Ever looked under your car while the wheels were turned and wondered what’s actually happening? It’s basically a metal stick sliding back and forth. That’s it. That is the magic of the simple rack and pinion diagram in action. It’s a mechanism so old it feels prehistoric, yet without it, you'd probably be crashing your car into a bush every time you tried to navigate a cul-de-sac.

Linear motion is hard. Rotational motion is easy.

Think about it. Motors spin. Engines spin. Our wrists naturally rotate. But most of the work we need done in the physical world happens in a straight line. We need to lift elevators, slide gates, or move a car’s tie rods left and right. The rack and pinion is the "translator" that sits between the spinning world and the straight-line world. It’s the ultimate mechanical handshake.

What Your Simple Rack and Pinion Diagram Is Actually Showing

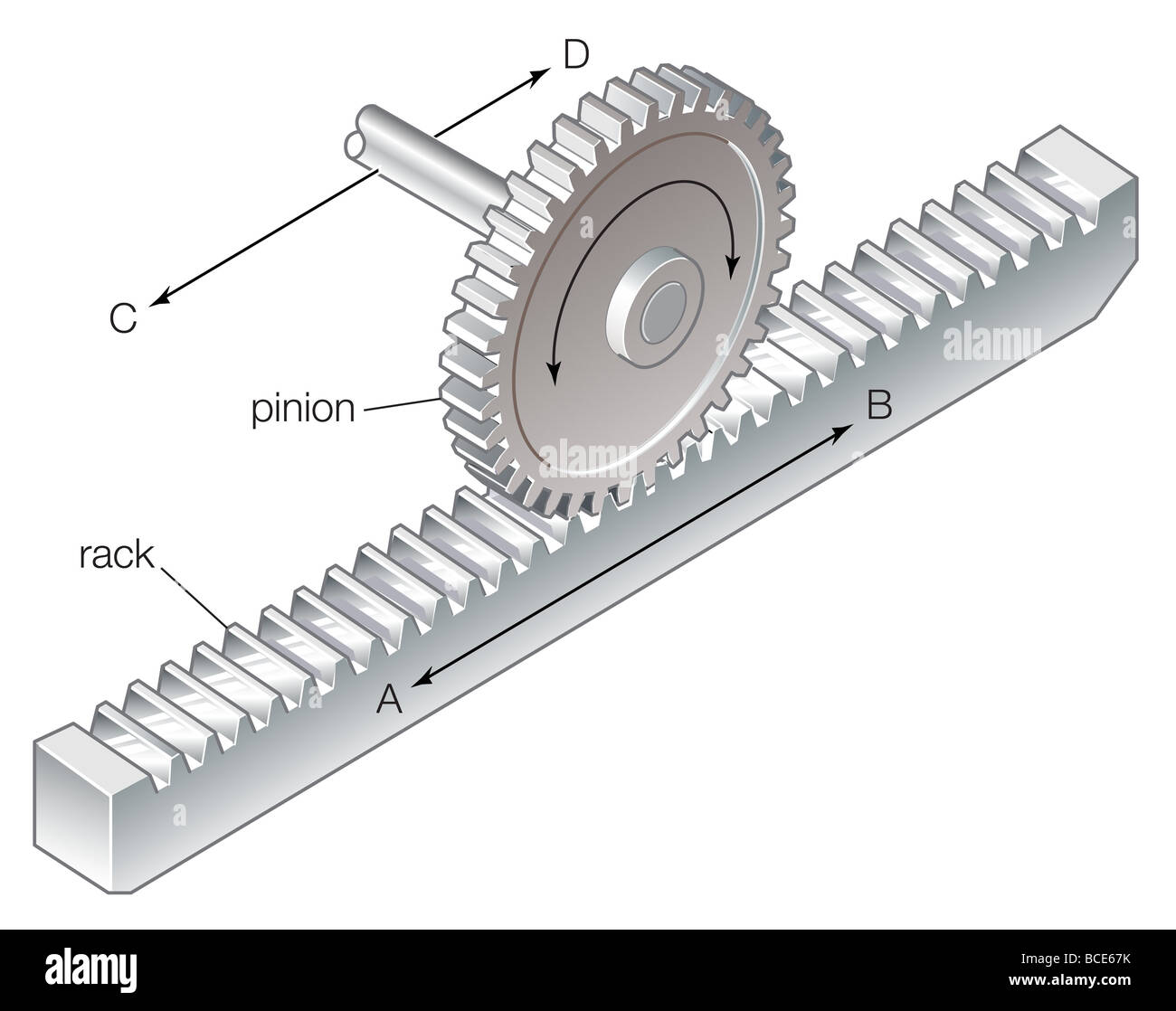

If you pull up a simple rack and pinion diagram, you’re going to see two main players. First, there’s the pinion. This is just a standard circular gear. It’s the "driver." When you turn your steering wheel, you are spinning the pinion. Then there’s the rack. This is essentially a gear that got flattened out by a steamroller. It’s a long, flat bar with teeth cut into one side.

The geometry here is beautiful because it’s constant. In a world of complex variables, the rack and pinion is refreshingly honest. For every single rotation of the pinion, the rack moves a specific, predictable distance.

$$L = \pi \cdot d \cdot n$$

In the formula above, $L$ represents the linear distance the rack travels, $d$ is the pitch diameter of the pinion, and $n$ is the number of revolutions. It’s a 1:1 relationship that doesn't change based on speed or load. Engineers love this. If you know how much you turned the knob, you know exactly where the machine part is. No guessing. No "sorta" or "maybe."

