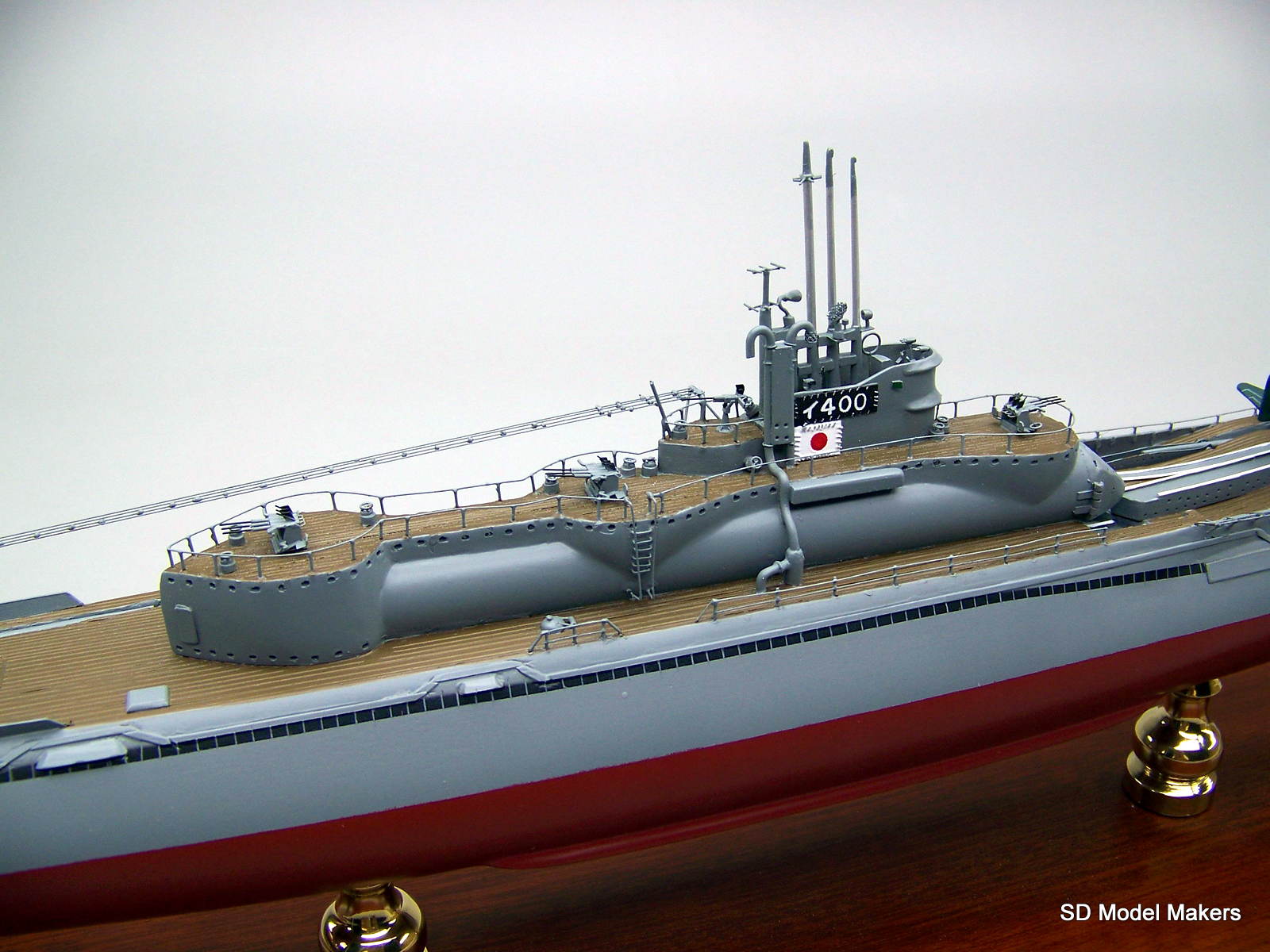

Imagine a submarine longer than a football field, lurking off the coast of New York in 1945, ready to launch a squadron of bombers. It sounds like something out of a mid-budget sci-fi flick or a Tom Clancy fever dream. But the Sen Toku I 400 class submarine was very real, very lethal, and almost changed the course of World War II. Honestly, it’s one of those pieces of history that feels fake because the scale is just so ridiculous for the time.

Most people think of World War II subs as cramped, oily metal tubes like the German U-boats or the American Gato-class. Those were tiny. The I-400, however, was a monster. It was the largest submarine ever built before the nuclear age arrived in the 1960s. We’re talking about a vessel that could carry enough fuel to go around the world one and a half times without stopping. That’s 37,500 nautical miles. It’s a range that still makes modern diesel-electric sub designers do a double-take.

