You probably remember the smell. That sharp, sulfurous tang of a freshly sliced Red Globe or yellow onion wafting through a high school biology lab. It’s a rite of passage. For most of us, peering at onion cells under microscope lenses was the first time we realized that "life" isn't just a vague concept—it’s a mechanical reality built out of tiny, rectangular bricks.

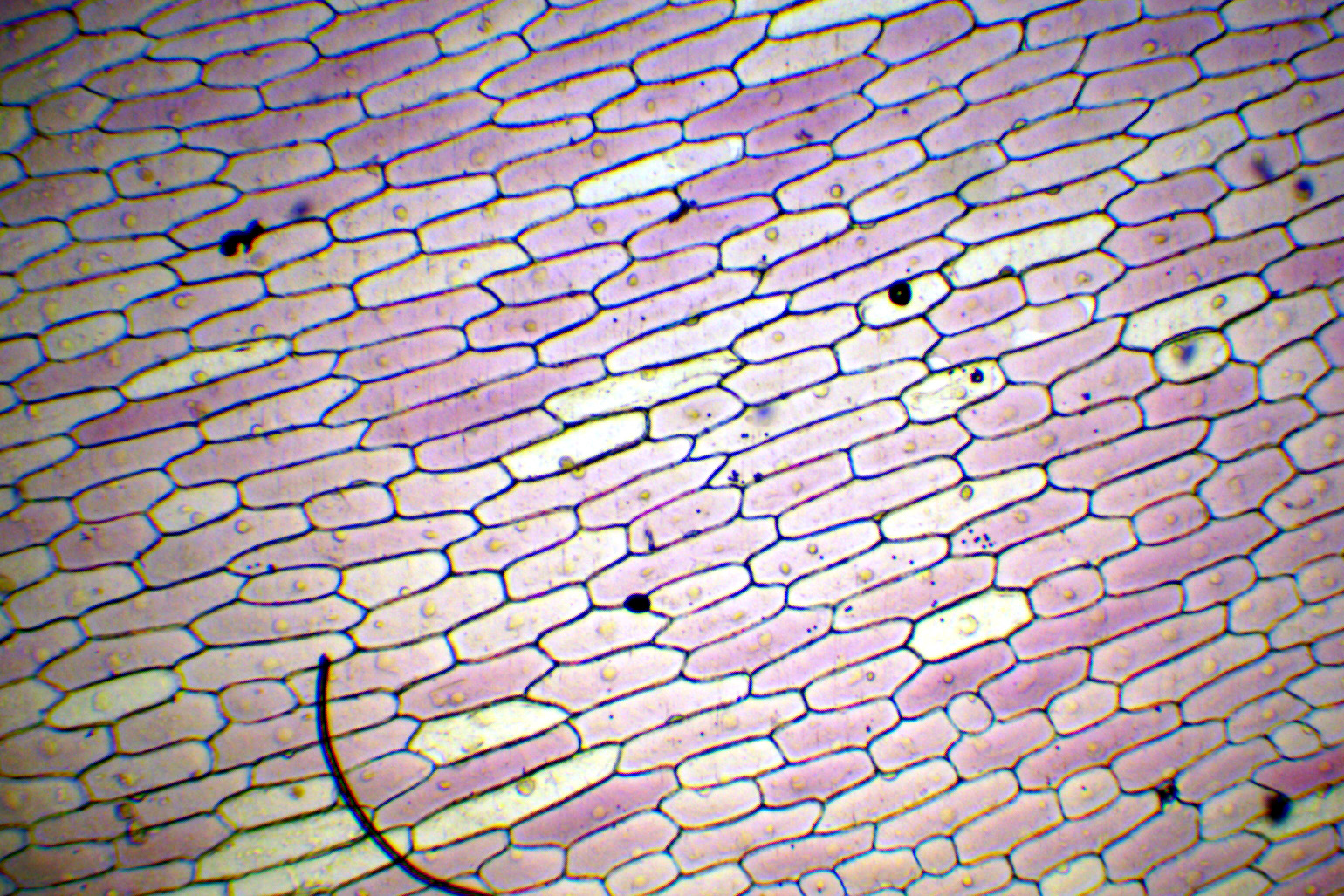

It looks like a brick wall. Seriously.

If you peel that translucent, paper-thin layer from the inner curve of an onion scale, you’re holding a single layer of biological history. It’s called the epidermis. Most people mess this up the first time. They grab a chunk of the onion "meat" and wonder why they see a blurry, white blob. You need it thin. Like, thinner than a strand of hair thin. When you get it right and drop that sliver into a bead of iodine, the magic happens. Those translucent boxes suddenly pop into view, revealing the rigid architecture of the plant world.

The Secret Architecture of the Onion Epidermis

Why onions? Why not a piece of steak or a leaf from the backyard? Honestly, it’s about simplicity and structure. Onion bulbs are actually modified leaves stored underground. Because they don't need to photosynthesize—they're busy hiding from the sun—they don't have chloroplasts. This makes them incredibly "clean" subjects. You aren't distracted by green blobs moving around. Instead, you get a clear, unobstructed view of the cell wall and the nucleus.

The cell wall is the star here. It's made of cellulose, a tough carbohydrate that gives the onion its crunch. When you look at onion cells under microscope magnification, you’re seeing the exoskeleton that allows plants to stand tall without a skeleton. These walls are fixed. Unlike animal cells, which are squishy and irregular, onion cells are surprisingly uniform. They’re elongated rectangles, mostly, packed together so tightly there’s almost no intercellular space.

