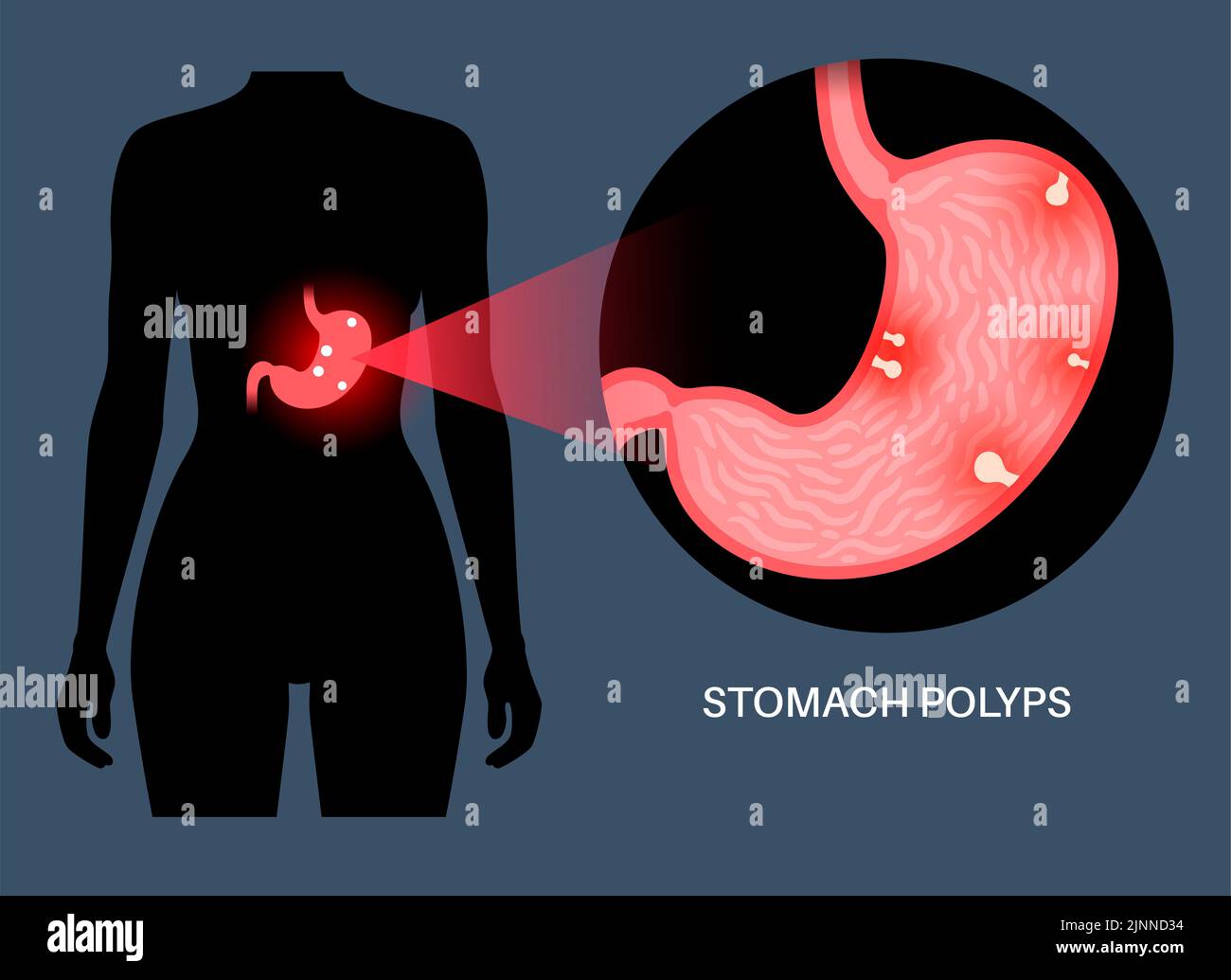

You’re sitting in a cold exam room, maybe still feeling a bit groggy from the sedation, and your gastroenterologist hands you a glossy printout. On it are several grainy, pinkish-red circles that look like tiny mushrooms or skin tags growing inside a cavernous, wet tunnel. These are pictures of stomach polyps, and for most people, seeing them for the first time is deeply unsettling.

It’s scary.

Your mind immediately jumps to the worst-case scenario. Cancer. But honestly? Most of the time, these little growths are incidental findings. They’re like the moles of the digestive tract. You went in because of persistent acid reflux or maybe some vague upper abdominal pain, and the endoscope caught these hitchhikers on camera.

Understanding what those images actually show requires a bit of a shift in perspective because, in the world of endoscopy, color and texture tell a much bigger story than just the presence of a "bump."

