Drawing a lighthouse seems like it should be the easiest thing in the world. It’s just a cylinder, right? A tall tube with a little hat on top sitting on a rock. But honestly, most people who sit down to try a simple lighthouse line drawing end up with something that looks more like a cartoon salt shaker than a majestic maritime beacon. There is a specific kind of magic in a minimalist line—a way to capture the salt spray and the looming height of a structure without over-complicating the ink.

I’ve spent years looking at architectural sketches and nautical charts. The best ones aren't the most detailed. They’re the ones where the artist knew exactly which lines to leave out. When you’re staring at a blank piece of paper, the goal isn't to draw every single brick. The goal is to suggest the soul of the building.

The Geometry Most People Get Wrong

The biggest mistake? Treating the lighthouse like a 2D rectangle. Even in a very basic sketch, you have to account for the "taper." Real lighthouses, like the famous Cape Hatteras in North Carolina or the iconic Portland Head Light, aren't perfectly straight up and down. They have a subtle flare at the base. This is structural; they need to withstand massive wind loads.

If you draw two parallel vertical lines, your lighthouse will look like a pipe. It feels dead. To give it life, you need a slight inward tilt as you move toward the lantern room. We’re talking maybe a three to five-degree angle. It’s barely there, but your brain picks up on it instantly.

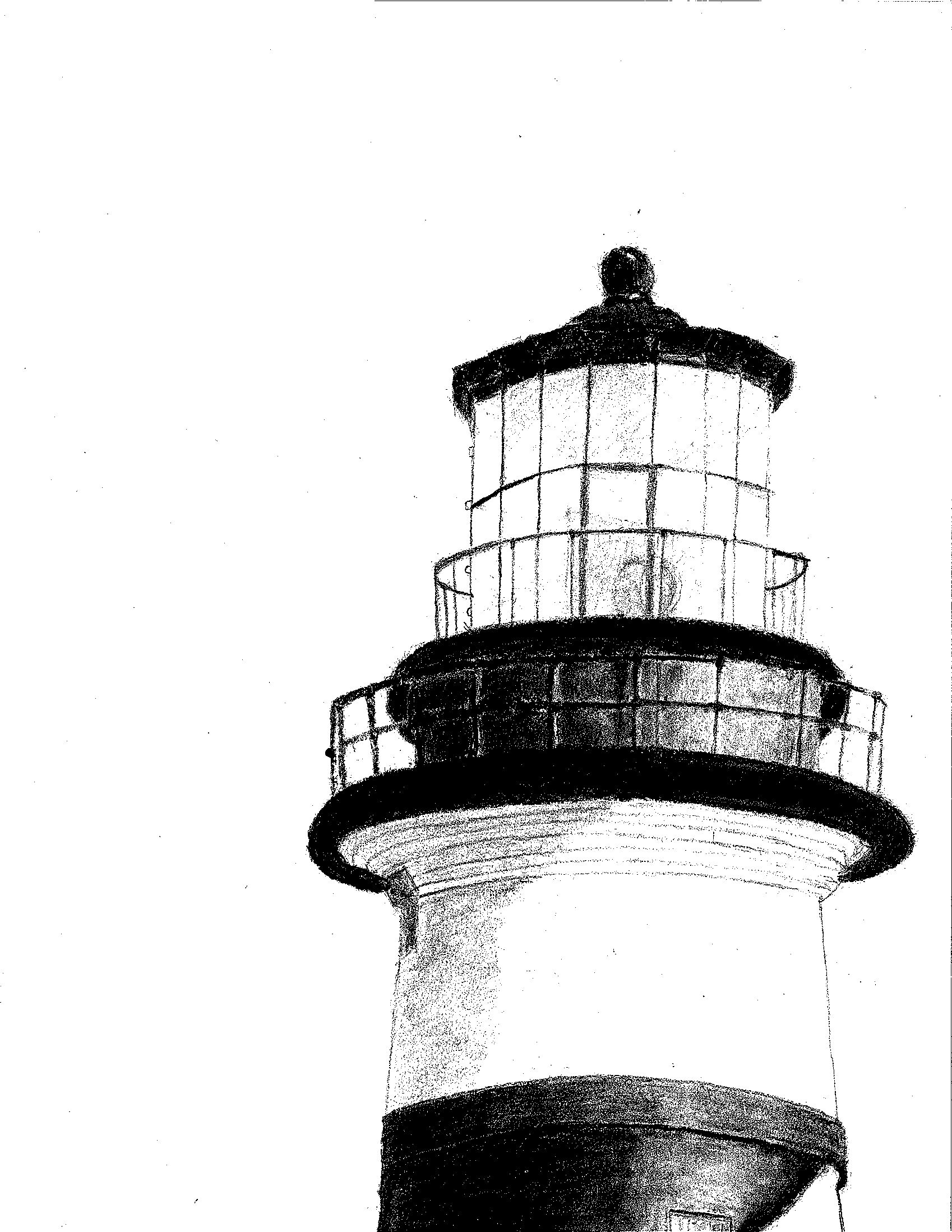

Another thing is the "horizon line" perspective. If you are looking up at a lighthouse, the horizontal lines of the railings and the gallery deck should curve slightly upward. If you're looking down from a cliff, they curve downward. Most beginners draw these lines perfectly flat. That’s why the drawing feels like a sticker stuck onto a page rather than an object in 3D space.

