It happened in a lab in Scotland.

Most people think science moves in these grand, cinematic sweeps, but the cloning of sheep Dolly was actually a mess of failed attempts and late nights at the Roslin Institute. Before Dolly, the scientific consensus was pretty much set in stone: once a cell decides what it’s going to be—like a skin cell or a liver cell—it can’t go back. It’s a one-way street. Then, in 1996, Ian Wilmut, Keith Campbell, and their team basically proved the entire world wrong by turning back the clock on a single cell taken from a mammary gland.

Honestly, it’s kind of wild that it worked at all. They didn't just "make" a sheep. They managed to trick a specialized adult cell into thinking it was a brand-new embryo.

The messy reality behind the cloning of sheep Dolly

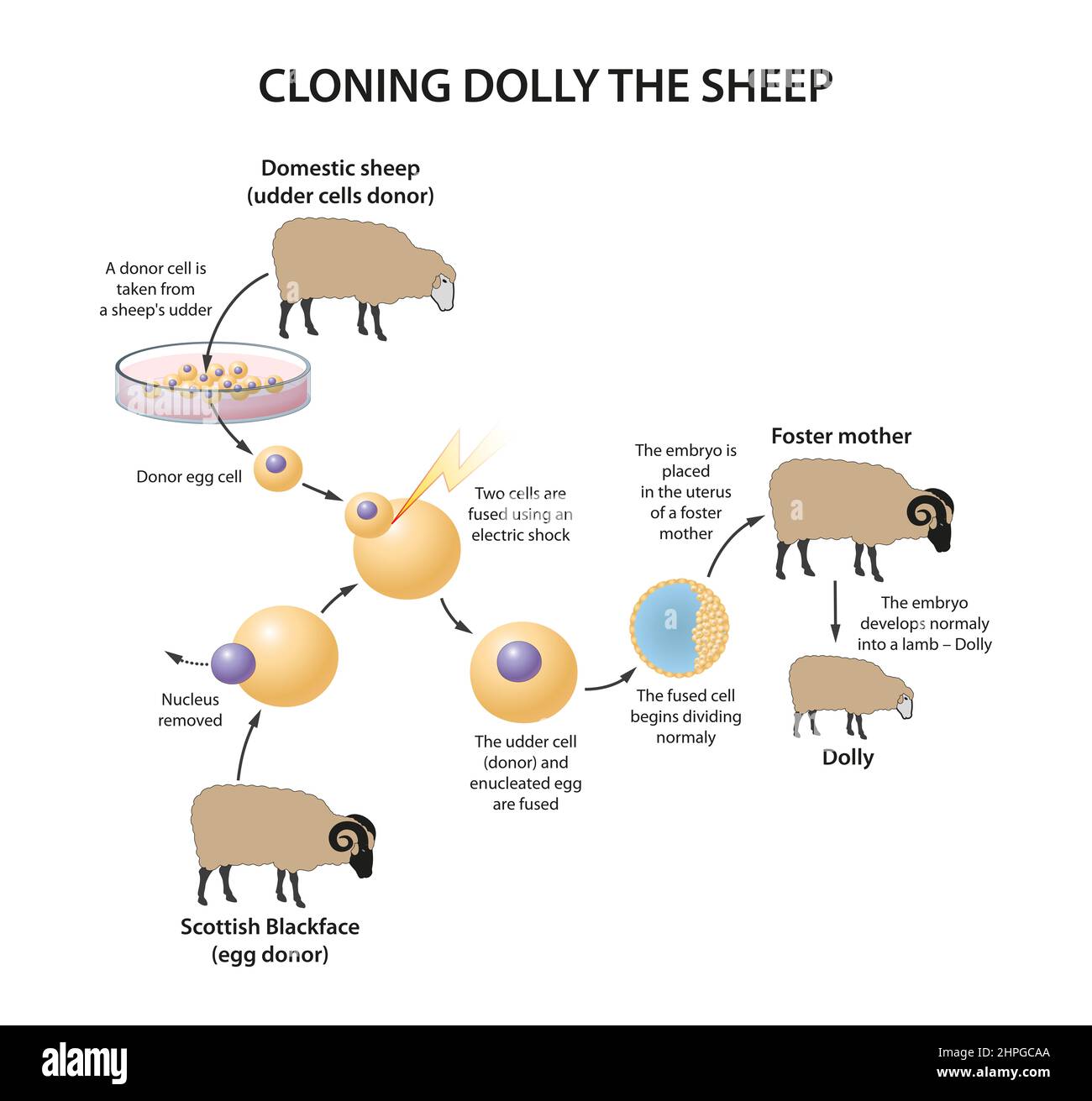

We usually hear the highlight reel. The real story is that Dolly was the only success out of 277 attempts. Imagine that for a second. Two hundred and seventy-seven tries. The researchers were using a technique called Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT). Basically, they took an unfertilized egg from a Scottish Blackface ewe and sucked out its nucleus—the part containing the DNA. Then, they took a cell from a Finn Dorset sheep’s udder and fused it with that empty egg using pulses of electricity.