Why We Don't Use Pulsing Hydraulics for Everything

You might ask why we don't just use pistons. Hydraulics are powerful, sure. But they’re messy. They leak. They require pumps and fluid and seals that eventually dry rot and ruin your driveway. A rack and pinion? It’s just metal on metal.

Take the classic 1960s Jaguar E-Type. It was one of the first mainstream cars to really brag about its steering. Why? Because the rack and pinion gave the driver "feel." When the tires hit a pebble, that vibration traveled up the rack, through the pinion, and vibrated the driver's palms. It’s high-fidelity feedback.

Modern "drive-by-wire" systems try to simulate this with little electric vibrating motors, but honestly, it’s not the same. It feels like a video game controller. The raw mechanical connection in a simple rack and pinion diagram is about as "analog" as it gets.

The Problem of Backlash (The Tiny Gap That Ruins Everything)

Nothing is perfect. If you look closely at a high-end simple rack and pinion diagram, you'll notice the teeth don't fit perfectly snug. There has to be a tiny, microscopic gap. This is called backlash.

If the teeth were 100% tight, the friction would generate so much heat that the metal would expand and the whole thing would seize up. But that tiny gap means when you change direction, there’s a split second where the pinion spins but the rack hasn’t moved yet. In a car, you feel this as "dead space" in the steering wheel. In a CNC machine making medical implants, that tiny gap is a disaster.

How do we fix it?

- Helical gears (teeth cut at an angle)

- Split pinions that "spring" against the teeth

- High-tension lubricants

Where You’re Seeing This Right Now (Without Knowing It)

It’s not just cars. If you’ve ever used a drill press in a workshop, you’ve used a rack and pinion. You pull the lever (rotating the pinion), and the drill bit moves down (sliding the rack). It’s in those giant stair-lifts for the elderly. It’s in the mechanism that opens and closes the disc tray on an old DVD player—if you’re old enough to remember those.

Even the world’s most terrifying railways use this.

Look at the Mount Washington Cog Railway. Standard trains use friction. Metal wheels on metal rails. If the hill is too steep, the wheels just spin. To solve this, they put a giant "rack" in the middle of the tracks. The train has a "pinion" gear on its belly. It literally "velcroes" itself to the mountain. It can’t slip. It’s physically impossible for the train to slide down as long as those teeth hold.

Different Flavors of the Same Design

Not all racks are created equal. You’ve got your Straight Rack, which is the cheapest and easiest to make. It’s what you find in toy cars or basic DIY kits. Then you’ve got Helical Racks.

👉 See also: Distance of Jupiter from the Sun: Why It’s Way Further Than You Think

Helical teeth are curved. This allows more surface area of the teeth to touch at once. It’s quieter. It’s smoother. It can handle way more torque. If you're building a heavy-duty industrial robot, you aren't using straight teeth. You’re going helical.

Then there’s the Variable Ratio Rack. This is a clever trick of geometry. In the center of the rack, the teeth are spaced differently than they are at the ends. This means when you’re driving straight on the highway, the steering is "slow" and stable. But when you’re trying to parallel park and you turn the wheel all the way, the ratio changes and the wheels turn much faster. It’s a mechanical way of giving a machine "intelligence" without a single line of code.

The Maintenance Reality

If you’re working with a system based on a simple rack and pinion diagram, your biggest enemy isn't wear—it's dirt.

Because the rack is often exposed (or covered by a rubber boot), any grit that gets into the teeth acts like sandpaper. It grinds down the "involute" profile of the gear teeth. Once that shape is gone, the motion gets jerky.

- Check the boots: If the rubber bellows on your steering rack are cracked, replace them yesterday.

- Grease is life: Use lithium-based greases that won't wash away in the rain.

- Alignment matters: If the pinion isn't perfectly perpendicular to the rack, you’ll get uneven wear that creates "notches" in the movement.

Looking Ahead: Is the Gear Dead?

With the rise of linear motors—where magnets just pull a carriage along a rail—some people think the rack and pinion is headed for the museum. I don't buy it.

Linear motors are expensive. They’re sensitive to magnetic interference. They have zero "holding power" if the electricity goes out. A rack and pinion is cheap, reliable, and it stays where you put it. Even in 2026, as we push toward more automation, the physical connection provided by these gears remains the backbone of heavy industry.

The next time you see a simple rack and pinion diagram, don't just see a school project. See the fundamental bridge between the circular motion of the universe and the linear needs of human life.

Practical Steps for Choosing a Rack and Pinion System

If you are actually looking to implement this in a project—whether it's a DIY CNC router or a gate opener—start with your load requirements. Don't just guess.

First, calculate your Pitch Circle Diameter (PCD). This determines your travel per revolution. A larger pinion moves the rack faster but gives you less mechanical advantage (it's harder to turn). A smaller pinion is "stronger" but slower.

Second, decide on your material. Nylon is great for 3D printers or light loads because it’s "self-lubricating" and quiet. Steel is for when things need to stay put or move heavy weight. If you're using steel, make sure the rack and the pinion have the same Module (the metric measurement of tooth size). If the modules don't match, they won't mesh, and you'll just end up with a pile of metal shavings.

Finally, always build in a way to adjust the "mesh" or the distance between the two. You want them close enough to minimize that backlash we talked about, but not so tight that they bind. Most professional setups use an eccentric mount or a spring-loaded plate to keep the pinion pressed perfectly into the rack's teeth.

Get the geometry right, keep the grit out, and this mechanism will likely outlast the person who installed it.