"How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?"

It’s the most famous line in detective fiction. Sherlock Holmes, the human calculator in a deerstalker, lived by it. He was the ultimate champion of logic, a man who saw a tobacco ash and reconstructed a life. So, it’s kinda weird that his creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, spent the latter half of his life talking to dead people and chasing fairies. But even within the original stories, the tension between Sherlock Holmes and the devil—or at least the idea of the supernatural—is everywhere.

The Victorian era was obsessed with the séance room. While the Industrial Revolution was building steam engines, the spiritualist movement was trying to build bridges to the "Other Side." Holmes was the antidote to that. He was the cold, hard light of reason. Yet, time and again, Doyle pitted his detective against crimes that looked, smelled, and felt like the work of the devil himself.

People often forget that the most famous Holmes story, The Hound of the Baskervilles, is basically a horror movie. You have an ancient family curse, a hellish hound with flaming eyes, and a desolate moor that feels like the edge of the world. It’s the perfect playground for the demonic.

The Diabolical Nature of the Baskerville Curse

Let’s talk about that dog. When Dr. Mortimer comes to 221B Baker Street, he doesn't just bring a case; he brings a legend. He reads a manuscript from 1742 about Hugo Baskerville, a man so "wild, profane, and godless" that he literally triggered a localized apocalypse. Hugo’s deal with the darkness resulted in a "foul thing, a great, black beast, shaped like a hound, yet larger than any hound that ever mortal eye has rested upon."

Mortimer, a man of science, is terrified. He tells Holmes, "There is a realm in which the most acute and most experienced of detectives is helpless."

He’s basically saying the devil is outside Sherlock’s jurisdiction.

Holmes’s reaction? He yawns. He calls it a "fairy tale." To Holmes, the "devil’s agents" are always made of flesh and blood. They use phosphorus to make dogs glow. They use stilts or trickery or hidden passages. But the brilliance of the story is how much Doyle leans into the atmosphere of the infernal. The Grimpen Mire is a literal deathtrap, swallowing ponies whole. It’s a landscape that feels cursed.

Is there a devil in Dartmoor? No. But the fear of the devil is the real weapon. Stapleton, the villain, understands that a rational man can be paralyzed by an irrational fear. He uses the myth of the demonic to mask a very terrestrial motive: greed.

👉 See also: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

Why We Want Holmes to Fight the Supernatural

There is a specific itch that Sherlock Holmes and the devil narratives scratch. We live in a world that feels chaotic. Sometimes, evil feels so profound that "he had a bad childhood" or "he wanted the inheritance" doesn't feel like enough of an explanation. We want a monster.

But then we want Holmes to come in and prove the monster isn't real.

It’s a cycle of catharsis. We get the thrill of the ghost story with the safety of the scientific resolution. In The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire, Holmes is even more blunt. He receives a letter about a woman sucking her baby’s blood and snaps. "Anything card-indexed?" he asks. "Sailing pillars? Flying dogs? This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply."

He’s a gatekeeper. He protects the reader from the encroaching darkness of the Victorian "occult revival."

Interestingly, Doyle himself was failing at this in real life. By the 1920s, Doyle was arguably the most famous Spiritualist in the world. He believed in the Cottingley Fairies. He believed he could communicate with his son who died in the Great War. It’s one of the great ironies of literature: the man who created the most rational character in history ended up believing in things that would have made Sherlock Holmes laugh in his face.

The Devil in the Details: Professor Moriarty

If Holmes has a "Satan," it’s Moriarty. Holmes doesn't describe him as a mere criminal. He calls him "the Napoleon of Crime." But look at the language in The Final Problem.

Holmes describes Moriarty as a "force" rather than a man. He sits at the center of a web, motionless, but radiating evil across London. When they finally meet at the Reichenbach Falls, it isn't just a fight between a detective and a math professor. It’s framed as a cosmic struggle. It’s Michael casting out Lucifer.

Moriarty represents the "intellectual devil." He is what happens when logic is stripped of morality. If Holmes is pure reason used for good, Moriarty is pure reason used for chaos. In that sense, the Sherlock Holmes and the devil connection isn't about pitchforks. It’s about the terrifying potential of the human mind to go dark.

