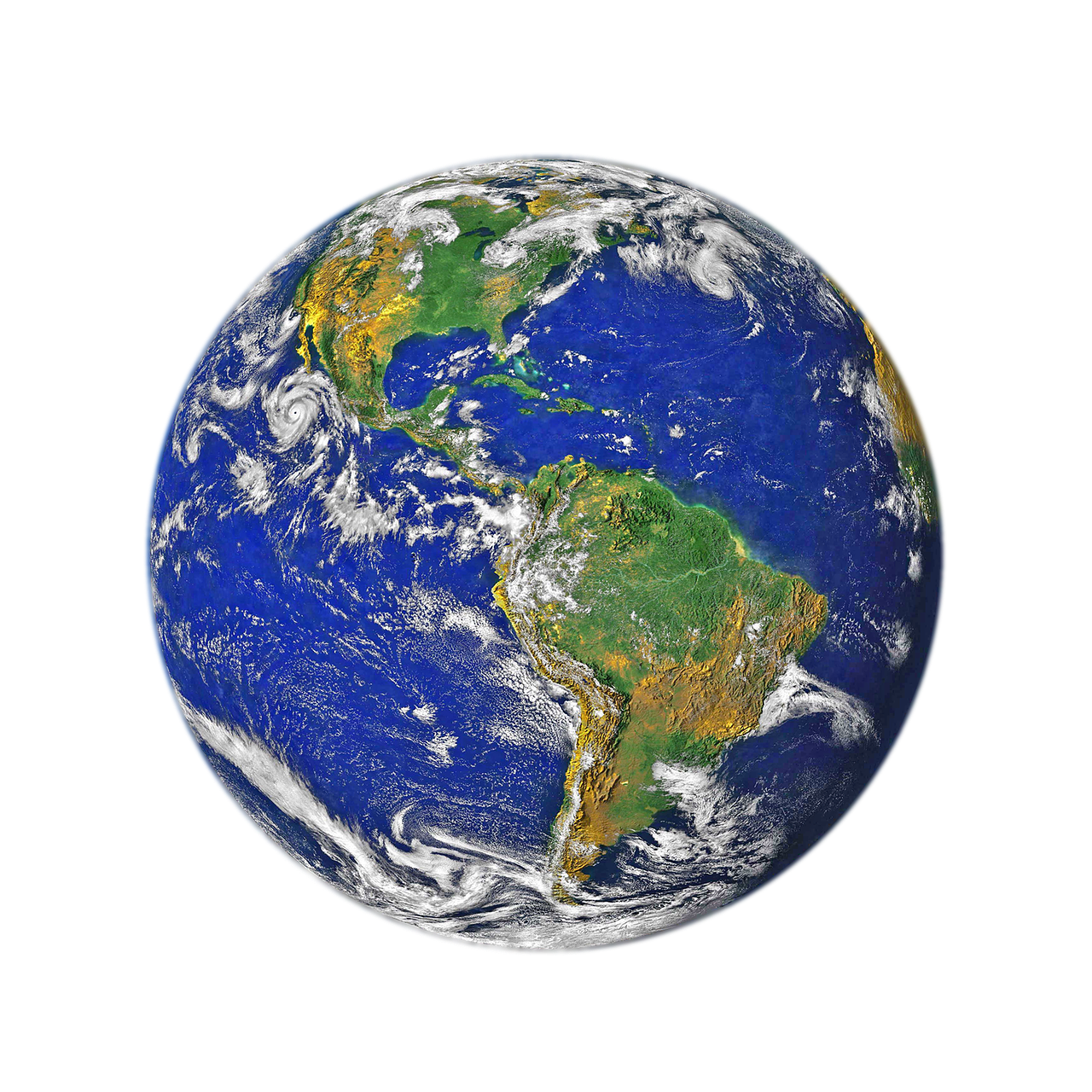

You’ve seen the marbles. Most people, when they ask a search engine to show me pictures of planet earth, expect that perfect, vibrant blue sphere hanging in a void of pitch black. It’s iconic. It’s also, quite often, a composite. Looking at Earth from space isn't just about clicking a shutter button; it’s a massive technological feat that involves stitching together thousands of data points, managing extreme light exposure, and occasionally dealing with the fact that our atmosphere is actually kind of a blurry mess.

NASA’s "Blue Marble" from 1972 is perhaps the most famous photo in human history. Taken by the Apollo 17 crew, it was a single shot with the sun directly behind the spacecraft. That’s rare. Most modern "photos" you see are actually data visualizations. When we look at the Earth today through the lens of a satellite like the DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory), we are seeing something much more complex than a simple Polaroid from the heavens.

The Reality Behind the Most Famous Earth Photos

There is a huge difference between a photograph and an image. If you want to see the real Earth, you have to understand how we actually get these shots. Take the 2012 "Blue Marble" version. It’s stunning. High resolution. Vivid greens in the Amazon. But it wasn't taken in one go. Because the Suomi NPP satellite orbits so close to the Earth, it can’t see the whole thing at once. It’s like trying to take a photo of a basketball while your camera is an inch away from the surface. You get a patch of texture, not the ball.

Scientists have to take "swaths" of data as the satellite zips around the poles. They then wrap those strips around a digital sphere. If they didn’t do this, the edges would look distorted, sort of like a map of the world where Greenland looks the size of Africa. When you ask to show me pictures of planet earth, you’re often looking at a masterpiece of data science rather than a single "click" of a camera.

