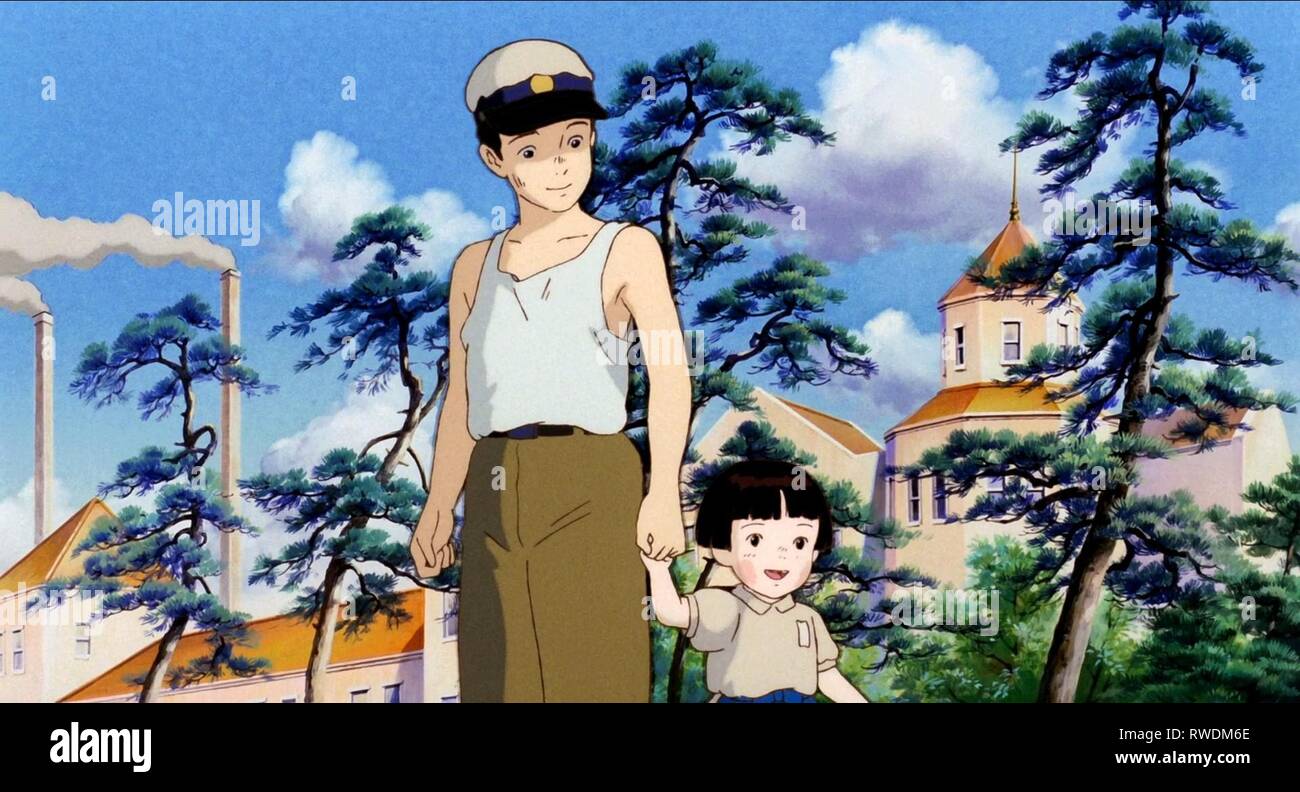

If you've seen Grave of the Fireflies, you probably remember the fruit drops. You remember the sound of that tin shaking. And you definitely remember Setsuko, the four-year-old girl whose face basically became the universal symbol for the collateral damage of war.

It's been decades since Isao Takahata released this Studio Ghibli masterpiece in 1988. Yet, every time a clip of Setsuko appears on social media, the comments section turns into a digital wake. People aren't just sad; they’re haunted. Honestly, there’s a reason for that. Setsuko isn't just a character. She’s a mirror for a very specific, very real kind of historical guilt that most people don't fully understand.

The Real Setsuko: A Story of Guilt, Not Just Sadness

Most fans know the movie is based on a semi-autobiographical short story by Akiyuki Nosaka. But the reality behind the fiction is actually much darker.

Nosaka wrote the story in 1967 as a literal apology letter to his little sister, Keiko. In the movie, Seita is an idealized version of a big brother. He’s selfless. He tries his best. He gives Setsuko everything. But the real-life Nosaka? He admitted that he wasn't always that kind.