✨ Don't miss: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Other "Demonic" Encounters in the Canon

- The Devil’s Foot: In this story, people are literally driven insane by a hallucinogenic powder. They see things so horrifying they die of pure terror. The physical symptoms—distorted faces, frozen screams—look like demonic possession. Holmes, of course, almost kills himself trying to prove it's just a chemical reaction.

- The Creeping Man: A professor starts acting like a literal beast, climbing walls and howling. It feels like a werewolf story. It turns out to be "serum of langur." It’s science gone wrong, but the imagery is straight out of a grimoire.

- The Speckled Band: A "snake from hell" kills a girl in a locked room. The atmosphere of the crumbling ancestral home and the "gypsies" on the lawn creates a sense of ancient, lurking evil.

The Modern Obsession: Crossover Fiction

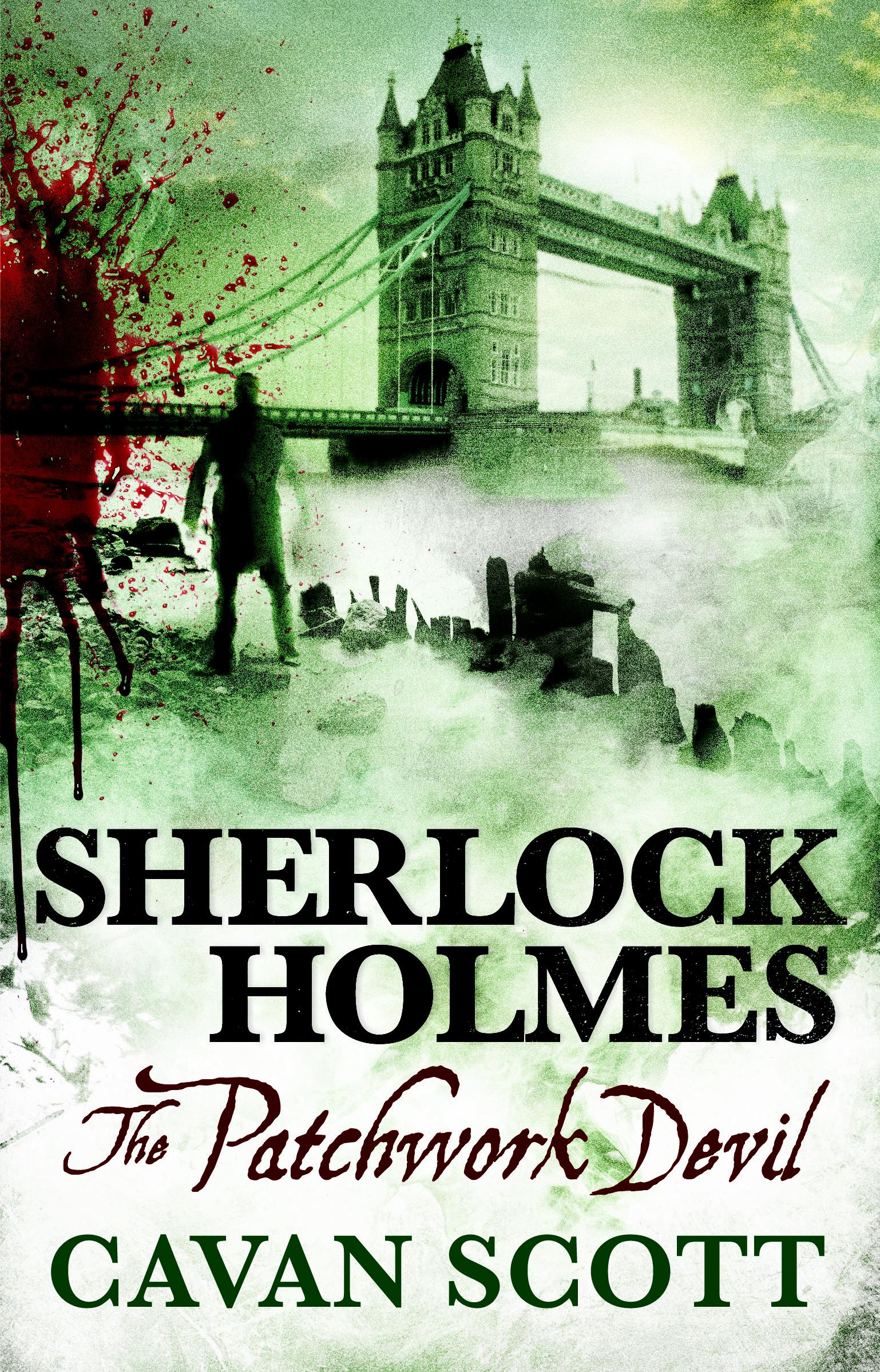

Because Doyle’s estate eventually entered the public domain, other writers couldn't resist actually putting Sherlock Holmes and the devil in the same room. You have books like The Canary Trainer or the various "Sherlock Holmes vs. Cthulhu" pastiches.