The Visual Language of Gastric Polyps

When you look at pictures of stomach polyps from a gastroscopy, you’re seeing a view captured by a high-definition camera at the end of a flexible tube. Doctors aren't just looking for "blobs." They are looking at the "pit pattern" and the vascularity—the way blood vessels wrap around the growth.

Fundic gland polyps are the most common. They usually look like small, smooth, sessile (flat-based) mounds. They’re often the same color as the surrounding stomach lining or perhaps a slightly paler pink. If you see a picture where the polyps look like a field of tiny bubbles, those are often the result of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole or pantoprazole. It's a weird side effect of modern medicine. The stomach's parietal cells get blocked, the body tries to compensate, and you get these benign little cysts.

Hyperplastic polyps look different. They tend to be redder. More angry.

🔗 Read more: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

Because they often form in response to chronic inflammation—think H. pylori infections or long-term gastritis—they look inflamed. They might have a "strawberry" appearance. In a photo, a hyperplastic polyp might show some white exudate (basically a scab) if it’s been irritated by stomach acid.

Then there are adenomatous polyps. These are the ones that make doctors lean in closer. They are less common but carry a higher risk of turning into something nasty. Visually, they often appear more "velvety" or lobulated. They don't look like smooth bubbles; they look more like a cauliflower.

Why the Camera Doesn't Tell the Whole Story

You can’t diagnose a polyp just by looking at a photo. You just can't.

A doctor might see a 5mm growth and think it looks "textbook benign," but the gold standard is always the biopsy. During the procedure, the doctor slides a tiny wire snare or forceps through the scope and snips the polyp off.

It doesn't hurt. The stomach lining doesn't have pain receptors in that way.

The pathology report is where the real answers live. Dr. Mark Pochapin, a well-known gastroenterologist, often emphasizes that the visual appearance is just the first clue in a much longer detective story. While a picture might show a "sessile serrated lesion," the microscope reveals the cellular architecture that determines if that growth was ever going to become a threat.

💡 You might also like: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

Real-World Variations You Might See

If you're scouring the internet for pictures of stomach polyps to compare to your own, keep in mind that lighting and the quality of the scope matter immensely.

- NBI (Narrow Band Imaging): Some photos look blue or green. This isn't because your stomach is alien; it's a special light filter that highlights blood vessels. It helps doctors spot "neoplasia" (pre-cancerous changes) that might be invisible under normal white light.

- Size Comparisons: Usually, there’s a tool in the frame, like a biopsy forceps, to provide scale. A polyp might look massive on a 24-inch monitor, but in reality, it's the size of a grain of rice.

- Multiple Polyposis: Sometimes the pictures show dozens, even hundreds, of polyps. This is often seen in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP). It looks overwhelming—like a cobblestone street.

It’s also worth noting that location matters. A polyp in the "antrum" (the lower part of the stomach) is often treated with more suspicion than one in the "fundus" (the top part). The environment in the lower stomach is harsher, and the types of cells there are more prone to changing when they get irritated.

What Happens After the Photo Is Taken?

Once the doctor has the pictures of stomach polyps and the tissue samples, the waiting game begins. It usually takes 3 to 7 business days to get the pathology back.

If it’s a fundic gland polyp? Usually, nothing happens. You might be told to keep an eye on your PPI dosage, but you won't need another scope for years.

If it’s an adenoma? You’re likely looking at more frequent surveillance.

The most important thing to remember is that the discovery of polyps is actually a success. It means the screening worked. We found something before it could ever become a problem. In many ways, a "clean" photo of a polyp being removed is the best outcome you can ask for during an endoscopy.

📖 Related: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Steps for Your Next Appointment

If you have your endoscopy photos in hand, don't just file them away in a drawer.

Ask for the pathology correlation. When the biopsy results come in, ask your doctor to explain how the microscopic findings match the visual images. "Was that red one in the antrum the hyperplastic one?" This helps you understand your own anatomy and risk factors.

Inquire about H. pylori testing. Since certain polyps are driven by this bacteria, confirming your status can prevent new polyps from forming. If you have the bacteria, a simple course of antibiotics can change the entire health of your stomach lining.

Review your medication list. If your pictures showed "PPI-related" fundic gland polyps, talk to your doctor about whether you actually need to be on that acid-blocker long-term. Sometimes we stay on meds for years out of habit, and our stomachs react by growing these tiny, benign bumps.

Check your family history. If the photos showed a high "burden" of polyps (more than 20), it’s time to look at your family tree. Some stomach polyps are linked to genetic syndromes that also affect the colon.

Keep the physical copies. Electronic records are great, but having those printed pictures of stomach polyps is vital if you ever switch doctors or see a specialist. Visual changes over time—like a polyp regrowing in the same spot—are huge clinical red flags that a new doctor can only spot if they have the original baseline.

The pink bumps on the screen aren't a death sentence. They are data points. Use them to have a real, nuanced conversation with your medical team about what’s happening inside your body.