Everyone knows the song. That infectious, bouncy melody paired with lyrics about a heartbreak so deep it leaves you "singing the blues." But when most people think of it, they immediately go to Guy Mitchell or maybe the original Guy Mitchell hit from 1956. If you're a real country music nerd, though, you know that singing the blues Marty Robbins style is a completely different beast.

It wasn't just a cover. It was a statement.

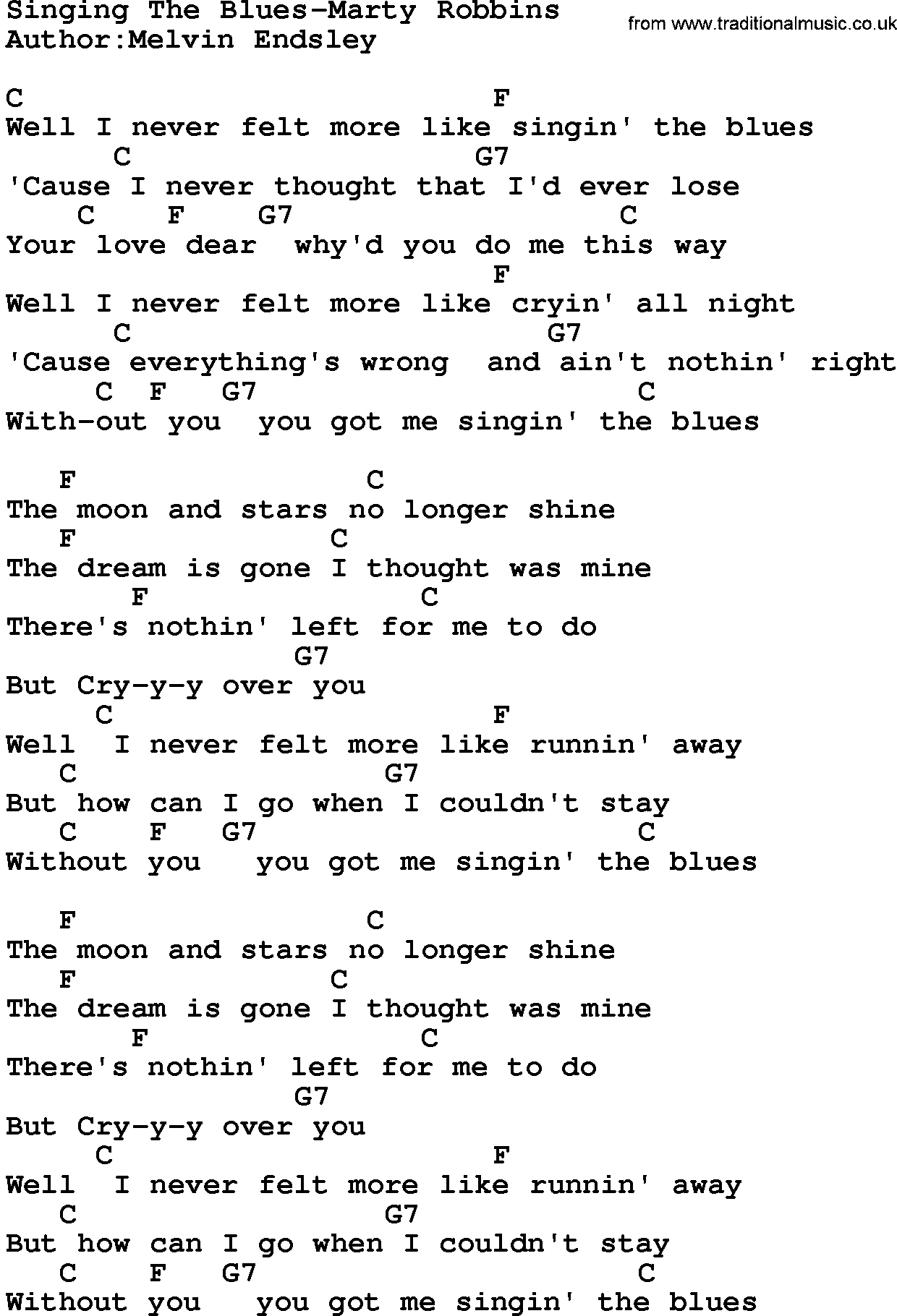

In late 1956, the music world was in a weird spot. Rock and roll was kicking the door down, and traditional country artists were sweating. Marty Robbins, a guy who basically refused to be put in a box, saw this song written by Melvin Endsley and decided he could do something special with it. It worked. His version spent 13 weeks at the top of the country charts. Honestly, it’s one of the few times a song was a massive pop hit and a massive country hit simultaneously by two different artists, with Mitchell owning the pop charts and Robbins dominating the jukeboxes in every honky-tonk from Nashville to Phoenix.

The Endsley Connection and the Birth of a Hit

Melvin Endsley was a kid from Arkansas with a gift for melody and a really tough break in life, having been struck by polio. He wrote "Singing the Blues" while he was still a teenager. Think about that. A kid who could barely move was writing the upbeat anthem of the decade.

Marty Robbins didn't just stumble onto it. He had an ear for hits. When he recorded it for Columbia Records, he wasn't trying to be a rockabilly star, though the song definitely has those "cat" vibes. He was a crooner. He had that smooth, velvety voice that could transition from a whisper to a cry in a single bar.

When you listen to the Marty Robbins version, the first thing you notice is the whistling. It’s iconic. It’s lighthearted, which creates this bizarre, brilliant contrast with the fact that he's singing about wanting to die because his girl left him. That’s the magic of the blues—it’s a "laughing to keep from crying" situation.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Recording

