It starts with a hiss. That low-fidelity hum on a 1964 monaural recording that shouldn't have worked. Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel were, by all accounts, a failed folk duo when their first album flopped. They’d already split up. Paul was in London, playing damp clubs. Art was back at school. Then, a producer named Tom Wilson—the same guy who helped Bob Dylan go electric—decided to overdub electric guitars and drums onto a quiet, acoustic track called "The Sound of Silence." He didn't even tell them he was doing it. That single moment changed Simon and Garfunkel music forever, turning a funeral-paced folk song into a folk-rock juggernaut that defined a generation’s anxiety.

People forget how weird they actually were.

They weren't the Stones. They weren't even the Beatles. They were two Jewish kids from Queens who grew up obsessing over the Everly Brothers and ended up writing some of the most complex, harmonically dense music ever to hit the Billboard charts. If you listen closely to those early records, you aren't just hearing catchy melodies. You're hearing a weird tension. It’s the sound of two people who, quite frankly, often couldn't stand each other, but whose voices locked together with a mathematical precision that felt almost supernatural.

The sonic architecture of a fractured friendship

When we talk about the technical side of their discography, we have to talk about Roy Halee. He was their engineer and basically the "third member" of the group. Halee didn't like standard studio setups. For "The Boxer," he recorded the drums in a hallway next to an elevator shaft to get that massive, crashing reverb on the snare. That wasn't a digital plug-in. That was a guy dragging a drum kit into a corridor because it sounded "right."

The vocal blend is where the real magic (and the real work) happened. Art Garfunkel had this ethereal, angelic tenor that could hover over a track like a ghost. Paul Simon wrote the lyrics, played the intricate fingerstyle guitar, and sang the grounded, earthy lower harmony. But they didn't just sing together; they phrasing-matched. Every "s" sound, every breath, every consonant was synchronized.

It’s exhausting to listen to if you’re a singer because you realize how much rehearsal it took.

🔗 Read more: Donnalou Stevens Older Ladies: Why This Viral Anthem Still Hits Different

Then there’s the songwriting. Paul Simon wasn't just writing "protest songs." He was writing about urban isolation. Look at "I Am a Rock." It’s a song about a guy so terrified of being hurt that he builds a literal wall around his life. It’s dark. It’s cynical. But because the melody is so bright and the harmonies are so lush, people hum it at grocery stores without realizing they’re singing about a nervous breakdown.

Why the big hits feel different 50 years later

Most people know the "Greatest Hits" version of the story. You’ve got "Mrs. Robinson," "Cecilia," and "Bridge Over Troubled Water." But the real depth of Simon and Garfunkel music lies in the deep cuts and the sheer sonic experimentation of their final album.

Take "The Only Living Boy in New York." Paul wrote it as a message to Art, who was away in Mexico filming Catch-22. Paul felt abandoned. To capture that feeling of vast, empty space, they recorded the backing vocals in a massive echo chamber, layering their voices over and over—some accounts say up to 50 times—to create a "choir" that sounds like it's coming from another dimension.

It’s haunting. Honestly.

- Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. (1964): The debut. Pure folk. It didn't sell, but it has "Benedictus," which shows off their classical training.

