Shellac is weird. It’s basically refined bug poop—specifically the resinous secretions of the Kerria lacca female scale insect. While most people today associate the word with a shiny manicure or perhaps a vintage dresser, there’s a much stranger, more industrial side to this story. You've probably seen the phrase shellac to all trains floating around in historical archives or logistical footnotes, and if you haven’t, you're about to see why it was once the most important shipping directive in the world.

Think about the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The world was moving fast. Electricity was the new god, and everyone was trying to figure out how to insulate wires without the whole thing catching fire. They needed something that could resist moisture, stay hard at high temperatures, and—this is the big one—act as a perfect dielectric.

Enter the lac bug.

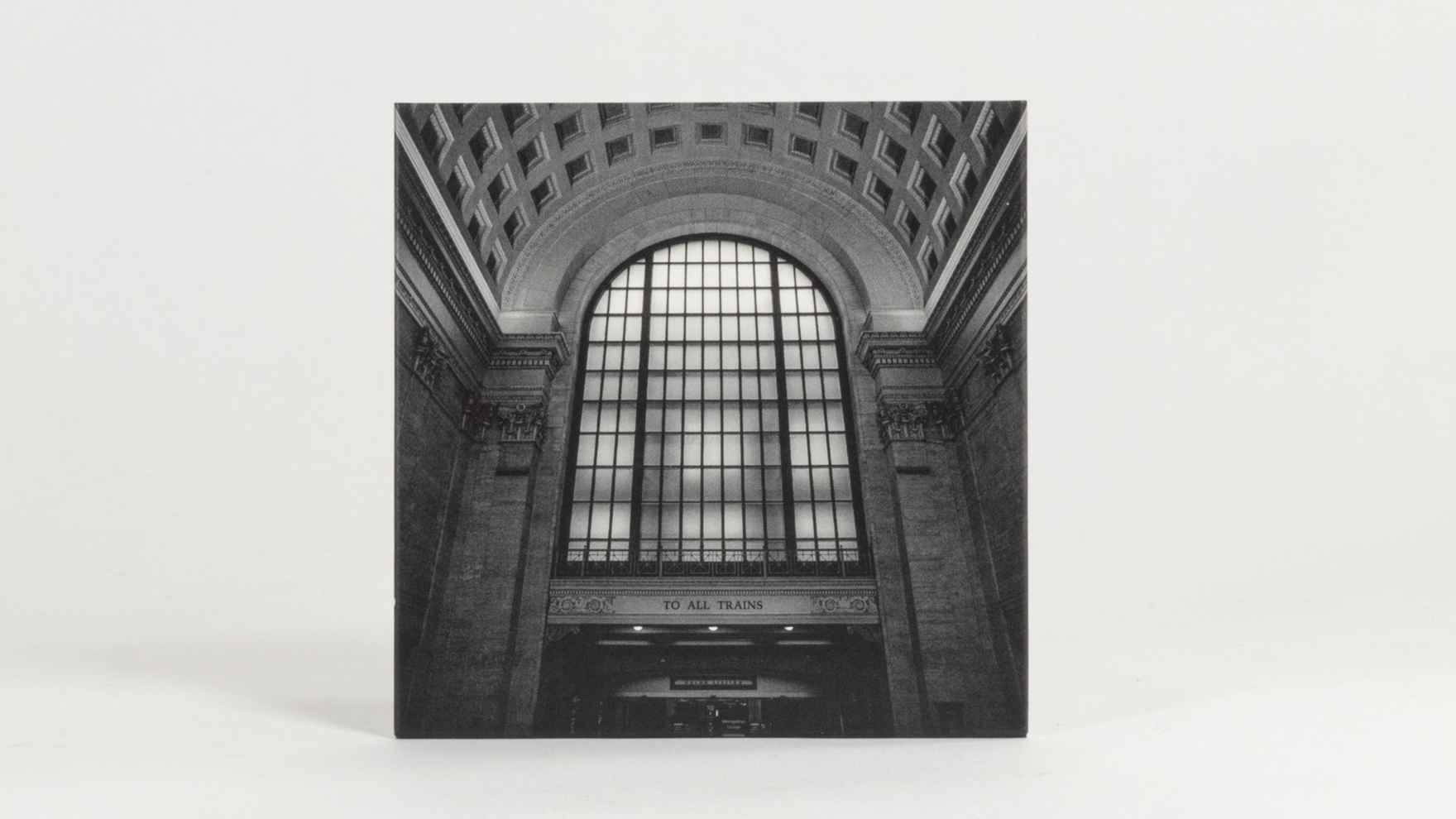

It sounds crazy. We built the modern world on the back of a tiny red insect found in India and Thailand. When the demand for shellac spiked, it didn't just affect furniture makers. It affected every single logistical artery in the developed world. Shipping "shellac to all trains" became a literal necessity to keep the gears of the Second Industrial Revolution turning. If the shellac didn't arrive, the gramophone records didn't get pressed, the munitions didn't get coated, and the electrical grids didn't expand.

Why the Railroads Cared About Bug Resin

Railroads weren't just moving passengers. They were the internet of their day, the high-speed data transfer of physical goods.

If you were a station master in 1910, a shipment of shellac was treated with the kind of reverence we might give to a crate of lithium-ion batteries today. It was volatile in its own way—not because it would explode, but because it was temperature-sensitive and prone to "blocking" or sticking together in high heat.

The directive to get shellac to all trains wasn't some poetic phrase. It was a logistical priority. If a shipment of seedlac or button lac was sitting on a hot dock in Calcutta or a humid warehouse in New York, the product was ruined. It would melt into a solid, useless brick.