The Underwater Aircraft Carrier Concept

The whole idea came from the mind of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. Yeah, the same guy who planned the Pearl Harbor attack. He realized that Japan couldn't win a traditional war of attrition against the U.S. industrial machine. He needed a "Silver Bullet." His solution? A submarine that was actually an aircraft carrier.

These weren't just "scout" planes like other subs carried. The Sen Toku I 400 class submarine was designed to house three Aichi M6A1 Seiran bombers. These planes were specifically built to fold up—wings, tail, and all—into a 115-foot-long cylindrical hangar on the deck.

How it actually worked

Once the sub surfaced, a well-trained crew could pull those planes out, snap the wings into place, and launch them off a 120-foot compressed-air catapult in under 45 minutes. That is fast. If they didn't bother with the pontoons for landing, they could do it even quicker. The pilots knew that without pontoons, they'd have to ditch in the ocean and hope the sub found them. It was basically a one-way ticket for the aircraft.

👉 See also: How to Mute Google Maps: Getting Some Peace on Your Next Drive

The I-400 wasn't just big; it was weirdly shaped. If you looked at a cross-section of the hull, it looked like a figure-eight. This was because the engineers had to weld two pressure hulls together side-by-side to provide enough stability to hold that massive hangar on top without the whole thing tipping over in a stiff breeze. Even with that, the conning tower had to be offset to the port side to keep the center of gravity from going haywire.

Mission: The Panama Canal

The original plan was terrifyingly ambitious. The Japanese High Command wanted to send a fleet of these "Sen Toku" (Special Submarine) boats to the Panama Canal. The goal was to blow up the Gatun Locks. Why? Because if you take out the locks, you cut the "umbilical cord" between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The U.S. Navy would have had to sail all the way around South America to get reinforcements to the Pacific theater.

It never happened.

By the time the I-400 and its sister, the I-401, were actually ready for action in late 1945, the war was already lost. The mission changed from Panama to a strike on the U.S. carrier fleet at Ulithi Atoll. But even that was a bust. While the subs were en route, Japan surrendered. The crews were ordered to destroy their secret weapons. They ended up launching the Seirans into the ocean—engines running, no pilots—just to make sure the Americans didn't get their hands on the tech.

👉 See also: Wait, Can You Still Send Money With Snapchat? The Reality of Snapcash and Modern Alternatives

Why the US Navy Scuttled Them

When the U.S. Navy finally boarded the I-400, they were stunned. They found a sub that was twice the size of anything they owned. It had a rubberized coating on the hull to absorb sonar waves—early stealth tech! It also had a snorkel system that allowed it to run its diesel engines while submerged.

But then the Soviets started asking questions.

The Cold War was already simmering, and the U.S. didn't want the USSR to get a look at this advanced Japanese engineering. Under the terms of the occupation, all captured technology was supposed to be shared. To avoid this, the U.S. Navy took the I-400 and I-401 out near Oahu in 1946, used them as target practice for torpedoes, and sent them to the bottom of the Pacific.

📖 Related: Facebook Customer Care Telephone Number: What Most People Get Wrong

They stayed lost for decades. It wasn't until 2013 that researchers from the University of Hawaii found the wreck of the I-400 in over 2,000 feet of water. The hangar and the conning tower had been ripped off during the descent, but the massive hull was still there, a ghost of a war that almost went very differently.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're looking to dive deeper into the technical reality of the Sen Toku I 400 class submarine, there are a few things you can actually do rather than just reading Wikipedia:

- Visit the Kure Maritime Museum: If you ever find yourself in Japan, the "Yamato Museum" in Kure has incredible scale models and technical drawings that show exactly how the "figure-eight" hull was constructed.

- Check the NOAA Archives: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has released high-definition sonar maps and ROV footage of the I-400 wreck site off Hawaii. It's the best way to see the "stealth" coating and the catapult system as they look today.

- Read "Operation Storm" by John Geoghegan: This is widely considered the definitive book on the I-400. It uses translated Japanese logs and interviews with surviving crew members to explain why the Panama Canal mission was scrubbed.

- Analyze the Seiran: Look up the Aichi M6A1 at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center. It’s the only surviving Seiran in the world. Seeing the folding wing mechanism in person makes you realize just how tight the tolerances were inside that submarine hangar.

The I-400 wasn't just a big boat. It was a bridge between the old-school naval warfare of the 19th century and the strategic missile submarines of today. It proved that a sub could be a mobile strike platform, a lesson the world wouldn't forget.