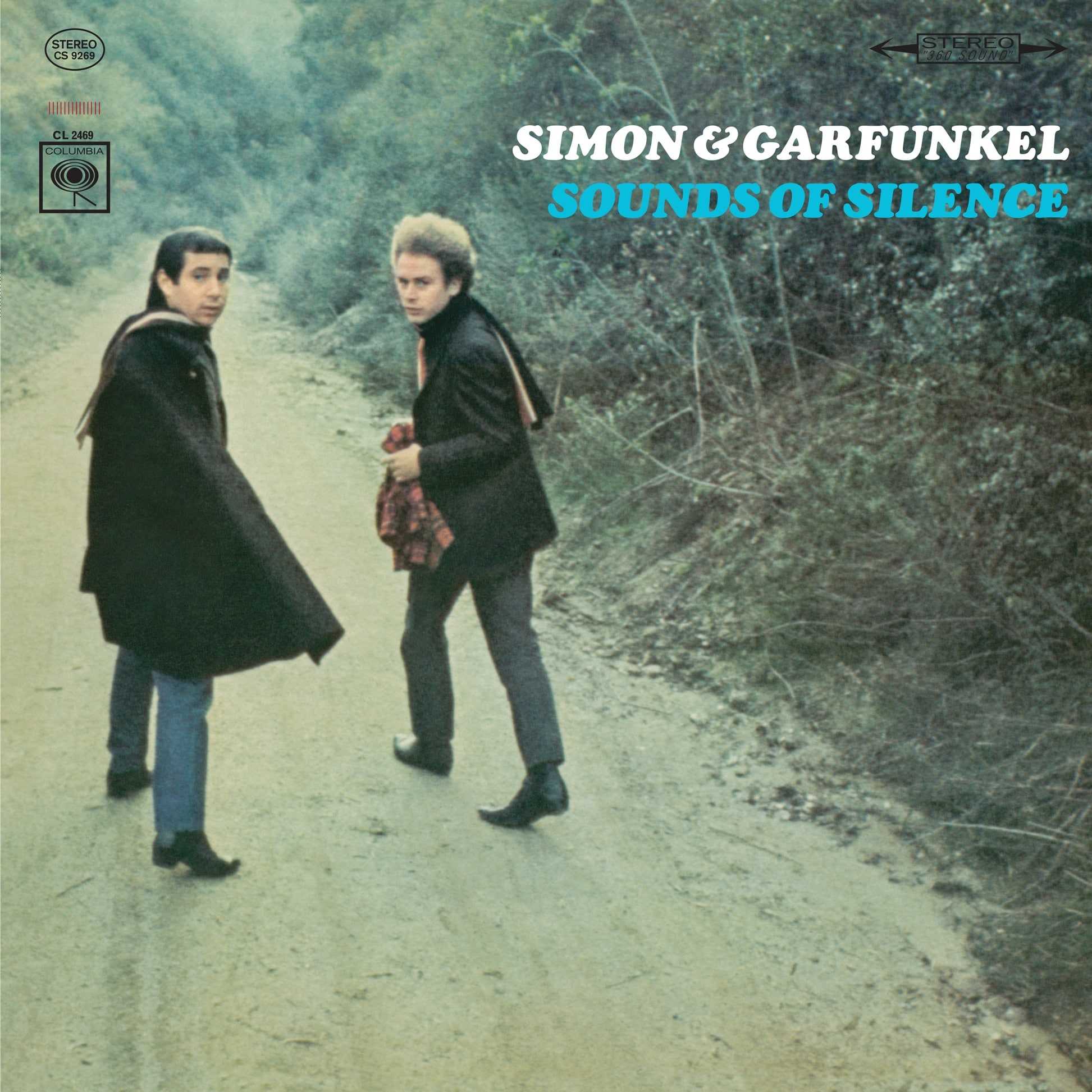

- Sounds of Silence (1966): The pivot to folk-rock. This is where they found their "voice."

- Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966): Pure sophistication. Songs like "For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her" show Art’s vocal peak.

- Bookends (1968): A concept album about the cycle of life. It’s short, sharp, and incredibly avant-garde for its time.

- Bridge Over Troubled Water (1970): The swan song. It’s huge, gospel-influenced, and world-weary.

The tension between them fueled the creativity. By the time they were recording Bridge Over Troubled Water, they were barely speaking. Paul wanted to explore world music (you can hear the beginnings of this in "El Condor Pasa"), while Art was leaning into big, cinematic ballads. That friction created a record that feels like it's bursting at the seams. It’s arguably one of the greatest albums ever made, yet it’s the sound of a partnership disintegrating in real-time.

💡 You might also like: Donna Summer Endless Summer Greatest Hits: What Most People Get Wrong

The myth of the "gentle" folk duo

There is a misconception that their music is just "mellow" or "coffee shop" music. That’s a total misunderstanding of the lyrics.

