If you were born abroad to a U.S. citizen father and a non-citizen mother in the 1960s, your entire life path might have been decided by a matter of days. That sounds like a dramatic exaggeration, right? It isn't. For Luis Ramón Morales-Santana, those days were the difference between being a "natural-born" American and a "deportable alien."

The legal battle that followed, known as Sessions v. Morales-Santana, is one of the most bittersweet victories in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. It’s a story about old-school sexism, a legendary justice’s final stand against gender stereotypes, and a "remedy" that basically left the winner with nothing.

The Law That Stuck in the 1940s

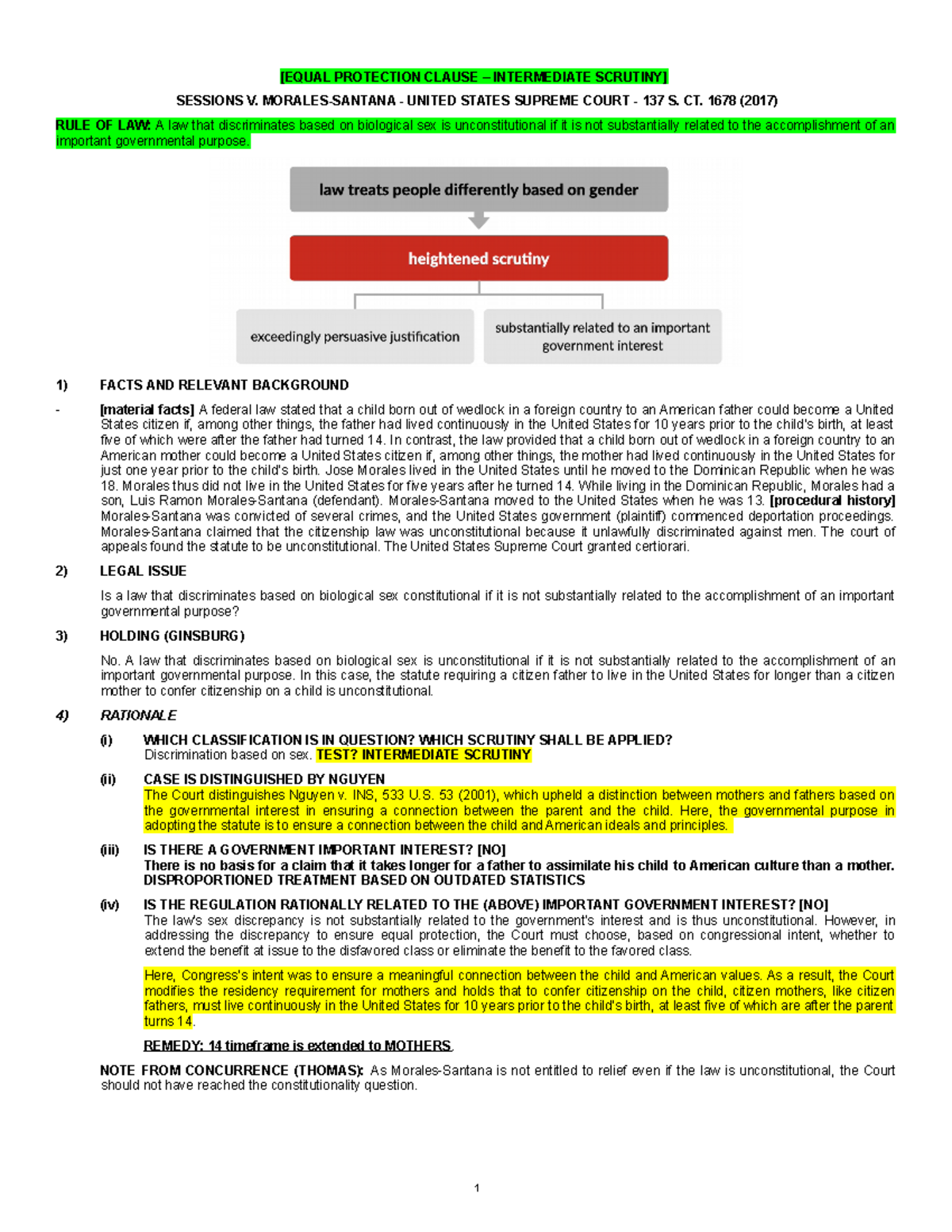

To understand why this case happened, we have to look at the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Back in the day, the law made it way easier for an unwed American mother to pass her citizenship to her kid than for an unwed American father.