It’s efficient. It’s sturdy. It’s basically nature’s version of a high-rise apartment complex.

What’s Really Inside That Tiny Box?

Once you’ve dialed in the focus, usually at 400x magnification, you’ll spot a small, dark dot pushed off to the side. That’s the nucleus. It’s the brain of the operation, containing the DNA. In an onion cell, the nucleus is often shoved against the wall by a massive central vacuole.

📖 Related: Prince Palace Truck Stop: Why This Unlikely Spot Became a Legend

Think of the vacuole as a giant water balloon taking up 90% of the room. This vacuole maintains "turgor pressure." Basically, it keeps the cell inflated. If the onion dries out, the vacuole shrinks, the pressure drops, and the onion gets soft and gross. Under the microscope, the cytoplasm—the jelly-like stuff filling the rest of the space—looks like a grainy, faint mist. If you're lucky and your microscope is high-quality, you might see cytoplasmic streaming, where the guts of the cell are slowly swirling around like a lazy river.

The Staining Game: Why Iodine is Your Best Friend

You can’t just throw a dry onion skin on a slide and expect a 4K view. It doesn’t work that way. Without a stain, onion cells are almost perfectly transparent. They’re ghosts.

Most labs use Iodine (Lugol's solution) or Methylene Blue. Iodine is the gold standard for onion cells under microscope because it reacts with the starch and proteins. It turns the nucleus a deep brown or gold and makes the cell walls look like dark outlines.

- Iodine: Best for highlighting the nucleus and general structure.

- Methylene Blue: Great if you want to see the contrast of the cytoplasm, though it’s more common for cheek cell labs.

- Plain Water: Only works if you use "darkfield" microscopy, which most hobbyists don't have.

If you use too much iodine, you’ll drown the sample. A single drop. That’s all it takes. Then you drop the coverslip at a 45-degree angle to avoid air bubbles. Air bubbles are the enemy of science. They look like perfect, thick-rimmed black circles under the lens, and beginners always mistake them for "giant mutant cells." They aren't. They’re just trapped breath.

Common Blunders Even Pros Make

I’ve seen people try to use the outer, papery skin—the brown stuff that flakes off in the grocery store bag. Don't do that. Those cells are dead. They’re desiccated husks. You want the juicy, fleshy layers underneath.

Another big mistake is light management. People crank the microscope light to the max. It blinds the sensor (or your eye) and washes out the delicate details of the cell membrane. You want to keep the light low and use the diaphragm to create shadows. It’s the shadows that give you the "3D" effect.

Also, thickness matters. If your specimen is more than one cell thick, the layers overlap. It looks like a messy gridlock. You want a "monolayer." If you can see the cells overlapping, you haven't peeled it thin enough. Try using tweezers to just "nick" the surface and pull. It should look like a piece of Scotch tape.

The Science of Why We Care

This isn't just a boring classroom exercise. Observing onion cells under microscope helped early biologists like Robert Hooke and Matthias Schleiden formulate the Cell Theory. It’s the realization that all living things are composed of these fundamental units.

In modern labs, onion cells are actually used for serious research. Because they are large and easy to manipulate, scientists use them to study how things move through cell membranes. They are also used in "plasmolysis" experiments. If you add salt water to the slide, you can actually watch the cell membrane shrivel away from the cell wall as the water is sucked out. It’s a brutal, real-time demonstration of osmosis.

It’s also a lesson in genetics. Onions have relatively large chromosomes. While you won't see them in a standard "resting" cell, if you look at the cells in the very tip of an onion root, you can catch them in the act of mitosis—cell division. You can see the DNA pulling apart like sticky taffy.

How to Do This at Home Right Now

You don't need a $2,000 lab setup to see this. A decent $100 student microscope is plenty.

- Grab a red onion (the pigment sometimes makes the cells easier to see even without stain).

- Snap a fleshy layer until it breaks, then use tweezers to peel the thin "skin" from the inner surface.

- Place it flat on a glass slide. No folds!

- Add a drop of tincture of iodine (from the first-aid aisle) or even just a drop of water.

- Lower the coverslip slowly.

- Start at the lowest power (4x) to find the edge of the tissue, then move up to 10x and 40x.

You’ll see it. That unmistakable pattern. It’s a bit humbling to realize that the onion on your burger is made of millions of these intricate, organized little rooms.

Moving Beyond the Basics

Once you've mastered the standard view, try playing with the environment. Add a drop of sugar water to one side of the coverslip and pull it through with a paper towel on the other side. Watch the cells react. It happens faster than you’d think.

The beauty of the onion cell is its reliability. It’s the "Hello World" of biology. It works every time, provided you have the patience to get a thin peel. It’s a reminder that there’s a whole universe of complexity happening at a scale we usually just ignore.

Next time you’re prepping dinner, take a second to look at that translucent film. You’re looking at the blueprint of life. If you have a digital microscope, try taking a time-lapse. While the walls don't move, the internal fluids are surprisingly busy. It’s a tiny, bustling city contained within a vegetable.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Invest in a 1000x Compound Microscope: If you really want to see the organelles like mitochondria (though they are very faint), you'll need higher magnification and better optics.

- Experiment with Vital Stains: Try using food coloring if you don't have iodine; it doesn't work as well but can highlight different structures in a pinch.

- Document the Root Tip: If you grow an onion in a jar of water, the white roots that grow out are perfect for seeing cells in the process of dividing. That’s where the real action is.

- Compare Species: Try the same process with a garlic clove or a scallion. Notice how the cell shapes change slightly even though they are closely related.