Hunger does terrible things to people. In real life, Nosaka confessed to eating food that was meant for his sister. He even admitted to hitting her when she wouldn't stop crying from hunger. When she finally died of malnutrition in 1945, the guilt didn't go away. It fermented.

Grave of the Fireflies was his way of giving his sister the "perfect" brother he couldn't be during the war. When you watch Setsuko laugh at the fireflies or suck on a marble because she thinks it’s a candy, you’re watching a man try to rewrite his own history. It’s a ghost story, basically.

👉 See also: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

What Actually Happened to Setsuko?

In the film, Setsuko’s decline is slow and agonizing. It’s not a bomb that kills her. It’s the "dry" death of systemic failure.

The Medical Reality of Malnutrition

Setsuko dies from malnutrition and enteritis. You see the red rash on her back. That’s not just a random skin condition; it’s a symptom of her body literally consuming itself because of a lack of protein and vitamins.

When Seita takes her to the doctor, the scene is infuriating. The doctor gives a diagnosis: "malnutrition." That’s it. No medicine. No food. No help. In 1945 Japan, there was no "cure" for starvation other than food, and the state had decided that children weren't the priority for rations.

The Symbolism of the Sakuma Drops

The fruit drops—specifically Sakuma Drops—are a real Japanese candy that has existed since the Meiji era. In the movie, they represent the last shred of Setsuko’s childhood.

When the tin runs out, Seita puts water in it to get the last bit of sugar. Eventually, he fills it with her ashes. It’s one of the most brutal visual metaphors in cinema. It’s the transition from life/sweetness to death/dust.

✨ Don't miss: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Why Do We Still Blame Seita?

There is a huge divide in how people view the siblings' choice to leave their aunt’s house.

- The Western Perspective: Most Western viewers see the aunt as a villain. She’s cruel, she steals their mother’s kimonos for rice, and she begrudges a four-year-old every bite of food. From this view, Seita is a hero for protecting Setsuko's spirit.

- The Japanese Perspective: When the film was released, many Japanese critics and older audience members actually blamed Seita. They saw his "pride" as the reason Setsuko died. In a time of war, you swallow your pride. You endure the insults. You stay in the house where there is a roof and a kitchen.

Director Isao Takahata actually leaned toward the latter. He didn't see Seita as a simple hero. He saw him as a "modern" boy—someone who wanted his own world and his own way—who failed to realize that in 1945, independence was a death sentence.

The Firefly Metaphor Explained

The title Hotaru no Haka is deeper than it looks. In Japanese, "hotaru" can be written with characters that imply "fire-dropping," a reference to the incendiary bombs (M-69) that rained down on Kobe.

Setsuko asks the big question: "Why do fireflies have to die so soon?"

She’s talking about the insects she buried, but she’s also talking about herself. The fireflies are a metaphor for:

🔗 Read more: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

- The Children: Fragile, glowing briefly, then gone.

- The Kamikaze Pilots: Young men sent to burn out in a flash of "glory."

- The Bombs: The "lights" in the sky that brought the end of their world.

Setsuko’s Legacy in Modern Culture

Even in 2026, Setsuko remains a touchstone for anti-war sentiment. Unlike many war movies that focus on soldiers and strategy, this story focuses on a girl who just wants to play with a doll and eat a piece of fruit.

She represents the "Victim Consciousness" (higai-moshiki) often discussed in Japanese history. It’s the idea of focusing on the suffering of the Japanese people during the war to avoid talking about the atrocities committed by the military. While the film has been criticized for this, Setsuko’s personal tragedy is so visceral that it usually transcends politics. You can't look at her and see a "political statement." You just see a dying child.

How to Process "Grave of the Fireflies" Today

If you’re planning to rewatch or are introducing someone to Setsuko's story, keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Research the Kobe Air Raids: Knowing the historical scale—over 8,000 dead in a single night—makes the siblings' isolation feel even more terrifying.

- Watch the Opening Carefully: The movie starts with Seita’s death. You already know how it ends. This isn't a "spoiler"; it’s a narrative device to make you focus on how they lived, rather than hoping they survive.

- Compare to the Book: If you can find a translation of Nosaka’s short story, read it. It’s much shorter and significantly more bitter.

- Look for the "Ghost" Frames: Throughout the film, there are scenes where the red-tinted ghosts of Seita and Setsuko are watching their past selves. It changes the entire perspective from a linear tragedy to a cycle of eternal reflection.

The next time you see a tin of Sakuma Drops, you'll probably think of Setsuko. That’s the power of the character. She didn't change the world, and she didn't win the war. She just died. And in her simple, quiet death, she reminds us that the "glory" of history is usually built on the graves of people who never wanted anything but a piece of candy.