History is messy. Usually, the names we remember are the ones attached to the big, flashy battles or the massive, world-altering treaties signed in gold ink. But then you have guys like Sir Charles William Somerset Marling. He wasn’t a general leading a charge. He was a career diplomat—a "Mandarin" in the old-school British sense—who spent his life navigating the collapsing ruins of the Ottoman Empire and the chaotic birth of modern Iran.

Most people have never heard of him. That's a mistake.

If you want to understand why the Middle East looks the way it does today, or how Britain managed to keep its grip on global oil for so long, you have to look at the people in the rooms where it happened. Marling was in those rooms. From Tehran to Copenhagen, he was the guy the Foreign Office sent when things were getting "kinda" complicated. He lived a life of high-stakes poker where the chips were entire nations.

The Early Days and the Rise of a Diplomat

Charles Marling wasn't exactly a self-made man in the way we think of it now. He was born in 1862 into a family with some serious status. His father was Sir William Marling, a baronet. Basically, he was born into the upper crust of Victorian society. This meant he had the right education and the right connections. He went to Clifton College and then Trinity College, Cambridge.

He entered the Diplomatic Service in 1888.

Back then, being a diplomat wasn't just about attending cocktail parties. It was grueling. You traveled by horse, carriage, and steamship. You dealt with diseases that don't exist anymore in the West. Marling’s early career saw him bouncing around from Madrid to Sofia, and then to Tokyo. It was a whirlwind. He was learning the trade—how to read people, how to nudge a government without looking like you're pushing, and how to maintain the "stiff upper lip" when everything around you is going to hell.

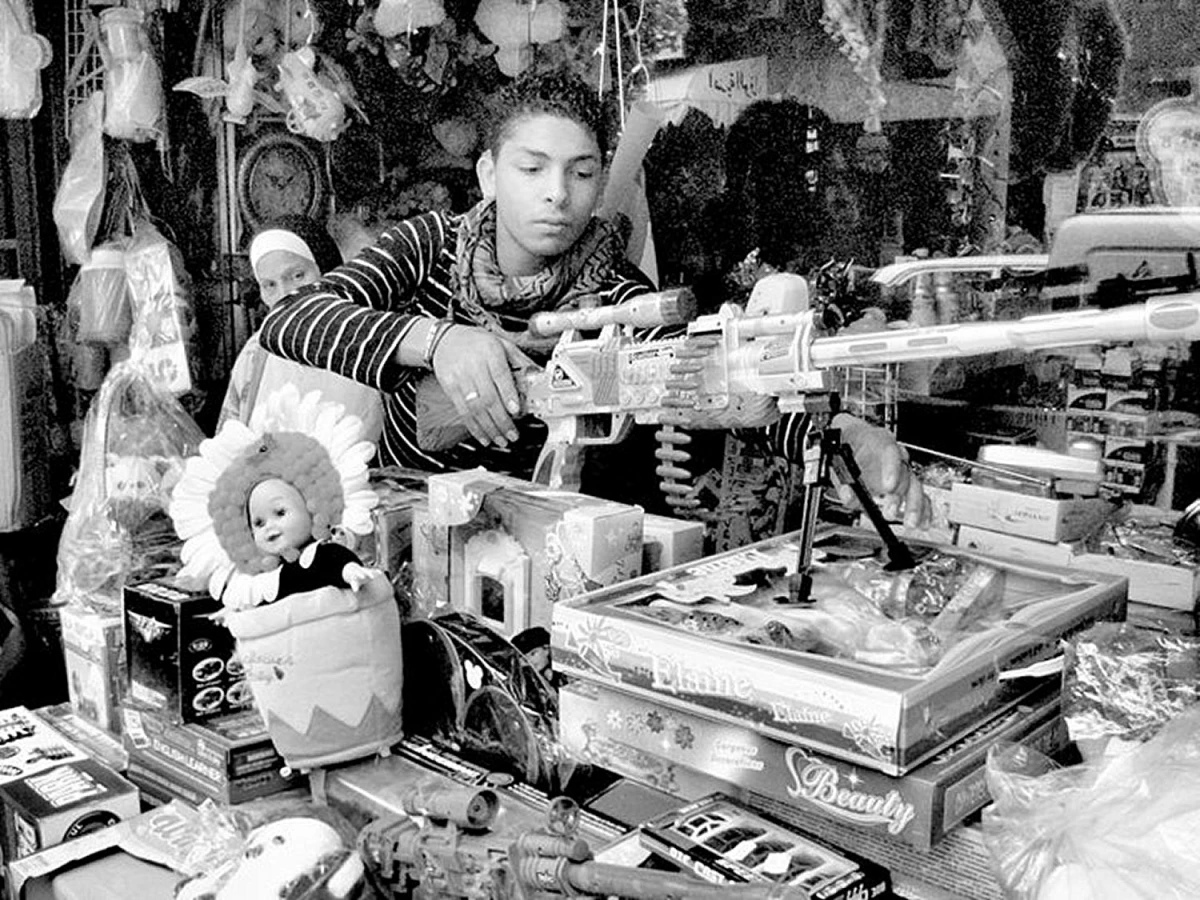

By the time he got to Tehran in 1901 as the Secretary of the Legation, he was already a seasoned pro. Iran (or Persia, as it was called then) was the ultimate "Great Game" playground. On one side, you had the Russians coming down from the north. On the other, the British were pushing up from the south to protect India. Marling was right in the middle of this imperial squeeze play.