There’s a common misconception that Marty was just chasing Guy Mitchell’s coattails. The timeline is actually much tighter than people realize. Both versions were released around the same time in 1956. While Mitchell’s version had more of that big-band, polished pop sheen, Marty’s version felt rural. It felt like it belonged on a dusty porch.

🔗 Read more: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The instrumentation is worth geeking out over. You’ve got those steady, clicking percussive sounds—likely a mix of muted guitar strings and maybe even a literal woodblock—that give it a "walking" tempo. It’s driving. It’s relentless.

- The Vocals: Marty doesn't oversing. He stays in this cool, detached pocket.

- The Whistle: It wasn't just filler; it became the song’s signature hook.

- The Bass: Notice the walking bassline? That’s what pulled in the rockabilly crowd.

A lot of folks forget that Marty Robbins was a pioneer of "crossover." Before "El Paso" made him the king of the Western ballad, singing the blues Marty Robbins proved he could take a simple pop structure and make it country gold. He was a bridge. He connected the era of Hank Williams to the era of Elvis Presley without losing his soul in the process.

Why the 1956 Charts Were a Battlefield

You have to understand the context of 1956. This was the year of "Heartbreak Hotel." The year "Don't Be Cruel" happened. The traditional Nashville sound was terrified.

Columbia Records was hedging their bets. By having Guy Mitchell take the song to the "Hit Parade" (the pop world) and Marty Robbins take it to the "C&W" charts, they essentially cornered the market. It was a brilliant business move, but it only worked because Marty’s performance was so earnest.

If you compare the two versions side-by-side today, Mitchell sounds a bit like a theatrical production. It’s great, don’t get me wrong. But Robbins? He sounds like he’s actually walking down the street with his hands in his pockets, whistling because he doesn't know what else to do with his grief. It’s more human.

The Technical Brilliance of the "Marty Style"

Marty Robbins had a vocal range that made other singers nervous. He could do the "High Lonesome" sound, but he preferred a mid-range intimacy. In "Singing the Blues," he uses a technique called "the break." It’s that little hitch in the voice that signals emotion.

