use several methods to determine the size of all planets with terrifying precision.

- Occultation: This is when a planet passes in front of a distant star. By timing how long the star's light is blocked, astronomers can calculate the planet's diameter. It’s like watching a shadow pass over a flashlight.

- Spacecraft Transit: When we send probes like Cassini to Saturn or New Horizons to Pluto, we get "ground truth." We can take direct measurements and high-resolution photos that confirm our earthbound math.

- Radar Mapping: For closer neighbors like Venus, we bounce radio waves off the surface. The time it takes for the signal to return tells us the distance and the curvature of the sphere.

The volume vs. mass trap

Don't confuse size with weight.

Saturn is the perfect example. It is the second-largest planet by volume, but it’s a featherweight. Neptune is smaller than Uranus but weighs more. When you're looking at the size of all planets, always check if you're talking about how much space they take up (volume) or how much "stuff" is inside them (mass).

| Planet | Diameter (km) | Relative to Earth |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 4,879 | 0.38x |

| Venus | 12,104 | 0.95x |

| Earth | 12,756 | 1x |

| Mars | 6,779 | 0.53x |

| Jupiter | 139,820 | 11x |

| Saturn | 116,460 | 9x |

| Uranus | 50,724 | 4x |

| Neptune | 49,244 | 3.9x |

Note: The table above uses mean diameters. Because planets spin, they actually bulge at the middle, making them "oblate spheroids" rather than perfect circles.

What this means for our search for life

Understanding the size of all planets isn't just a trivia game. It tells us where we might actually be able to live.

👉 See also: How I Fooled the Internet in 7 Days: The Reality of Viral Deception

If a planet is too small, like Mars, it might not have enough gravity to hold onto a thick atmosphere long-term. If it's too big, like Jupiter, the pressure becomes so intense that "landing" is impossible. You'd just sink into the gas until you were crushed into a diamond-sized pebble.

We are looking for "Super-Earths" in other star systems—planets that are maybe 1.5 to 2 times the size of our home. They seem to be the sweet spot. But in our own backyard, Earth is the only one that got the memo.

Practical steps for space enthusiasts

If you want to wrap your head around these scales without a PhD, there are a few things you can do right now.

Build a toilet paper model. It sounds silly, but it works. If one square of toilet paper represents 10 million miles, the distances and sizes become shockingly clear. You'll run out of paper long before you reach Neptune.

Use a digital orrery. Websites like "Eyes on the Solar System" by NASA allow you to toggle between real-time scales and "readable" scales. Seeing the size of all planets in motion changes how you view the night sky.

Look through a telescope. Even a cheap 70mm refractor will show you Jupiter. You won't see individual clouds, but you will see the disc. Seeing that tiny circle of light—knowing it is 11 times wider than the world you're standing on—is a perspective shift you can't get from a book.

The universe doesn't care about our need for symmetry. It’s lopsided, weirdly scaled, and mostly empty. But knowing that Mercury is a shrinking rock and Jupiter is a gas giant that could swallow us whole makes our little blue marble feel a whole lot more special.

To continue your journey into the cosmos, your next move is to check the current visibility of the gas giants. Jupiter and Saturn are often visible to the naked eye even in light-polluted cities. Download a star-chart app like SkyView or Stellarium, head outside tonight, and find the brightest "star" in the sky. Chances are, you're looking at the biggest object for billions of miles.