Master the Lantern Room Without Losing Your Mind

The top of the lighthouse—the lantern room—is where everyone panics. There are glass panes, railings, ventilators, and the dome. It's a lot. In a simple lighthouse line drawing, you have to simplify these into basic shapes.

Think of the lantern room as a small glass cylinder sitting on a wider platform. Don't draw every single pane of glass. Instead, draw the vertical supports (the mullions) and maybe a single diagonal "glint" line to suggest the reflection of light on glass.

- The Gallery: This is the walkway around the light. Draw this as a thin ellipse that wraps around the tower.

- The Dome: It’s a half-circle, but it usually has a little "finial" or weather vane on top. This tiny detail adds a huge amount of professional polish.

- The Light: Don't draw a literal lightbulb. Use a series of radiating lines or just leave the space white to suggest the brilliance of the Fresnel lens.

Rock, Water, and Weight

A lighthouse doesn't float in a vacuum. It’s anchored. Usually to something jagged and unforgiving.

When you’re doing line art, the temptation is to draw every single wave and every single crack in the rock. Don’t do that. It creates visual noise that distracts from your main subject. Instead, use "weighted lines." Use a thicker pen or press harder on the side of the rocks where the shadows would fall. This gives the drawing a sense of gravity.

For the water, three or four horizontal, slightly broken lines are usually enough to tell the viewer, "Hey, this is the ocean." If you add too much detail to the water, you lose the "simple" part of your simple lighthouse line drawing. It’s about restraint.

The Secret of the Fresnel Lens

If you want to sound like an expert—or at least draw like one—you have to understand the Fresnel lens. Invented by Augustin-Jean Fresnel in the early 1800s, these lenses use a series of prisms to take a small light source and throw it for miles.

In a line drawing, you can represent this with a series of concentric circles or a "honeycomb" pattern inside the lantern room. You don't need to be precise. Just a few curved lines suggest that complex glasswork. It’s a "shorthand" that seasoned artists use to convey complexity without actually doing the work of drawing a thousand prisms. It works every time.

Why Minimalism Wins in Maritime Art

There’s a reason why line art is so popular for coastal decor. It’s clean. It feels like a sea breeze. When you start adding heavy shading or complex cross-hatching, the drawing starts to feel heavy.

Think about the work of minimalist illustrators. They use "suggestive lines." A line that starts, breaks for a few millimeters, and then continues. This mimics how light actually hits a surface. Our eyes fill in the gaps. If you draw a solid, heavy black line around the entire lighthouse, you've essentially created a coloring book page. If you break that line where the sun would be hitting the tower, you’ve created a piece of art.

Tools of the Trade

You don't need a $50 set of pens. Honestly, a simple Micron 05 or even a decent gel pen will do the trick. The key is the paper. If you use paper that is too toothy (like cold-press watercolor paper), your lines will look shaky. For a simple lighthouse line drawing, you want a smooth Bristol board or a high-quality sketchbook. You want that pen to glide.

- Start with a 2H pencil. It’s light and won't smudge.

- Define the central axis. Make sure your lighthouse isn't leaning (unless it's the one in Skagen, Denmark, which has its own issues).

- Ink the "structural" lines first. The main tower and the base.

- Add the "character" lines last. The windows, the door, and the tiny seagull in the distance.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

I see people trying to draw the beam of light using yellow markers or heavy shading. It almost never looks good in a line drawing. If you want to show the light beam, use "negative space." Draw the clouds or the night sky around where the beam would be, leaving the beam itself as the white of the paper. It’s a much more sophisticated way to handle light.

Another thing: the windows. Lighthouse windows are tiny. They have to be, otherwise the wind would blow them in. Don't draw big house windows. Draw small, dark squares. And remember, they follow the curve of the tower. They shouldn't be perfectly centered if the tower is viewed from an angle.

Putting It Into Practice

Now that you've got the theory, it's about the execution. A simple lighthouse line drawing is a fantastic way to practice your hand-eye coordination because it combines rigid architecture with organic elements like rocks and waves. It’s the perfect "warm-up" sketch.

Start by choosing a real-world reference. The Split Rock Lighthouse in Minnesota is great for beginners because it sits on a very distinct cliff. The Eddystone Lighthouse is more of a challenge because of its base.

💡 You might also like: Why Neck Length Braided Bob Hairstyles Are Taking Over Your Feed

Once you’ve finished the drawing, take a step back. If it looks too busy, grab an eraser (if you still have pencil marks) and see if you can "open up" the drawing. Sometimes, removing three or four lines makes the whole thing feel twice as professional.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Practice the Taper: Spend five minutes just drawing "tapered cylinders." Focus on making the two sides symmetrical without using a ruler.

- Study the Fresnel: Look up a close-up photo of a Fresnel lens. Try to simplify that complex shape into just four or five lines.

- The One-Pen Challenge: Try to complete an entire sketch using only a single thickness of pen. This forces you to use "line breaks" and spacing to create depth rather than relying on different pen tips.

- Go Vertical: Most people draw on landscape paper. Turn your sketchbook vertically (portrait mode). It forces you to emphasize the height and grandeur of the tower, which is the whole point of a lighthouse anyway.

The beauty of a lighthouse is its isolation. It stands alone against the elements. Your drawing should reflect that. Give it space on the page. Let it breathe. A few well-placed lines are always better than a hundred messy ones.