💡 You might also like: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Unlike some of his later hits where he leaned heavily into the Spanish-influenced "Tex-Mex" sound, this track is pure Americana. It’s stripped down. There are no swelling violins or backing choirs (though he’d use those later). It’s just a man, a guitar, and a rhythm section that sounds like a ticking clock.

It’s actually quite difficult to sing. The timing of the "well-well-well" phrases requires a natural sense of swing that most modern singers struggle to replicate. You can’t teach that kind of phrasing; you either have it or you don't. Marty had it in spades.

Long-Term Impact on Country Music

This song changed the trajectory of Marty’s career. It gave him the leverage to start experimenting. Without the success of this pop-leaning country hit, the suits at the label might never have let him record a five-minute-long story-song about a cowboy in West Texas (the legendary "El Paso").

It also influenced a generation. If you listen to early George Jones or even the way Buck Owens approached his upbeat 60s hits, you can hear the echoes of Marty’s rhythmic delivery. He proved that country music didn't have to be "twangy" in a way that felt dated. It could be sleek. It could be cool.

The Mystery of the Whistle

There’s been some debate over the years about who actually did the whistling on the track. While Marty was a capable whistler, some session logs suggest it might have been a studio pro or even a doubled track to give it that piercing, clean quality. Regardless of who blew the air, it’s the element that sticks in your brain. You can hear the first three notes and you know exactly what song it is. That’s the hallmark of a masterpiece.

How to Appreciate the Song Today

If you’re just getting into Marty Robbins, don’t stop at the "Gunfighter Ballads." You need to dig into these early Columbia sides.

📖 Related: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

- Listen for the "dead-note" guitar picking. It’s a masterclass in rhythm.

- Pay attention to the lyrics. "I never thought I'd miss you so / But boy, I'm finding out that it's true." It’s simple, but the way he lingers on "true" is pure heartbreak.

- Compare it to the covers. Everyone from Dean Martin to Paul McCartney (during the Unplugged era) has touched this song. None of them capture the specific "lonesome-yet-lively" vibe that Robbins nailed.

It’s easy to dismiss old music as "simple." But "Singing the Blues" is a complex piece of emotional architecture. It’s a song about depression disguised as a jaunty stroll. That’s a hard needle to thread.

The Legacy of a Multi-Genre Icon

Marty Robbins went on to become a NASCAR driver, a novelist, and a movie star. But at his core, he was a guy who understood how to sell a song. He wasn't afraid to whistle. He wasn't afraid to sound a little bit "pop" if it meant the song reached more people.

When you look back at the history of the Billboard charts, the 1950s were a chaotic melting pot. Singing the blues Marty Robbins stands out as a moment of perfect clarity. It’s a record that doesn't sound 70 years old. It sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday in a boutique studio in East Nashville.

Practical Steps for the Modern Listener

To truly understand the weight of this recording, you should seek out the original 45rpm mono mix if you can. The stereo re-channels often lose that punchy center where the bass and the whistle live.

- Check out the The Essential Marty Robbins collection. It places "Singing the Blues" in the context of his move from honky-tonk to pop-stardom.

- Watch the old Ozark Jubilee footage. Seeing Marty perform this live (or lip-syncing for TV) shows his charisma. He had this "aw-shucks" grin that made the heartbreak in the lyrics even more poignant.

- Analyze the song structure. It’s a standard AAB structure that repeats, which is why it’s so catchy. It’s designed to be a "brain worm."

The real takeaway here is that Marty Robbins wasn't just a "cowboy singer." He was a vocal stylist who could take a song written by a teenager and turn it into a multi-generational standard. He didn't just sing the blues; he owned them.

Next time you’re feeling a bit down, put this track on. Don't go for the sad, slow ballads first. Go for the whistle. Go for the clicking rhythm. You’ll find that "Singing the Blues" doesn't actually make you feel blue—it makes you feel like someone else has been there, done that, and decided to whistle their way through it anyway. That’s the Marty Robbins way.