If you’ve ever looked at a medical diagram of the human torso, you probably noticed a small, fist-sized organ tucked away on the left side, just under the ribcage. That’s the spleen. Most people go their entire lives without giving it a single thought. It’s the "quiet" organ. But for anyone living with sickle cell disease, the spleen isn't just a quiet neighbor—it becomes a central character in a very complex biological drama.

Honestly, the relationship between sickle cell disease and the spleen is one of the most critical aspects of hematology. It’s also one of the most misunderstood.

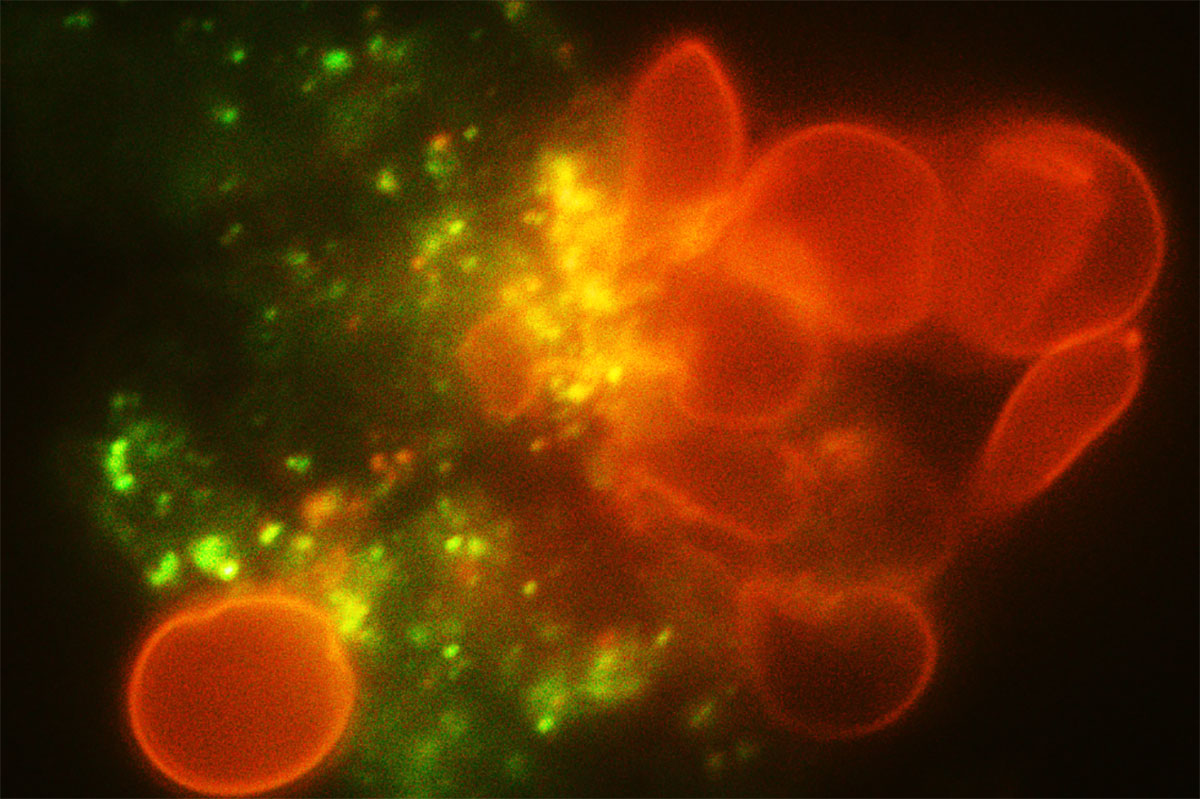

The spleen is basically your body’s quality control center for blood. It filters out old or damaged red blood cells and keeps a reserve of white blood cells ready to fight off infections. It’s a literal sieve. But when red blood cells are shaped like crescents or sickles instead of flexible discs, they don't slide through that sieve. They get stuck. They clog the pipes. And that’s where the trouble starts.

Why the Spleen Struggles with Sickle Cell

Red blood cells in a healthy body are like soft, squishy doughnuts. They can deform and squeeze through tiny capillaries without a problem. In sickle cell disease, the hemoglobin—the protein that carries oxygen—clumps together. This turns the cell into a rigid, sticky "C" shape.

When these rigid cells hit the narrow corridors of the spleen, they don't bend. They jam.

This creates a traffic backup. It's called vaso-occlusion. Because the spleen is so packed with tiny vessels, it is often the first organ to suffer permanent damage. In many children with sickle cell, the spleen actually stops working before they even reach middle school. Doctors call this "functional asplenia." The organ is still there physically, but it’s essentially gone "dark." It can't filter blood, and more importantly, it can't help the immune system fight off specific types of bacteria.

The Silent Danger of Splenic Sequestration

We need to talk about one of the most frightening complications: splenic sequestration. This is a medical emergency that parents of kids with sickle cell are taught to watch for from day one.

Basically, a massive amount of blood gets trapped—or "sequestered"—inside the spleen. Think of it like a sponge that suddenly soaks up half the body's blood supply. The spleen gets huge and hard. You can actually feel it poking out from under the ribs. Because so much blood is stuck in the spleen, there isn’t enough circulating in the rest of the body. Blood pressure drops. The heart races. It’s life-threatening.

