Walk into a room where the carpet is a shade of green so specific it feels like a memory you aren't supposed to have. That is the immediate, visceral punch of severance optics and design. It’s not just about looking "cool" or "retro." It is a psychological trap. When Ben Stiller and production designer Jeremy Hindle set out to build the world of Lumon Industries, they weren't just making a TV set. They were building a physical manifestation of a fractured mind.

Honestly, it’s terrifying.

The show’s visual language relies on a very particular type of discomfort called "liminal space." You know that feeling when you're in an empty airport at 3:00 AM? Or a school hallway during summer break? It feels wrong. It feels like the world ended and nobody told you. In Severance, this isn't an accident; it's the core architecture of the story.

The Brutalist Bone Structure of Lumon

Everything starts with the building. The exterior of Lumon is actually the Bell Labs Holmdel Complex in New Jersey. Designed by Eero Saarinen in the late 1950s, it is a masterpiece of modernist architecture. It’s a massive, glass-walled mirror that reflects nothing but the sky and the trees, hiding the thousands of people working inside. It’s perfect. It represents the ultimate corporate contradiction: total transparency that reveals absolutely nothing.

Inside, things get weirder.

The "severed" floor isn't just an office. It is a labyrinth. Hindle and his team opted for a layout that defies logic. The hallways are too long. The angles are slightly off. If you’ve ever felt like your own office was a maze designed to keep you from leaving, Severance takes that anxiety and turns the volume up to eleven. The lighting is perhaps the most aggressive part of the severance optics and design strategy. It’s all overhead, fluorescent, and shadowless. In the real world, shadows give us a sense of depth and time. At Lumon, there is no time. There is only the "now."

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The 1970s Future

Why does the tech look like that? You’ve got these bulky, heavy-duty monitors with rounded corners and trackballs. They look like something from 1982, but they function with a complexity that feels futuristic. This is "retro-futurism," but with a corporate, mid-century twist.

The goal was to strip away any sense of "when." If the characters had iPhones, we’d know it was 2024. If they had typewriters, we’d know it was 1960. By mixing a 1970s aesthetic with advanced biotech concepts, the designers created a "non-time." This is a crucial part of the severance experience. If you don't know what year it is, you lose your connection to history. You become a blank slate.

The color palette is equally restrictive. You see a lot of "Lumon Green." It’s a seafoam-adjacent color that feels clinical but also vaguely organic, like a pond that’s been treated with too many chemicals. It’s contrasted with the stark whites of the hallways and the deep, wood-paneled walls of the executive suite. It’s a visual hierarchy. The workers get the plastic and the fluorescent lights; the bosses get the mahogany and the warmth.

How Layout Dictates Behavior

Design is never just about looks. It’s about control. In the Macrodata Refinement (MDR) office, the four desks are clustered together in the middle of a massive, empty room. Why? Because it forces the employees to focus on each other and their screens. There is no perimeter. There are no windows.

If you put people in a giant box, they start to act like lab rats.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The desk dividers are low enough that you can see your coworkers but high enough to feel like you’re in a private cubicle. It’s a half-measure of privacy that actually increases surveillance. You’re always being watched, even when you think you’re alone. This is a classic concept in architectural theory called the Panopticon. Developed by Jeremy Bentham, it’s a design for a prison where a single watchman can observe all inmates without them knowing if they are being watched. Lumon is just a Panopticon with a better dental plan.

The Significance of the Waffle Party and Aesthetics

We have to talk about the aesthetics of the "perks." The Waffle Party, the Music Dance Experience, the finger traps. These items are intentionally pathetic. They look like they were designed by someone who has heard of "fun" but never actually experienced it.

