Nature is weird. Honestly, if you didn’t know any better and someone showed you a picture of a fat, multi-legged worm and then a vibrant, winged insect, you’d probably think they were from different planets. But that’s the magic of metamorphosis. When people search for pics of life cycle of butterfly, they usually want more than just a biology textbook diagram. They want to see the grit, the slime, and the eventual gold of one of the most drastic physical changes on Earth. It’s a process that is as violent as it is beautiful.

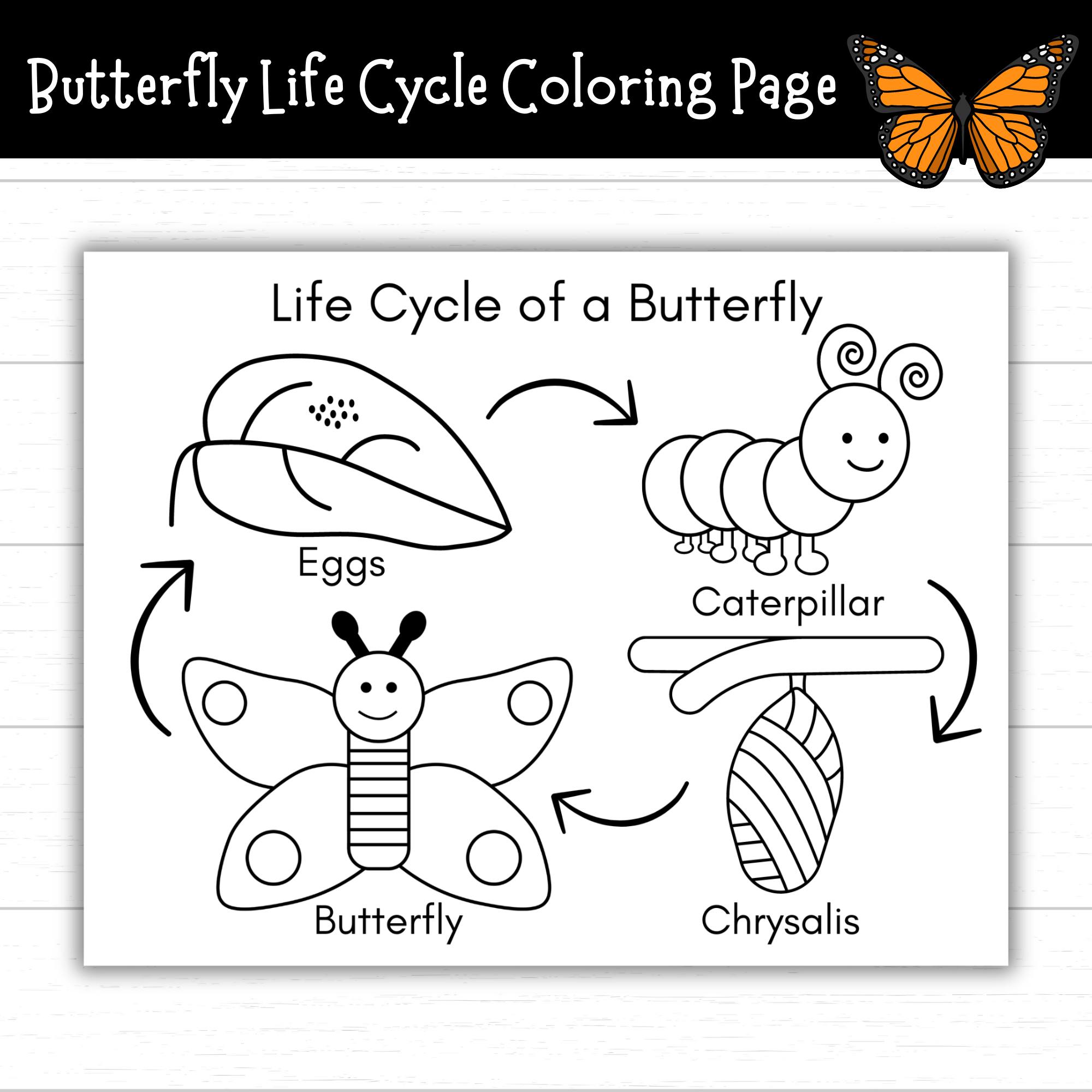

Most of us learned the four stages in elementary school: egg, larva, pupa, adult. Simple, right? Not really. Real life is way messier. You’ve got caterpillars that look like bird poop to avoid being eaten and chrysalises that literally liquefy their contents before rebuilding a brain and wings from scratch.

The Egg Stage: More Than Just a Speck

It all starts with a tiny dot. If you look at high-definition pics of life cycle of butterfly eggs, you’ll notice they aren't just smooth white orbs. They have textures. Some look like microscopic corn on the cob; others look like intricate, ribbed vases. A female butterfly doesn't just drop these anywhere. She is incredibly picky. She uses sensors on her feet to "taste" the leaves, ensuring she’s found the specific host plant her babies can actually eat. For a Monarch, that’s milkweed. for a Black Swallowtail, it might be parsley or dill.

The egg stage usually lasts about three to seven days. It's a race against time. Predators like ants and spiders are always on the hunt. Inside that tiny shell, a heartbeat begins. When the larva is ready, it doesn't just hatch; it eats its way out.