Actually, the scale of this trade is hard to wrap your head around. By the 1920s, the United States was importing millions of pounds of the stuff every year. Why? Because before Bakelite and other modern plastics, shellac was the only game in town for molding complex shapes. You had to get it from the forest to the factory as fast as humanly possible.

📖 Related: New Update for iPhone Emojis Explained: Why the Pickle and Meteor are Just the Start

The Gramophone Crisis and the War Effort

Let’s talk about records. Before vinyl, there was shellac.

Every single 78 RPM record produced before the late 1940s was made of a shellac compound. If you’ve ever dropped an old record and watched it shatter into a million jagged pieces, that’s the shellac. It’s brittle. It’s hard. And for about fifty years, it was the only way humanity could store sound.

This created a massive bottleneck.

During World War II, the "shellac to all trains" mentality shifted from commercial greed to national security. The government actually started rationing shellac. They needed it for more than just music; they needed it for "low-tech" high-tech solutions. It was used as a coating for artillery shells to prevent corrosion. It was used in the primer of explosives. It was used to insulate the instruments in the cockpits of fighter planes.

In 1942, the War Production Board in the U.S. essentially took over the shellac trade. They told the public to turn in their old 78s so they could be melted down and recycled for the war effort. It’s honestly kind of wild to think that a Louis Armstrong record might have been melted down to help coat a shell destined for a battlefield in Europe.

The Science: Why Synthetic Alternatives Almost Failed

Chemists hated shellac. Not because it was bad, but because it was inconsistent.

Since it’s a natural product, the quality depends on what the trees were doing that year, how much rain fell in India, and how well the insects were feeding. It's a complex polymer of hydroxy fatty acids. Most synthetic resins created in the early 1900s couldn't match its unique properties:

👉 See also: New DeWalt 20V Tools: What Most People Get Wrong

- It’s non-toxic (you literally eat it today on shiny apples and jelly beans).

- It’s UV resistant.

- It has a low melting point but is incredibly durable once set.

- It's a "natural" plastic that's biodegradable.

When the chemical industry tried to replace it, they ran into a wall. Bakelite was great, but it was heavy and couldn't be dissolved into a simple spirit varnish the way shellac could. For decades, the phrase shellac to all trains remained a reality because the labs simply couldn't beat the bugs.

Misconceptions About the "Shellac To All Trains" Phrase

You’ll sometimes hear people say this was a specific telegraph code or a secret society password. It wasn't. It’s more of a cultural relic of a time when logistics were manual.

It basically meant "Priority One."

In the shipping manifests of the era, certain commodities were flagged for immediate transfer to any departing locomotive. Perishables like meat and milk usually got this treatment. But shellac was the only non-food item that regularly received this level of urgency. If a train was leaving, and there was a crate of shellac on the platform, you put it on that train. No excuses.

There's a famous story—likely slightly exaggerated but based in truth—of a New Jersey record pressing plant that nearly went under during a heatwave because their shipment was delayed. They ended up hiring local kids with blocks of ice to sit in the boxcars just to keep the resin from melting before the train could pull out.

The Modern Reality: Is It Still Relevant?

You’d think we’d be done with it. We have high-density polyethylene, epoxy, and every flavor of acrylic imaginable.

But shellac never went away.

✨ Don't miss: Memphis Doppler Weather Radar: Why Your App is Lying to You During Severe Storms

If you take a time-release vitamin or a coated aspirin today, you are likely consuming "Pharmaceutical Glaze." That's just a fancy name for shellac. If you buy a high-end acoustic guitar, like a Martin or a Gibson, the "French Polish" finish that makes it resonate so beautifully? That’s shellac, hand-rubbed over weeks.

The logistics have changed, sure. We don’t have steam locomotives frantically hauling bug resin across the Midwest anymore. But the supply chain is just as fragile. Most of the world’s supply still comes from the same regions in India and Thailand. When there’s a crop failure or a political upheaval in those areas, the price of everything from wood finish to Skittles spikes.

How to Work With Shellac (The Expert Way)

If you're looking to actually use this stuff—maybe for a DIY project or because you're a purist—don't buy the pre-mixed cans from the big box stores. They have a shelf life. After a year or two, the shellac won't dry properly. It stays tacky forever.

Instead, do what the old-timers did. Buy the flakes.

You mix the flakes with denatured alcohol yourself. It’s a bit of a pain, but the results are incomparable. You can control the "cut"—which is just a fancy way of saying the ratio of flakes to alcohol. A "two-pound cut" means two pounds of flakes in a gallon of alcohol.

Honestly, it’s the most forgiving finish in the world. If you mess it up, you just add more alcohol and wipe it away. You can’t do that with polyurethane. You can’t do that with lacquer.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you’re fascinated by this weird intersection of entomology and industrial history, here’s how to dive deeper:

- Check your labels. Look for "Confectioner’s Glaze" or "E904" on food packaging. You’ll be surprised how often you’re eating the same stuff that used to be shipped "to all trains."

- Visit a luthier. If you know someone who builds or repairs violins or high-end guitars, ask them about French Polishing. It’s a dying art that relies entirely on shellac.

- Experiment with flakes. If you’re into woodworking, order a small bag of "Dewaxed Blonde" flakes. Mix a small batch and try it on a scrap of walnut. The depth of color is something no modern synthetic can replicate.

- Research the Lac Marketing Board. Look into the historical exports of Bihar and West Bengal. The economic history of these regions is inextricably linked to the global demand for this specific resin.

Shellac isn't just a relic of the past. It’s a reminder that even in an age of synthetic everything, sometimes the best solution is a natural one that's been around for millions of years. Whether it’s on a train in 1905 or in a laboratory in 2026, the humble lac bug still holds a grip on our industrial world.