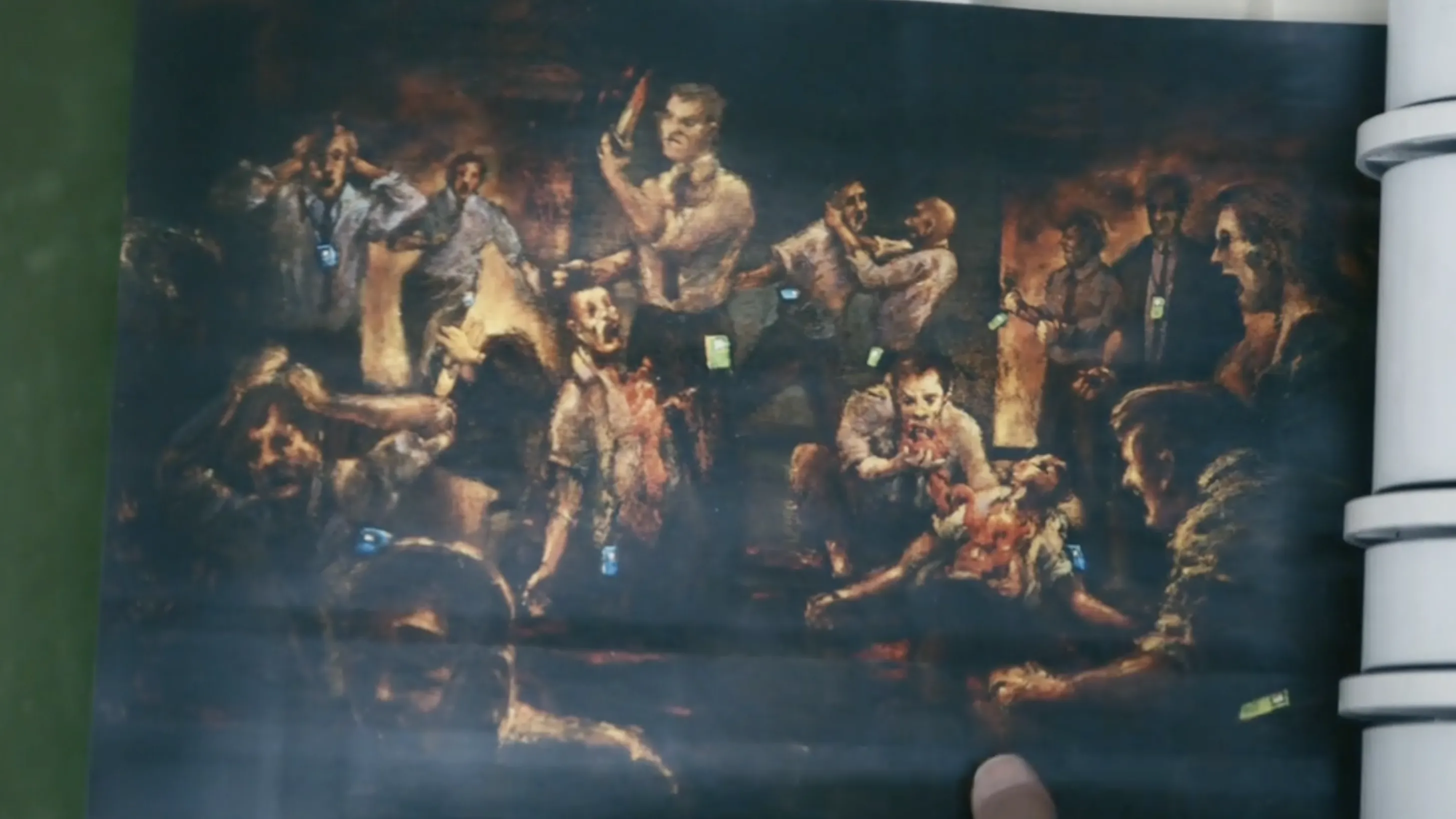

The "Optics and Design" department within the show (O&D) is literally responsible for the art on the walls. This is a meta-commentary on severance optics and design. The department spends its time creating propaganda paintings that depict the company's founders in heroic, religious poses. It’s kitsch, but it’s dangerous kitsch. It uses the visual language of the Renaissance to justify corporate slavery.

The art is meant to be confusing. One day it’s a painting of a massacre; the next, it’s a peaceful landscape. This keeps the employees in a state of perpetual emotional instability. If the environment around you is constantly shifting or presenting contradictory messages, you stop trusting your own eyes. You start trusting the company.

The Psychological Impact of "Flatness"

Most modern offices try to bring the "outside in." Think of Google’s offices with indoor trees and beanbag chairs. Lumon does the opposite. It aggressively shuts the world out. There are no textures that feel natural. Everything is laminate, metal, or low-pile carpet.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

This "flatness" is a design choice meant to mirror the "Innies'" lack of life experience. They have no memories of the sun, the wind, or the dirt. Their entire sensory world is what Lumon provides. When Helly R. looks at the ceiling tiles, she isn't just looking at a building material; she’s looking at the sky.

The costume design by Kasia Walicka-Maimone follows this same "flat" logic. The suits are ill-fitting in a way that feels intentional. They aren't fashionable; they are uniforms. The colors are muted—grays, blues, and blacks. It’s an erasure of individuality. When everyone looks like a background character, nobody feels like a hero.

Lessons for Real-World Design

So, what can we actually learn from this? Most of us don't work at a mysterious biotech firm that splits our brains in half, but we do live in a world where "work-life balance" is a buzzword that usually means "work more."

The severance optics and design serves as a warning. It shows us how environment shapes identity. If you work in a space that feels dehumanizing, you will eventually feel dehumanized.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Space

If you want to avoid the "Lumon effect" in your own life or office, you have to actively fight against the visual cues of severance.

- Introduce "Chaos" Textures: Use natural materials. Wood, stone, and linen have irregular patterns that the human brain finds soothing. Lumon is all about perfect, repetitive lines. Break those lines.

- Variable Lighting is Key: Fluorescent lights are the enemy of the circadian rhythm. If you can, use lamps with warm bulbs (2700K to 3000K) and try to get as much natural light as possible. Shadows are good. They tell your brain what time it is.

- Avoid the "Middle of the Room" Trap: If you're setting up a home office, don't put your desk in the center facing a wall. It creates a sense of vulnerability. Try the "command position"—desk facing the door with a solid wall behind you. It’s an ancient Feng Shui principle that actually lowers cortisol.

- Personalize Beyond the "Perk": Lumon gives employees "meaningless" objects. To combat this, surround yourself with things that have a history. A rock from a beach trip, a photo of a friend, a book with dog-eared pages. These are "anchors" to your "Outie" self.

- The Power of the Window: Never underestimate the psychological necessity of a horizon line. Being able to see something far away prevents the "box effect" that drives the characters in the show toward madness.

The design of Severance is a masterclass in how to make a beautiful space feel like a nightmare. By understanding the tricks they used—the liminality, the lack of shadows, the non-time tech—we can better understand how our own environments affect our mental health. Your office might not have a "Break Room" where you're forced to apologize a thousand times, but if the lighting is bad and the walls are gray, it might be doing more damage than you think.