And then? It eats the shell.

Waste not, want not. That shell is packed with protein, and the tiny "cat" needs every bit of energy for the growth spurt that’s about to happen.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The Larva: The Eating Machine

This is the stage everyone recognizes, but it's also the most vulnerable. A caterpillar’s sole job is to eat. They are essentially a walking stomach with sixteen legs. They can grow to 100 times their original size in just a few weeks. Imagine a human baby growing to the size of a school bus in a month. That’s the scale we’re talking about here.

Because their skin (exoskeleton) doesn’t stretch, they have to shed it. This is called molting. They go through five of these stages, known as "instars."

- First Instar: Tiny, almost transparent, and incredibly fragile.

- Third Instar: Starting to show distinct colors and patterns.

- Fifth Instar: The big one. This is when the caterpillar is at its most photogenic and most likely to be featured in pics of life cycle of butterfly galleries.

You might notice some caterpillars have "horns" or "hairs." Take the Monarch caterpillar—those black tentacles aren't stingers; they're sensory organs. Or look at the Spicebush Swallowtail. It has giant fake eyespots on its back to trick birds into thinking it's a snake. Evolution is basically the world's best costume designer.

The Pupa: The Great Liquefaction

This is where things get truly sci-fi. When the caterpillar is full, it wanders off. It’s looking for a safe spot. It spins a silk button, hangs upside down in a "J" shape, and sheds its skin one last time. Underneath is the chrysalis.

Common misconception: a chrysalis and a cocoon are the same thing. They aren't. Butterflies make a chrysalis (a hard skin), while moths spin a cocoon (made of silk).

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Inside that shell? Chaos.

The caterpillar's body basically dissolves. Enzymes break down the tissues until it's a literal soup of cells. However, certain clusters of cells called "imaginal discs" survive. These discs were always there, even inside the egg, just waiting for this moment. They act as the blueprints for the wings, the legs, and the proboscis.

If you look at time-lapse pics of life cycle of butterfly transitions, you can sometimes see the wings beginning to show through the chrysalis wall right before it hatches. It turns clear. You’re literally looking at a ghost of the creature it’s about to become.

Emergence and the First Flight

The moment of "eclosion" (the fancy word for hatching) happens fast. The chrysalis splits, and the butterfly crawls out. But it looks terrible. Its wings are tiny, wet, and shriveled. It looks like a mistake.

The butterfly has to pump fluid from its swollen abdomen into the veins of its wings. This is a critical moment. If it falls or if the wings don't expand properly, it will never fly, and it will likely die. It takes about an hour for the wings to harden. During this time, the butterfly is a sitting duck for predators. It’s also during this stage that they expel "meconium," which is a reddish liquid that often gets mistaken for blood. It’s actually just waste left over from the transformation.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Why We Care About the Imagery

Seeing these stages through photography does something for us. It’s not just about "pretty bugs." It’s about survival. When you see a high-res photo of a Monarch's wings, you see the scales. Butterflies belong to the order Lepidoptera, which literally means "scale wing." Each of those tiny scales is like a pixel on a TV screen, creating the colors and patterns that help them find mates or hide from birds.

Researchers like those at the Xerces Society or the Monarch Watch program rely on these visual identifiers to track population health. If caterpillars are small or chrysalises are turning black prematurely, it signals disease or environmental stress.

How to Witness This Yourself

If you want to capture your own pics of life cycle of butterfly, you don't need a lab. You just need a garden.

- Plant the Host: You can't have butterflies without the specific plants their caterpillars eat. Plant Milkweed for Monarchs, Pipevine for Pipevine Swallowtails, or Fennel for Black Swallowtails.

- Stop the Sprays: Pesticides don't discriminate. If you kill the "pests," you're killing the butterflies too.

- Observation: Look under leaves. That’s where the eggs are hiding.

- Macro Lens: Even a cheap macro attachment for a smartphone can reveal the incredible textures of an egg or the tiny "feet" (prolegs) of a caterpillar.

Real-World Insights for the Backyard Naturalist

A lot of people think they’re helping by bringing caterpillars inside. While it’s fun to watch, research from the University of Georgia has shown that indoor-raised Monarchs sometimes have trouble with migration because they aren't exposed to natural light cycles and temperatures. If you do raise them to get those perfect photos, keep them in a mesh enclosure on a porch where they can still feel the "real" world.

The cycle is a circle, not a line. The adult butterfly lives for a few weeks (or months if it’s a migrating generation), finds a mate, and the whole frantic, beautiful, messy process starts all over again.

Actionable Steps for Your Butterfly Journey

- Identify Your Local Species: Check the Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) database to see what’s flying in your zip code right now.

- Audit Your Garden: Ensure you have "nectar plants" (for adults to eat) and "host plants" (for babies to eat). Most people only provide the nectar, which is like having a restaurant but no nursery.

- Contribute to Science: Upload your photos to iNaturalist. Your casual backyard snaps help scientists track migration patterns and the effects of climate change on emergence dates.

- Timing Your Photos: The best light for photographing these stages is early morning. Butterflies are ectothermic (cold-blooded), so they are sluggish when it's cool, making them much easier to photograph before the sun hits its peak.