Color is weird. Seriously. You might look at a specific ocean wave and see a vibrant, punchy green, while the person standing right next to you insists it's definitely blue. This isn't just about being stubborn or having a "different opinion." It's actually rooted in how our brains process the electromagnetic spectrum. When we talk about shades of blue and green, we are wading into the "cyan" gap—the most contested territory in human vision.

Most people assume color is an objective fact. It isn't. It’s a physiological hallucination.

The light hits your retina, specifically the cone cells, and your brain does a massive amount of post-processing to decide what name to give that data. Because the wavelengths for blue and green sit right next to each other—roughly 450 to 495 nanometers for blue and 495 to 570 for green—the border is incredibly fuzzy. Honestly, it's a miracle we agree on the color of the sky at all.

The Teal Trap: Where Blue and Green Collide

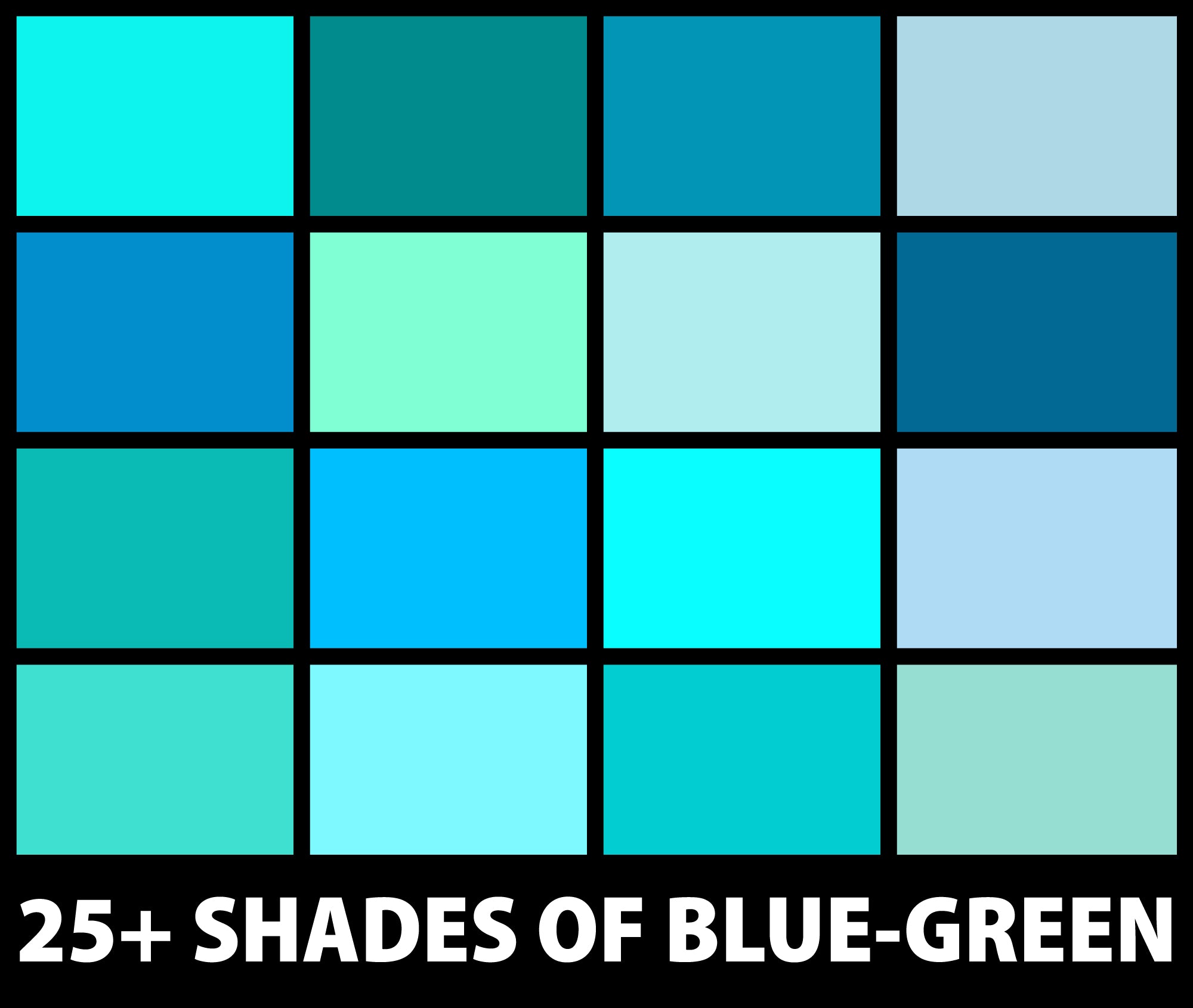

What do you call that color between a clear summer sky and a shallow tropical lagoon? Some say turquoise. Others say cyan. If you're a designer, maybe you’re thinking about "Tiffany Blue," which, despite the name, is technically a robin's egg blue that leans heavily into the green side of the wheel.

This overlap is where the drama happens. In 2017, a survey conducted by Optical Express went viral because it showed a specific shade of blue-green that 64% of people called green, but after seeing it next to two distinctly blue objects, many changed their minds to blue. It’s all about context. Our eyes don’t see colors in isolation; they see them in relation to what’s nearby.