The Pale Blue Dot: A Perspective Shift

Carl Sagan famously requested that Voyager 1 turn its camera around one last time in 1990. The result was a grainy, noisy image where Earth is less than a single pixel. It’s not "pretty" in the traditional sense. There are no swirling white clouds or deep blue oceans visible. It's just a speck. This photo matters because it’s one of the few that hasn't been color-corrected to look "natural." It shows the sheer scale of the void.

📖 Related: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

Looking at that speck, you realize how much work goes into making the Earth look like the Earth in our textbooks. Space is bright. The sun is an unfiltered nuclear furnace. To get a clear image, satellites have to use filters—usually Red, Green, and Blue—and then stack them. If the timing is off by even a fraction of a second, the clouds move, and you get a weird "ghosting" effect where the colors don't line up.

Where to Find the Raw, Unedited Earth

If you're tired of the polished, Photoshopped versions, you should check out the Himawari-8 or Himawari-9 feeds. This is a Japanese geostationary satellite. It sits over the same spot on Earth all the time. It uploads a "True Color" image every ten minutes.

It’s honestly breathtaking because it’s not perfect. You can see the haze of wildfires in Australia or the yellow dust blowing off the Gobi Desert. You see the planet as a living, breathing, slightly dusty organism. It’s not the bright, saturated blue of a screensaver. It’s deeper. More navy. More real.

Another great source is the ISS High Definition Earth Viewing (HDEV) experiment. These are cameras mounted on the International Space Station. Because the ISS is only about 250 miles up, you don't see the whole circle. You see the curve. You see the "limb" of the atmosphere—that thin, glowing blue line that separates us from certain death. It’s terrifyingly thin. It looks like a layer of onion skin.

👉 See also: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

Why the Colors Keep Changing

You might notice that in some pictures of Earth, the oceans are turquoise, and in others, they are almost black. This isn't just because of different cameras. It’s physics.

- Rayleigh Scattering: This is why the sky is blue. When sunlight hits the atmosphere, the shorter blue wavelengths scatter more. From space, this can make the Earth look like it has a blue glow or "haze."

- Phytoplankton: In some parts of the ocean, massive blooms of microscopic plants turn the water bright green. Satellites like Aqua and Terra are specifically designed to look for these color shifts to track ocean health.

- The Angle of the Sun: Just like "golden hour" on Earth makes your selfies look better, the angle of the sun in space changes everything. Glint—the reflection of the sun off the ocean—can turn the water into a blinding silver mirror.

NASA's Earth Observatory is probably the best place for the "weird" stuff. They don't just show me pictures of planet earth as we see it; they show it in infrared. This lets us see heat. We can see the "urban heat island" effect where cities like New York or Tokyo are glowing hot compared to the surrounding countryside. It’s a different kind of beauty, one that reveals the impact we have on the crust of the world.

The Problem With "Night Lights" Imagery

We’ve all seen the beautiful images of Earth at night with the cities glowing like spiderwebs of gold. These are some of the most popular requests when people want to see the planet. But here’s the thing: those images are almost always "Black Marble" composites.

The satellites have to wait for cloud-free nights over every single square inch of the globe. This takes months. Then, they have to filter out the light from the moon, which is surprisingly bright. They also have to account for "airglow," which is a faint light emitted by the atmosphere itself. What you end up with is a map of human civilization, but it’s a time-lapse, not a snapshot. If you were actually standing on the moon looking at the dark side of the Earth, you wouldn't see the cities that clearly. The clouds would block most of them.

✨ Don't miss: The iPhone 5c Release Date: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Ways to Explore Earth Imagery

If you really want to dive into this, don't just look at Google Images. The quality there is hit-or-miss, and you often get AI-generated fakes or old, low-res renders.

- Visit NASA’s EPIC (Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera) Gallery. This camera is on the DSCOVR satellite, located at the Lagrange point 1, about a million miles away. It takes a full-disk image of the Earth every hour. You can watch the planet rotate in near real-time. This is as close to a "live webcam" of the whole Earth as we have.

- Use Google Earth Engine. This isn't just the map you use for directions. The Engine allows you to look at time-lapses of specific spots on Earth over the last 40 years. You can see glaciers retreating in Alaska or the expansion of Las Vegas. It’s the best way to see how the "pictures" change over time.

- Check out the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. This is a database maintained by Johnson Space Center. It contains over 1.5 million photos taken by actual humans on the ISS. These are "handheld" shots. They have a grit and a perspective that robotic satellites just can’t replicate. You’ll see the grain of the film (in older shots) or the slight blur of a fast-moving station.

Looking at the Earth shouldn't just be a passive thing. Every time you see a new image, look for the "limb"—the edge of the atmosphere. Notice how thin it is. Look at the patterns of the clouds; they follow the same fluid dynamics as cream stirred into coffee. When you ask to show me pictures of planet earth, you aren't just looking at a rock in space. You're looking at a closed system, a tiny oasis that is much more fragile than the bright, bold "Blue Marble" posters make it out to be.

Start with the EPIC gallery today. See what the weather looks like over the Atlantic right now. It’s much more grounding than looking at a static image from 1972. You’ll see the shadows of the clouds, the reflection of the sun, and the actual, shifting face of the only home we've ever known.