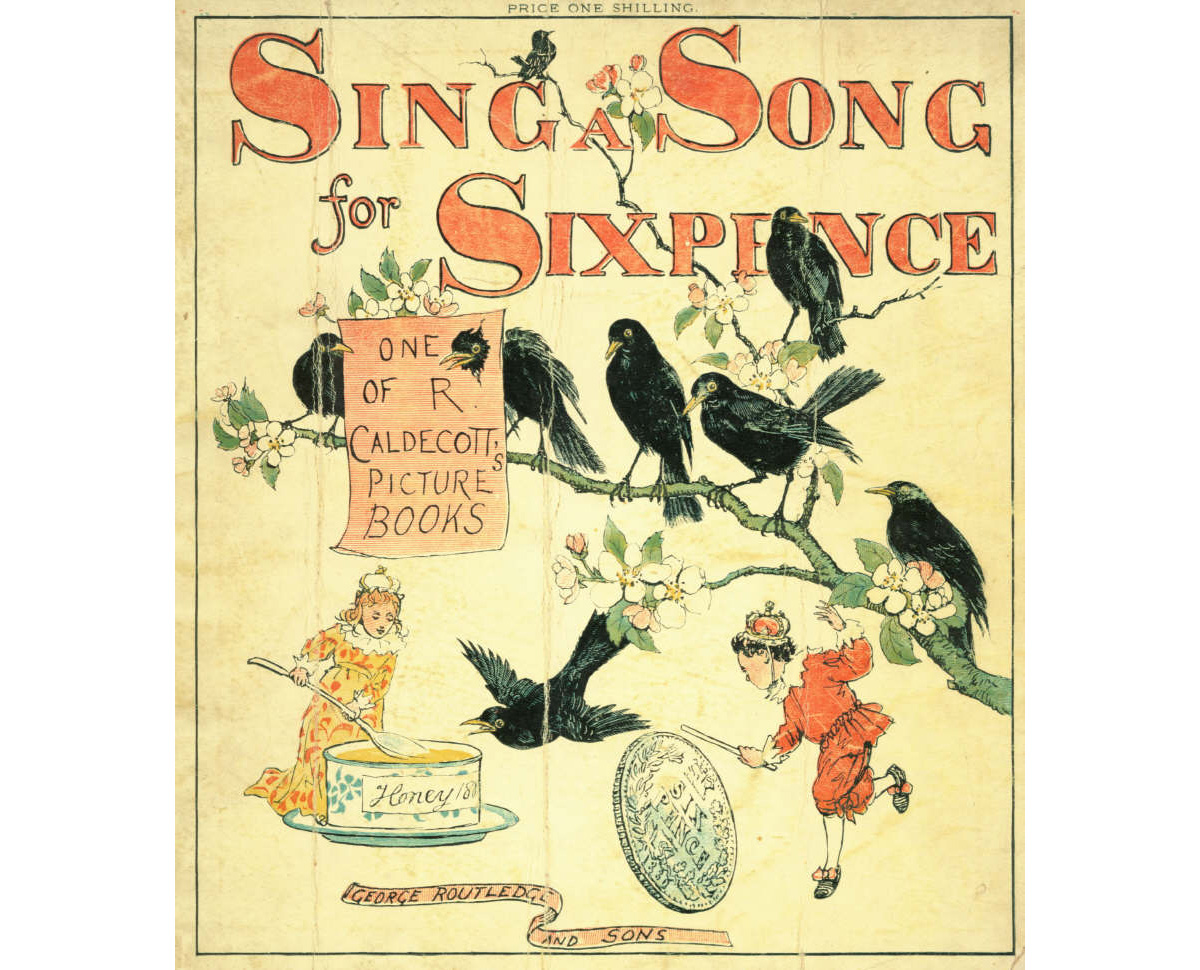

You probably know the tune. It’s one of those nursery rhymes that’s so deeply embedded in our collective childhood that we rarely stop to ask why on earth someone is baking live birds into a crust. It sounds like a fever dream. A king in his counting house, a queen eating honey, and a maid getting her nose nipped off by a vengeful avian survivor. But Sing a Song of Sixpence isn't just a nonsensical jingle to keep toddlers quiet. It’s a weirdly accurate window into Renaissance culinary flexes, 18th-century printing wars, and some truly wild (if debunked) political conspiracy theories.

Honestly, the imagery is kind of metal.

The rhyme we recognize today started stabilizing in the mid-1700s, but its roots go back way further. Most scholars point to Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (around 1602), where Sir Toby Belch mentions "a song of sixpence." Was he talking about the same song? Maybe. Or maybe "sixpence" was just the "five bucks" of the Elizabethan era—a standard price for a cheap thrill or a quick tune.

What Really Happened with the Blackbirds?

Let’s talk about the pie. It’s the centerpiece of the whole thing. To a modern ear, "four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie" sounds like a recipe for a very crunchy, very feathers-heavy disaster. But here’s the thing: people actually did this.

Not the "killing them and eating them" part—though songbirds were a delicacy—but the "living birds flying out" part.

In the 16th century, Italian chefs were the ultimate showmen. They loved "entremets," which were basically elaborate edible (or non-edible) entertainments served between courses. There is a famous cookbook from 1549 by Christoforo di Messisbugo that actually describes how to make a pie crust, fill it with live birds, and serve it so that when the host cuts the lid, the birds fly out. It was the Renaissance version of a jump scare.