It wasn't a "copy-paste" job like you do on a laptop. It was delicate, frustrating work that failed over and over until cell number 6LL3 finally started dividing.

Why does the "udder" part matter? Well, that’s actually how she got her name. Because the cell came from a mammary gland, the lab techs—with a bit of 90s humor that might not fly as well today—named her after Dolly Parton.

✨ Don't miss: Apple AirPods Pro 2 Hearing Aid: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the world absolutely freaked out

When the news broke in early 1997, the public reaction was somewhere between fascination and pure horror. It wasn’t just about a sheep. People immediately jumped to the "Boys from Brazil" scenario. If you can clone a sheep, you can clone a person, right?

The media went into a frenzy. Time Magazine and Newsweek had covers that looked like sci-fi movie posters. President Bill Clinton even stepped in, calling for a ban on federal funding for human cloning research almost immediately. There was this profound sense that we had opened a door we weren't supposed to touch.

But for scientists, the breakthrough wasn't about making carbon copies of people. It was about reprogrammability. It proved that DNA isn't a permanent script. It’s more like a piece of software that can be rebooted if you know which buttons to press. This paved the way for stem cell research, specifically induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which don't require embryos at all. Without Dolly, we might not be looking at modern regenerative medicine the same way.

Was Dolly "old" from the start?

Here is where things get a bit sad and a lot more complicated. Dolly lived for six and a half years. For a sheep, that’s a bit short—they usually go for 10 or 12.

She started developing arthritis when she was only four. People started whispering. Was she "born old"? Since she was cloned from a six-year-old sheep, did her cells think they were already middle-aged? Scientists looked at her telomeres—the little caps at the end of DNA strands that shorten as we age. Dolly’s telomeres were indeed shorter than a normal sheep her age.

However, the "premature aging" narrative is still debated. She eventually had to be euthanized in 2003 because of a progressive lung disease called sheep pulmonary adenomatosis. The thing is, this disease is caused by a virus (JSRV) that was floating around the flock anyway. It wasn't necessarily a "cloning glitch."

🔗 Read more: TI-84 Plus CE Cost: Why It’s Still $100+ and How to Pay Less

The legacy of the Roslin Institute team

Ian Wilmut and Keith Campbell became household names, but their partnership eventually soured over who deserved the lion's share of the credit. It’s a classic science drama. While Wilmut was the face of the project, he later acknowledged that Campbell deserved about 66% of the credit for the technical breakthrough regarding the cell cycle.

What most people get wrong about cloning today

You might think that after the cloning of sheep Dolly, we’d have armies of cloned livestock by now.

We don't.

Cloning is still incredibly inefficient. It’s expensive, it’s prone to errors, and many cloned animals suffer from "Large Offspring Syndrome," where they grow too big for the womb. It’s not a viable way to feed the world. Instead, the technology has branched off into very specific niches:

- Elite Livestock: Some ranchers clone prize-winning bulls for breeding purposes, using the clone as a "genetic placeholder."

- Pet Cloning: Companies like ViaGen will clone your dog for about $50,000. It won't have the same soul or personality, but it'll look just like your old friend.

- Endangered Species: Scientists are trying to use SCNT to bring back the Black-footed ferret and even the Woolly Mammoth (though that’s a whole different ballgame involving CRISPR).

The real value of Dolly wasn't the sheep herself—it was the proof of concept. She showed us that biology is much more plastic than we ever imagined.

How to track the future of this tech

If you're interested in where the spirit of the Dolly experiment is going next, don't look at sheep. Look at the "Gene Editing" space.

- Research Epigenetics: This is the study of how cells "remember" their identity. Dolly was the ultimate test of epigenetics.

- Follow the Woolly Mammoth project: Colossal Biosciences is effectively the modern spiritual successor to the Roslin Institute’s ambition, though they use different methods.

- Check out iPSC developments: Look up Shinya Yamanaka. He won a Nobel Prize for something that Dolly made possible: turning adult skin cells back into stem cells without needing any eggs or embryos.

Dolly is currently stuffed and standing on a rotating plinth in the Royal Museum of Scotland. She looks like any other sheep. But that one animal changed the trajectory of biological science forever, proving that "impossible" is usually just a temporary status.

👉 See also: PNC App Not Working: Why You Can’t Log In and How to Fix It Right Now

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

If you want to see the actual science in action, visit the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh to see Dolly in person. To dive deeper into the ethical side, read the original 1997 Nature paper titled "Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells"—it's surprisingly readable for a landmark paper. Alternatively, monitor the FDA's ongoing rulings on cloned food products to see how this 90s tech is finally hitting your dinner plate in 2026.