The Tehran Years: Revolution and Oil

The period between 1905 and 1915 was arguably the most intense of Marling's career. He was in Tehran during the Persian Constitutional Revolution. Imagine trying to explain Western-style democracy to a country that had been a monarchy for thousands of years, all while your own government is secretly cutting deals with Russia to carve the place up.

📖 Related: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

It was a nightmare.

Marling had to balance the British desire for "stability" (which usually meant keeping the Shah in power) with the reality that the Persian people wanted a say in their own lives. He wasn't always the hero of the story. Diplomats rarely are. Their job is interest, not idealism. He served as the British Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Persia from 1915 to 1918. Those were the war years.

World War I changed everything.

While the trenches were being dug in France, Marling was fighting a different kind of war in Iran. The Germans were trying to stir up tribal revolts to threaten British oil supplies and the route to India. Marling had to play a brutal game of subsidizing local khans, managing the Anglo-Persian Oil Company's interests, and keeping the Persian government from collapsing into total anarchy. Honestly, the fact that the British didn't lose control of the oil fields during this period is largely due to the groundwork Marling laid.

He was knighted for it. In 1916, he became Sir Charles Marling, a KCMG (Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George).

Beyond the Middle East: Denmark and the Later Career

After the dust settled from the Great War, Marling was moved to Denmark. In 1919, he became the British Minister in Copenhagen. You might think that going from the chaos of revolutionary Tehran to the quiet streets of Denmark would be a vacation. It wasn't.

Europe was a wreck.

👉 See also: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

Denmark was the gateway to the Baltic and a crucial point for observing the fallout of the Russian Revolution. Marling spent his time dealing with the repatriation of prisoners of war and the shifting borders of Northern Europe. He was the steady hand. He stayed there until 1926, which is a long stint in the diplomatic world. It shows how much the Foreign Office trusted his judgment.

He eventually moved on to the Netherlands, serving as the Minister at The Hague from 1926 to 1928. He retired shortly after. He died in 1933, just as the world he helped build was starting to fracture again under the weight of a new global tension.

Why Should We Care About Sir Charles Marling Now?

You’re probably wondering why a Victorian-era diplomat matters in the 2020s. It’s a fair question.

The reality is that Marling was one of the architects of the "Informal Empire." This was a system where Britain didn't necessarily own a country, but they controlled its economy, its resources, and its foreign policy through guys like him. When you look at the modern geopolitical struggles over oil in the Persian Gulf or the complex relationship between Iran and the West, you are looking at the echoes of Marling’s work.

He was there for the birth of the oil industry.

He was there for the first Iranian attempts at a parliament.

He was there when the map of the Middle East was being drawn with a ruler and a pencil.

We often talk about history in terms of "Great Men" or "Social Forces." Marling represents the middle ground: the bureaucratic force. He was the instrument of policy. If the policy was flawed—and often it was—it was Marling who had to make it work on the ground. He had to be a psychologist, a spy, a lawyer, and a salesman all at once.

What People Get Wrong About Late-Victorian Diplomacy

There’s this idea that these guys were all arrogant imperialists who didn't care about the local culture. That's a bit of a caricature. Marling, like many of his contemporaries, actually had a deep, albeit patronizing, interest in the places he lived. You can't navigate a revolution in Tehran without understanding the nuances of Persian power dynamics.

✨ Don't miss: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

He was deeply aware of how fragile British power actually was.

His private correspondence—and the official dispatches he sent back to London—reveal a man who was often frustrated by the lack of clear direction from his bosses in the Foreign Office. He frequently warned that the British were overextending themselves. He saw the rise of nationalism long before the politicians in London took it seriously.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Life of Marling

If we look at Sir Charles Marling's career as a case study in high-level negotiation and geopolitical management, there are a few things we can actually apply today, whether you're in business or international relations.

- Understand the "Third Party" Dynamics: Marling rarely just dealt with Britain and Persia. He was always calculating what Russia, Germany, or the local tribes would do. In any negotiation, the people not at the table are often as important as the ones who are.

- Longevity Matters: Marling spent years in the same region. He didn't just drop in for a six-month "tour." He understood the language, the history, and the grudges. In a world of "quick wins," his career is a reminder that real influence takes decades to build.

- The Power of Informal Influence: Often, Marling achieved more through a private dinner or a quiet conversation with a local official than through formal protests. Influence is rarely about shouting; it's about being the most reliable person in the room.

- Adaptability is Everything: He transitioned from the height of the British Empire's power to its post-WWI decline. He didn't stay stuck in 1890. He adjusted his tactics as the world changed around him.

Sir Charles William Somerset Marling lived through the pivot point of the modern world. He was a man of his time, certainly, but his influence outlived him. Next time you see a headline about tensions in the Straits of Hormuz or diplomatic shifts in Eastern Europe, remember that the foundations for those stories were laid by men like Marling, working in the shadows of history with a pen, a telegram, and a very long memory.

To really get the full picture of this era, check out the archives of the British Foreign Office (FO 248 series) or read "The Strangling of Persia" by Morgan Shuster. Shuster was an American who was actually there at the same time as Marling, and he gives a much more critical view of British and Russian interference. Comparing the two perspectives is the only way to see the truth.

Don't just take the official version of history at face value. Dig into the dispatches. Look at the maps. The past is never as settled as it looks in the textbooks.