You’re probably using a lever right now. Or maybe a wedge. You don't think about it because, honestly, who sits around contemplating the physics of their fingernail clippers? But here’s the thing: every complex piece of machinery we have, from the massive cranes building skyscrapers in Dubai to the tiny internal gears of a Rolex, is basically just a mashup of six basic designs. These are the simple machine examples that literally built civilization.

They don't use electricity. They don't have software. They just trade distance for force.

Physics is kinda funny that way. You can’t get something for nothing—that's the law of conservation of energy—but you can definitely cheat the system to make heavy stuff feel light. We call this "mechanical advantage." If you've ever used the back of a hammer to yank a stubborn nail out of a 2x4, you’ve performed a feat of engineering that Archimedes was obsessing over back in the third century BC.

The Lever: Not Just a Seesaw

Most people hear "lever" and think of a playground. Boring. In reality, the lever is the undisputed king of the simple machine examples list because it’s everywhere. It’s your arm. It’s your jaw.

📖 Related: coventchallenge.com expert solutions web development: Why the Open Source Model is Changing Fast

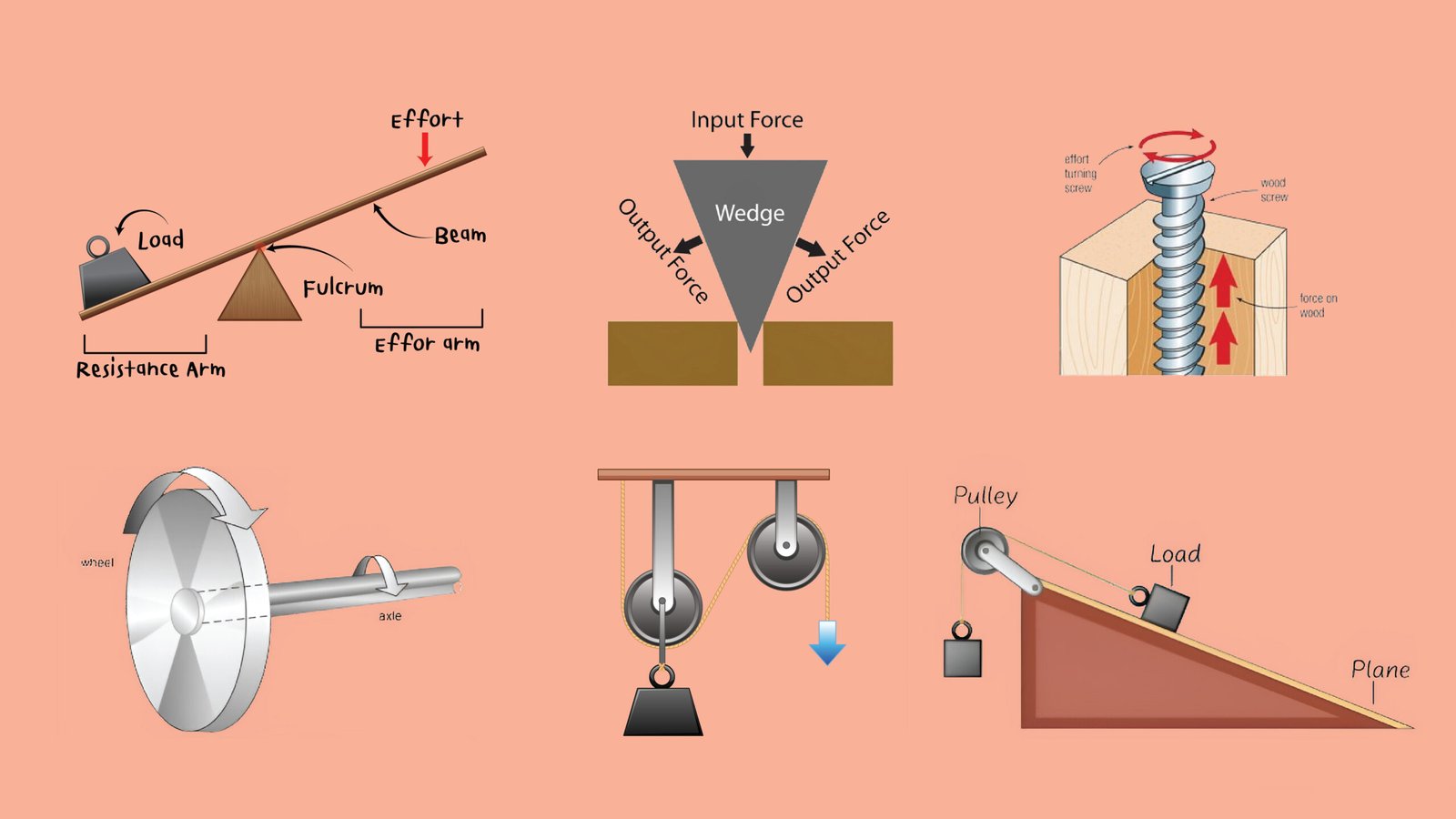

A lever needs three things: a fulcrum (the pivot), a load (the heavy thing), and the effort (you). Depending on where you put those three pieces, you get three different "classes." A pair of scissors is a double Class 1 lever. The pivot is in the middle. When you squeeze the handles, the force travels through the pivot to snip the paper. Simple. But then you look at a wheelbarrow, which is a Class 2 lever. Here, the load is in the middle. Because the wheel acts as the fulcrum at the very end, you can lift 200 pounds of wet mulch without blowing out your lower back.