These stories work because they challenge Holmes's fundamental axiom. What happens to the "eliminating the impossible" rule when the impossible is standing right in front of you?

In many of these non-canonical stories, Holmes has to adapt. He doesn't stop being a scientist; he just expands his science to include the laws of magic or the divine. It’s a fascinating evolution of the character. It suggests that even if the devil were real, Holmes would just try to find out what kind of mud was on his hooves.

Fact-Checking the "Occult" Holmes

A lot of people think Doyle wrote Holmes because he loved science. Actually, he grew to hate Holmes. He thought the detective was a "distraction" from his "serious" work, which included his massive volumes on the history of Spiritualism.

Doyle once told a friend that he felt he was being used by "higher forces" to bring the message of the afterlife to the masses, and Holmes was just the bait.

But the fans didn't care about the ghosts. They wanted the tobacco ash. They wanted the footprints.

There is a real-world parallel here. Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle were actually friends. Houdini, the master of illusion, spent his time debunking mediums and "demonic" psychics. Doyle, the creator of the world's greatest skeptic, was the one getting fooled. Houdini once showed Doyle a trick—a simple sleight of hand—and Doyle was so convinced it was "real magic" that he refused to believe Houdini’s explanation of how it was done.

It’s wild. The guy who wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles couldn't see the phosphorus on the dog when it was right in front of him.

🔗 Read more: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

How to Read Holmes with a "Dark" Lens

If you want to dive deeper into the darker side of Baker Street, don't just look for the word "devil." Look for the gothic elements.

The Victorian era was terrified of "degeneration." They feared that humans were sliding backward into animality. This is why so many Holmes villains are described as having "ape-like" features or "reptilian" eyes. To the Victorians, this was the modern equivalent of the demonic. Evil wasn't a fallen angel; it was a biological failure.

Holmes is the "New Man." He is the evolution. He is the one who keeps the shadows at bay.

When you read The Sign of Four, notice how the "Small" and his "island companion" are treated like demonic intruders in the heart of London. The city itself becomes a character—a foggy, labyrinthine hellscape where anything can happen.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Mystery Fan

If you're fascinated by the intersection of the rational and the macabre in the Holmes universe, here is how you can explore it further:

- Read "The Devil's Foot" first. It is the closest Doyle ever got to a true "horror" vibe within the short stories. Pay attention to the descriptions of the physical horror.

- Visit the Dartmoor National Park. If you’re ever in the UK, go to the setting of The Hound of the Baskervilles. When the mist rolls in, you'll understand why people believed in hell-hounds. It’s eerie.

- Compare Doyle to Poe. Edgar Allan Poe created the detective genre with C. Auguste Dupin, but Poe leaned much harder into the macabre. Seeing how Holmes "cleaned up" the genre is a great way to understand the transition from Gothic horror to modern mystery.

- Watch the 1984 Jeremy Brett series. Specifically, look for the "Hound" episode. It captures the atmosphere of the "supernatural vs. rational" better than any high-budget movie.

- Study the Cottingley Fairies case. If you want to see the "Sherlock Holmes" creator lose his mind to the supernatural, this is the definitive historical event. It involves two girls, some paper cutouts, and a very gullible Sir Arthur.

The relationship between Sherlock Holmes and the devil isn't about whether demons exist. It's about the human need for an answer. Whether the "monster" is a fallen angel or a man with a bottle of luminous paint, we just want someone to shine a lantern on it and tell us we don't need to be afraid of the dark anymore.

Holmes does that. He takes the devil and turns him into a data point. And in a world that often feels like it's losing its mind, that’s a pretty comforting thought.

Check the original texts. You'll find that for every mention of a "curse," there is a corresponding mention of a "test tube." That was Doyle's genius, even if he didn't always follow his own advice. He gave us a hero who could look the devil in the eye and ask for his permit.