If a mom was a U.S. citizen, she only had to live in the States for one continuous year before the birth. That’s it. One year.

But if the father was the American citizen? He had to prove he’d been physically present in the U.S. for ten years, five of which had to be after he turned 14.

This was the law in 1962 when Morales-Santana was born in the Dominican Republic. His dad was a U.S. citizen. His mom wasn't. His dad had lived in Puerto Rico (U.S. territory) for most of his life, but he moved to the Dominican Republic just 20 days before his 19th birthday.

🔗 Read more: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Think about that. Because he was 20 days short of that "five years after age 14" requirement, he couldn't pass his citizenship to his son.

Why the Double Standard?

Honestly, the government’s reasoning was pretty cringey by modern standards. When Sessions v. Morales-Santana reached the high court, the government argued that these rules were meant to ensure the kid had a "sufficient connection" to the U.S.

They also claimed it was about preventing "statelessness"—basically making sure a kid didn't end up with no country at all. But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg saw right through that.

She pointed out that the law was actually built on "overbroad generalizations." Specifically, the 1940s-era assumption that an unwed mother is the "natural and sole guardian" of a child, while the father is just... well, irrelevant. The law assumed mothers would stay with the kid and fathers would just vanish.

Ginsburg, who spent her whole career fighting these kinds of "man is the breadwinner, woman is the caregiver" tropes, wasn't having it.

💡 You might also like: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

The "Mean Remedy" That Changed Everything

In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled 6-2 that this gender-based distinction was unconstitutional. It violated the Equal Protection Clause. Huge win for equality, right?

Well, kinda.

Usually, when a law is found to be discriminatory because it gives one group a benefit (mothers) and denies it to another (fathers), the Court "levels up." They give the benefit to everyone.

But in Sessions v. Morales-Santana, the Court did the opposite. They "leveled down."

Instead of giving fathers the easy one-year requirement, they took it away from the mothers. They decided that from now on, everyone—moms and dads alike—would have to meet the tougher five-year residency requirement (the law had been updated since 1962 from ten years to five).

📖 Related: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

For Luis Morales-Santana, this was a disaster. He won the argument that the law was sexist, but because the Court "fixed" the law by making it harder for everyone, he still didn't qualify for citizenship. He won the battle and lost the war.

Why This Case Still Matters in 2026

You might wonder why we’re still talking about a 2017 ruling. It's because this case fundamentally changed how the government handles derivative citizenship. It also serves as a warning about how "equality" doesn't always mean "more rights."

Key Takeaways from the Ruling:

- Gender stereotypes are dead in immigration law. The government can no longer justify laws based on the idea that mothers are "more natural" parents than fathers.

- The "Leveling Down" Precedent. This case is a huge citation for whenever courts find a law unconstitutional but decide to fix it by taking a benefit away from everyone rather than giving it to the excluded group.

- Congress holds the ultimate power. The Court basically told Congress, "We broke the old sexist rule, now you go write a better one."

It’s a complicated legacy. On one hand, it's a landmark for gender equality. On the other, it left a lot of people who were counting on that one-year mother’s rule in a very tough spot.

What You Can Do Now

If you or someone you know is dealing with a derivative citizenship claim—meaning citizenship passed down from a parent—the rules are tighter than they used to be.

- Check the Dates. The law that applies to you is usually the law that was in effect the year you were born. This gets incredibly messy because the INA has changed multiple times (1934, 1940, 1952, 1986).

- Gather Evidence Early. Physical presence is the hardest thing to prove. You need school records, employment history, or tax returns from the parent to show they were actually in the U.S. for the required time.

- Consult a Specialist. Don't just rely on a DIY Google search for this. Derivative citizenship is one of the most complex niches in immigration law.

The era of "easier" paths for unwed mothers is over. Thanks to Sessions v. Morales-Santana, the playing field is level, but the hurdle is higher for everyone.

Next Steps: You should review your parents' entry and exit records if you are planning to file an N-600 (Application for Certificate of Citizenship). Having those dates exactly right—down to the day—is often the only thing that matters in the eyes of USCIS.