Researchers like those at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) have spent decades tracking these crises. They've found that it most commonly happens in infants and toddlers. Why? Because as patients get older, the repeated clogging of the spleen causes it to scar and shrink. By adulthood, many sickle cell patients have a "fibrotic" spleen—it's shriveled up to the size of a prune. You can't have a sequestration crisis if the organ is already scarred over, but you lose all the protective benefits of having a spleen in the first place.

The Infection Connection

If the spleen isn't working, you’re at a massive disadvantage against germs. The spleen is specifically designed to catch "encapsulated" bacteria—think Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. These are the bugs that cause pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis.

For a long time, this was the leading cause of death for children with sickle cell disease.

Everything changed when the PROPS study (Prophylactic Penicillin Study) was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in the 1980s. Dr. Gaston and her team proved that giving young kids daily penicillin could slash the risk of deadly infections by over 80%. It was a total game-changer. It’s why today, if you have a baby diagnosed with sickle cell through newborn screening, they start twice-daily penicillin almost immediately. It’s not because they’re sick now; it’s because their spleen isn't there to protect them later.

Life Without a Spleen

Living with functional asplenia isn't a death sentence, but it requires a different rulebook. You have to be aggressive about vaccines. We aren't just talking about the standard childhood shots. People with sickle cell disease need extra doses of the pneumococcal vaccine and the meningococcal vaccine.

Also, a fever is never "just a fever."

In a person with a healthy spleen, a 101°F fever might mean a day on the couch with some soup. For someone with sickle cell, it’s an automatic trip to the emergency room for IV antibiotics. Because without that splenic filter, a minor infection can turn into full-blown sepsis in just a few hours. It’s a high-stakes way to live, but with the right protocols, it’s manageable.

Misconceptions About Spleen Removal

Sometimes, doctors recommend a splenectomy—the surgical removal of the spleen. This usually happens if a child has had multiple sequestration crises or if the spleen has become so large it’s causing pain or interfering with eating.

A common myth is that removing the spleen "cures" the blood issues. It doesn't.

The sickling still happens in the rest of the body. You’re just removing the site of a specific, dangerous complication. In fact, some studies suggest that after a splenectomy, patients might actually be at a slightly higher risk for certain types of blood clots or pulmonary hypertension. It’s always a trade-off. It’s about choosing the lesser of two evils: the risk of a life-threatening sequestration event versus the long-term management of being "asplenic."

Nuance in Different Genotypes

It’s worth noting that not all sickle cell is the same. People with HbSS (the most common form) usually lose splenic function very early. However, those with HbSC or Sickle Beta-Plus Thalassemia might keep their spleen working much longer—sometimes well into adulthood.

Ironically, this can be a double-edged sword.

Because their spleens remain "active," they remain at risk for sequestration crises much later in life than someone with HbSS. An adult with SC disease might suddenly have a spleen crisis at age 30, which is almost unheard of in SS patients. This is why personalized hematology is so vital. You can't just apply the "standard" sickle cell timeline to everyone.

What You Can Actually Do

If you or a loved one are navigating sickle cell disease and the spleen, there are concrete steps that make a massive difference in outcomes.

Palpate the Spleen Regularly

Parents of young children should ask their hematologist to teach them how to feel for the spleen. Knowing what "normal" feels like for your child allows you to spot an emergency before it becomes catastrophic. If the spleen feels harder or larger than usual, it’s an immediate ER visit.Hydration is Non-Negotiable

When you’re dehydrated, your blood gets thicker. Thicker blood is more likely to "sludge" in the spleen. Drinking water isn't just about thirst; it's about keeping the blood fluid enough to navigate the splenic filters.Stay Current on "Extra" Vaccines

Don't just rely on the basic school requirements. Ensure the Prevnar 13 and Pneumovax 23 schedules are followed strictly, as these specifically target the gaps left by a non-functioning spleen.Fever Protocols Save Lives

Have a thermometer that works. If the temperature hits 101.3°F (38.5°C), go to the hospital. Do not wait for the morning. Do not wait for the clinic to open.Hydroxyurea and New Therapies

Talk to your specialist about disease-modifying therapies. Hydroxyurea has been shown to reduce the frequency of sickling, which in turn can sometimes preserve splenic function for a longer period. Newer drugs like Voxelotor (Oxbryta) work by helping hemoglobin hold onto oxygen better, potentially preventing the initial sickling that clogs the spleen.

The spleen might be a small organ, but its role in sickle cell is massive. Understanding that it’s essentially a "clogged filter" helps make sense of why certain treatments—like daily penicillin or emergency transfusions—are so necessary. It’s about outsmarting the biology of the disease to keep the rest of the body running smoothly.

Actionable Insight: If you haven't had an ultrasound of the upper left quadrant in several years, ask your hematologist if a "baseline" image of your spleen is warranted. Knowing the current size and degree of scarring can help your medical team better predict your risk for sequestration or infection. Always keep a medical alert card or bracelet that specifies "Functional Asplenia" to ensure ER doctors prioritize your care during a fever.