Paul Simon was a "mean" writer in the best sense of the word. He was sharp, observant, and occasionally cruel. In "A Hazy Shade of Winter," he isn't singing about flowers; he's singing about the terrifying speed of time and the failure of dreams. "America" isn't a patriotic anthem; it’s a road trip song about two people looking for a country they can’t find and realizing they’re lost even though they're sitting right next to each other.

"Kathy’s Song" is perhaps the most honest love song ever written because it admits to doubt. It’s not "I will love you forever." It’s "I’m standing here in the rain, and I’m worried that I’m losing my mind and my connection to you."

That honesty is why teenagers in 2026 still listen to this stuff. The technology changes. The clothes change. But that feeling of being 22, sitting on a bus, and feeling like you have no idea who you are? That’s universal. Simon and Garfunkel captured that specific flavor of loneliness better than almost anyone in the history of recorded sound.

The technical legacy: How to listen today

If you want to actually hear what made them special, don't just stream the hits on your phone speakers. You’ll miss the "air."

📖 Related: Do You Believe in Love: The Song That Almost Ended Huey Lewis and the News

The way Halee recorded these sessions was designed for stereo depth. In "The Boxer," the way the fingerpicked guitar panned from left to right was revolutionary. You need a decent pair of headphones to hear the subtle hiss of the tape and the way the voices slightly bleed into each other’s microphones. It makes it feel human. It makes it feel like they’re in the room.

How to dive deeper into their catalog:

- Listen to the "Old Friends" live versions: Their 1981 Central Park concert is legendary, but the 1960s live recordings show how much power they had with just two voices and one guitar. No backing band. Just raw harmony.

- Track the transition to solo careers: You can hear the "Simon" in "Cecilia" (the rhythmic experimentation that led to Graceland) and the "Garfunkel" in "Bridge Over Troubled Water" (the soaring, melodic purity).

- Analyze the lyrics of "The Dangling Conversation": It’s a song about a couple who has run out of things to say, using Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost as metaphors. It’s incredibly "academic," but it hits like a ton of bricks.

Actionable ways to experience the music now

If you’re new to the discography or a long-time fan looking for a fresh perspective, stop shuffle-playing. Simon and Garfunkel music was designed for the album format.

Start with Bookends. It’s only 29 minutes long. Listen to it from start to finish. It moves from the heavy, synth-distorted "Save the Life of My Child" into the quiet, observational "Old Friends." Notice how they use found sound—real recordings of elderly people talking in a park—to bridge the tracks. This wasn't just pop music; it was audio documentary.

Next, look for the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival footage. They were one of the only acts there without a massive psychedelic light show or a wall of Marshall stacks. They just stood there and sang. The audience, which had just seen Janis Joplin and would soon see Jimi Hendrix set a guitar on fire, was dead silent. That’s the power of the blend.

Finally, pay attention to the percussion. From the heavy stomp of "Cecilia" to the delicate "Bookends Theme," Paul Simon was obsessed with rhythm long before he ever went to South Africa. He used his guitar as a drum, hitting the wood and muting the strings. It’s a masterclass in how to make a small sound feel massive.

The partnership ended in 1970, and despite a few reunions, the bridge remained burnt. But the records remain. They are frozen moments of two voices trying to find a way to sound like one, even when the people behind them were moving in opposite directions. That’s the real story. It’s messy, it’s beautiful, and it’s still remarkably loud.

Practical Steps for Collectors:

- Seek out the 1970 UK pressings of Bridge Over Troubled Water if you’re into vinyl; the mastering is famously "warm."

- Use "The Sound of Silence" (Acoustic Version) as a benchmark for testing new speakers. If you can hear the faint click of the guitar pick, the clarity is right.

- Read "Lyrics 1964-2016" by Paul Simon to see how he stripped away the folk clichés of the era to find a more prose-like, modern voice.