It’s all about the "moment arm."

Ever tried to open a heavy door by pushing near the hinges? It’s nearly impossible. Push near the handle—the furthest point from the hinge—and it swings right open. That’s the lever principle in action. You’re trading a long, easy movement at the handle for a short, powerful movement at the hinge.

The Pulley is Basically a Lever on a Rope

Pulleys are fascinating because they feel like magic. If you loop a rope over a single fixed wheel, you don't actually get any mechanical advantage. You’re just changing the direction of the force. If you want to lift a 50-pound weight, you still have to pull with 50 pounds of force. It’s just easier to pull down than to lift up because you can use your own body weight to help.

But things get wild when you start adding more pulleys.

This is called a "block and tackle" system. Every time you loop the rope back and forth between the top and bottom pulleys, you distribute the weight. If you have four segments of rope supporting a load, you only need to pull with one-fourth of the force. The catch? You have to pull four times as much rope. To lift a box one foot, you’re pulling four feet of cord.

Sailors on old-school clipper ships used this to move massive sails that weighed tons. Without these simple machine examples, those ships would have stayed in port. Even today, look at the top of any construction crane. You'll see a complex array of cables and wheels. It’s just a fancy version of what the Romans used to build the Colosseum.

The Inclined Plane and the Geometry of the Pyramids

Ramps are low-key the most underrated invention in human history.

Imagine you need to get a 500-pound refrigerator into the back of a moving truck. You have two choices. You can lift it straight up (don't do this) or you can push it up a ramp. The ramp is an inclined plane. By increasing the distance you have to travel, you decrease the effort required.

The Egyptians knew this. There’s a long-standing debate among archaeologists like Mark Lehner and teams from the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology about exactly how the Great Pyramid of Giza was built, but everyone agrees ramps were involved. Whether they were internal spiral ramps or massive external embankments, they used the inclined plane to move 2.5-ton limestone blocks.

Wedges and Screws: The Planes That Move

A wedge is basically just two inclined planes joined back-to-back. But instead of the load moving up the plane, the plane moves into the load. Think of an axe splitting a log. The thin edge enters the wood, and as you drive it deeper, the widening "ramps" of the axe head push the wood fibers apart.

👉 See also: Surface Apple TV: Why Everyone Is Still Waiting for Microsoft and Apple to Finally Kiss and Make Up

Knives, chisels, and even your front teeth are wedges.

Then you have the screw. If you take a long, thin inclined plane (like a paper triangle) and wrap it around a cylinder (like a pencil), you get a screw. The "threads" are just a circular ramp. This allows for immense pressure. When you tighten a bolt, you’re using a tiny amount of rotational force to create a massive amount of linear force. This is why a C-clamp can hold two pieces of steel together so tightly they won't budge.

The Wheel and Axle: Reducing Friction to Zero (Almost)

We take the wheel for granted, but it’s actually a pretty late invention in the grand scheme of things. It showed up around 3500 BC in Mesopotamia.

A wheel and axle is essentially a circular lever. The center of the axle is the fulcrum. When you turn a large steering wheel, you’re applying effort to a long "lever arm" (the radius of the wheel) to turn the smaller axle. This gives you the torque needed to turn the heavy wheels of a car.

But the wheel’s real superpower is friction reduction.

👉 See also: How to switch tabs with keyboard without losing your mind or your flow

Dragging a heavy crate across the floor is hard because the entire surface area of the crate is rubbing against the ground. Put that crate on a cart with wheels, and the only friction is at the tiny point where the axle meets the wheel's hub. Add some ball bearings and a bit of grease, and you’ve basically defeated physics.

Real-World Nuance: Why Efficiency Matters

In a physics textbook, these machines are 100% efficient. In the real world? Not even close.

Friction is the enemy. Every time a rope moves over a pulley or a screw turns into wood, energy is lost as heat. This is why high-end simple machine examples like professional bike gears or industrial winches use specialized materials and lubricants.

- Levers can snap if the material isn't rigid enough.

- Screws can strip if the material is too soft.

- Pulleys can bind if the alignment is off by even a millimeter.

Understanding these limitations is what separates a DIYer from a master mechanic. You have to account for the "drag" of the real world.

Practical Steps for Using Simple Machines

If you're looking to apply these concepts to a project—maybe you're building a deck or trying to move a heavy safe—keep these tactical insights in mind:

- Check your pivot point first. If a lever feels too hard to move, move your fulcrum closer to the load. Even an inch makes a massive difference in the math.

- Inspect the "threads" on your ramps. If you're using a ramp to move a motorcycle into a truck, ensure the surface has high friction (traction) even though the machine itself is designed to reduce the "lifting" work.

- Compensate for rope stretch. When using pulleys for heavy lifting, remember that nylon and poly ropes stretch. This absorbs your effort. Use low-stretch static ropes for maximum mechanical advantage.

- Lubricate every moving contact point. A dry screw or a rusty pulley can lose up to 30% of its effectiveness to friction. A little bit of lithium grease or even WD-40 (though that's a solvent, not a true long-term lubricant) changes the game.

The world is just a collection of these six shapes. Once you start seeing the wedges in your kitchen and the levers in your toolbox, you stop fighting against heavy objects and start letting geometry do the heavy lifting for you. It's not about working harder; it's about using a longer lever.