Take "Cyan" for example. In the CMYK printing world, it’s a primary color. In the RGB digital world, it’s a secondary color made by mixing equal parts green and blue light. But ask a random person on the street to point at cyan, and they’ll likely hesitate. Is it a "light blue" or a "bluish green"? The answer depends entirely on your culture, your vocabulary, and even the literal physical structure of your eyes.

Why Your Brain Struggles with the Blue-Green Border

There is a fascinating concept in linguistics called "Grue." No, not the monster from the old Zork games.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Historically, many languages didn't have separate words for blue and green. They used one term to cover the entire cool-toned spectrum. In Japanese, the word ao can refer to both a blue sky and a green "go" light on a traffic signal. In Old Welsh, the word glas could mean blue, green, or even gray.

When you don't have a specific word for a color, your brain actually becomes less efficient at distinguishing between those shades. This is known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Research by Jules Davidoff on the Himba tribe in Namibia showed that because their language has many words for types of green but no distinct word for blue, they could spot a "different" shade of green that looked identical to Westerners, yet they struggled to pick a blue square out of a circle of green ones.

It’s wild. Your vocabulary is basically a filter for your reality.

The Physics of the Spectrum

Light isn't colored. It’s just energy moving at different frequencies.

- Blue light has shorter wavelengths and higher energy. It scatters more easily, which is why the sky looks blue.

- Green light sits in the middle. Our eyes are actually most sensitive to green because it’s where the sun’s output is strongest.

Because we are so sensitive to green, we can distinguish between thousands of forest tones—moss, lime, emerald, hunter, chartreuse—much better than we can distinguish between various shades of deep blue. We evolved in the trees, after all. We needed to know if a leaf was "new growth green" or "rotten green."

Iconic Shades of Blue and Green You See Every Day

Let’s get specific. If you're looking to paint a room or design a brand, you aren't just looking for "blue-green." You're looking for a mood.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Viridian is a deep, cool green that feels expensive. It’s got a heavy dose of blue, making it feel stable and sophisticated. It was a favorite of 19th-century painters because it didn't fade like earlier green pigments made from toxic arsenic. Yes, people used to literally die for the perfect shade of green wallpaper.

Cerulean is the color of a "perfect" sky. It gained massive pop-culture fame thanks to Meryl Streep’s monologue in The Devil Wears Prada, where she explains how a single color choice by high-end designers eventually trickles down to a bargain bin sweater. It’s a blue that feels expansive. It doesn't have the yellow undertones that make something look "teal."

Mints and Pistachios are the lightweights. These are green-heavy but washed out with white. They feel "clean." This is why hospitals and vintage kitchens used them so much. They suggest a sterile, fresh environment without being as jarring as a pure white.

The Biology of "Blue" Eyes and "Green" Eyes

Here is a fact that usually breaks people's brains: there is no blue or green pigment in human eyes.

If you have blue eyes, the iris is actually translucent or brown-ish. The color you see is the result of Tyndall scattering—the same reason the sky looks blue. Light hits the stroma in the iris and scatters, reflecting back the shorter blue wavelengths.

Green eyes are even rarer and more complex. They occur when there’s a tiny bit of melanin (brown pigment) mixed with that blue-scattering effect. It’s a literal optical illusion happening in your face. This is why people with "hazel" or "sea-green" eyes often find that their eye color "changes" depending on what shirt they are wearing. They aren't changing color; they’re just reflecting different parts of the shades of blue and green in their environment.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

How to Use These Colors Without Messing Up

If you are trying to use these colors in your life, you have to account for the "temperature."

- Check the Undertone: A "warm" blue has a hint of red or yellow in it (like a periwinkle or a greenish-teal). A "cool" blue is pure or leans toward violet.

- The 60-30-10 Rule: If you’re decorating, don't use equal amounts of blue and green. It creates visual "vibration" that makes people feel uneasy. Use 60% of one, 30% of a secondary, and 10% for an accent.

- Lighting is Everything: A shade of "Seafoam" that looks amazing in a sunny showroom will look like a depressing "Hospital Gray" in a basement with cool LED bulbs. Always test a swatch in the actual room.

Most people get color wrong because they think it's static. It’s not. It’s a conversation between light, surface, and your weird, wonderful brain.

Actionable Steps for Choosing the Right Shade

Don't just pick a color off a tiny 1-inch square at the hardware store. That is a recipe for regret.

- Buy a Sample Can: Paint a 2x2 foot square on at least two different walls. Look at it at 10:00 AM, 4:00 PM, and 8:00 PM under artificial light.

- Use the "Squint Test": If you’re trying to see if a blue and green go together, squint your eyes until the details blur. If the two colors turn into a muddy brown mess, they lack enough contrast. If they stay distinct but harmonious, you’ve got a winner.

- Digital Translation: If you're a creator, remember that "True Green" (Hex #00FF00) looks terrible on screens. It's too bright. Always pull your greens slightly toward the blue or yellow side to make them feel "organic" and readable.

Whether you're looking at a shades of blue and green palette for a new website or just trying to win an argument about whether your partner's shirt is navy or forest, remember that vision is subjective. Your "teal" is someone else’s "azure." And honestly? That’s okay. The complexity of the cool-color spectrum is what makes the world look deep instead of flat.

Stop worrying about the "correct" name and start paying attention to how the light actually hits the surface. You'll start seeing colors you never noticed before.