Why blackbirds?

They were common. They were loud. And they provided that "dainty dish" aesthetic for a king who wanted to show off his wealth by wasting a perfectly good pastry on a prank.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The rhyme captures this specific moment of aristocratic excess. You’ve got the King, the Queen, and the Maid—the whole social hierarchy of the manor—reacting to this absurd culinary stunt. It’s basically a 1700s TikTok prank gone wrong.

The Political Gossip and Secret Codes

Humans love a good conspiracy. Because Sing a Song of Sixpence feels so specific, people have spent centuries trying to attach "secret" meanings to it. You’ll hear some folks swear it’s about Henry VIII. In this version:

- The King is Henry (obviously).

- The Queen is Catherine of Aragon.

- The Maid is Anne Boleyn (the "blackbird" who snatches the King’s attention).

- The "sixpence" represents the monasteries Henry dissolved to get his hands on some quick cash.

It’s a fun theory. It really is. But there’s zero historical evidence to back it up. Most folklorists, like the legendary Iona and Peter Opie—who basically wrote the bible on nursery rhymes, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes—argue that these political interpretations were mostly made up by Victorians who were bored and liked over-analyzing things.

Another wild theory claims it’s a coded message for Blackbeard the pirate. The "sixpence" was supposedly the daily wage he offered his crew, and the "twenty-four blackbirds" were his hidden snipers. Again, it’s total fiction. But it speaks to how much this rhyme gets under our skin. We want it to mean something deeper because the literal meaning—birds in a pie—is just too weird to accept at face value.

The Changing Lyrics: A Publishing War

If you look at the earliest printed version in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (circa 1744), the lyrics are slightly different. It wasn’t "sing a song of sixpence," but "Sing a Song of Sixpence, / A bag full of Rye."

Wait, rye?

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Yeah. Some historians think the "rye" was actually a reference to a specific measurement of grain, or perhaps it was just a cheap filler. By the time Mother Goose’s Melody came out in 1780, the "pocket full of rye" became the standard.

And then there’s the maid. In some early versions, she doesn't just get her nose nipped off. She dies. Or, in the "happier" versions added later by sensitive Victorian parents, a little bird comes along and sews her nose back on. This "surgical" ending was a late addition because, apparently, 19th-century kids were getting nightmares about facially disfigured domestic workers.

The Counting House and the Honey

The second verse takes us into the private lives of the royals.

The king was in his counting house, / Counting out his money;

The queen was in the parlour, / Eating bread and honey.

This isn't just filler. It reflects the gender roles of the 18th century. The King is the public figure, dealing with the "business" of the state (the money). The Queen is in the "parlour"—a word derived from the French parler (to speak)—which was a private room for receiving guests and domestic leisure.

Eating bread and honey was a sign of extreme luxury. Sugar was expensive. Honey was the gold standard for sweetness. It paints a picture of a monarchy that is totally disconnected from the reality of the people—while the King counts his gold and the Queen indulges in sweets, the "maid" is outside doing the actual labor (hanging out the clothes) and getting attacked by the King's "entertainment."

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

It’s a subtle, perhaps accidental, commentary on class. The workers take the brunt of the "birds" while the royals enjoy the show and the snacks.

Why It Still Works Today

Nursery rhymes are the ultimate survivors. They survive because they are "sticky." The rhythm of Sing a Song of Sixpence is a trochaic meter, which feels natural and driving. It’s catchy. But more than that, it’s the surrealism.

Kids love the idea of a pie that talks back. They love the "snap" of the blackbird. It’s a bit of mild horror mixed with a catchy beat.

Modern References You Might Have Missed

- Literature: Agatha Christie, the queen of the macabre, used the rhyme as a structural device for her book A Pocket Full of Rye. She loved using nursery rhymes to mask grisly murders.

- Music: Everyone from the Beatles (in "Cry Baby Cry") to jazz legends has referenced the "king in the counting house" imagery. It has become shorthand for "greed" or "isolation in wealth."

Actionable Insights: How to Use This History

If you're a parent, a teacher, or just someone who likes being the smartest person at the pub, here’s how to actually use this info:

- Don't over-sanitize it. Kids actually like the "scary" part where the nose gets nipped. It’s a safe way for them to process the idea of "consequences" or sudden surprises.

- Use it as a history hook. If you’re teaching kids about the Renaissance, use the "live bird pie" fact. It’s 100% true and way more interesting than memorizing dates of battles. The "entremet" tradition shows how much the elite valued spectacle over substance.

- Check your versions. Compare the "nose sewed back on" version with the original. It’s a great jumping-off point for a conversation about how stories change over time to fit what society thinks is "appropriate."

- Look for the "Rye." If you find an old book with the "bag full of rye" lyrics, hold onto it. Those pre-Victorian variations are a window into how oral traditions eventually became "standardized" by the printing press.

Ultimately, Sing a Song of Sixpence is a reminder that the past was a lot weirder than we think. It wasn't all stiff collars and formal portraits; it was also about baking birds into pies just to watch them fly around a dining hall.

Next time you hear the rhyme, don't just think of it as a cute song. Think of it as a 400-year-old receipt for a very expensive, very chaotic dinner party.