Everyone talks about Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. They mention Sacagawea. They might even mention York. But honestly, the most consistent, hardworking, and arguably bravest member of the Corps of Discovery didn't even walk on two legs. We’re talking about Seaman, the black Newfoundland dog who survived near-constant danger to reach the Pacific and back.

He wasn't just a pet. Not even close.

Lewis bought him for $20 in Pittsburgh back in 1803. That was a massive amount of money at the time—basically half a month's salary for an Army captain. But Lewis knew what he was doing. He needed a "water dog" capable of retrieving game, guarding the camp against grizzlies, and potentially acting as a diplomatic icebreaker with Indigenous tribes they’d meet along the way. Seaman did all of that and then some.

Why the Lewis and Clark expedition Seaman was a literal lifesaver

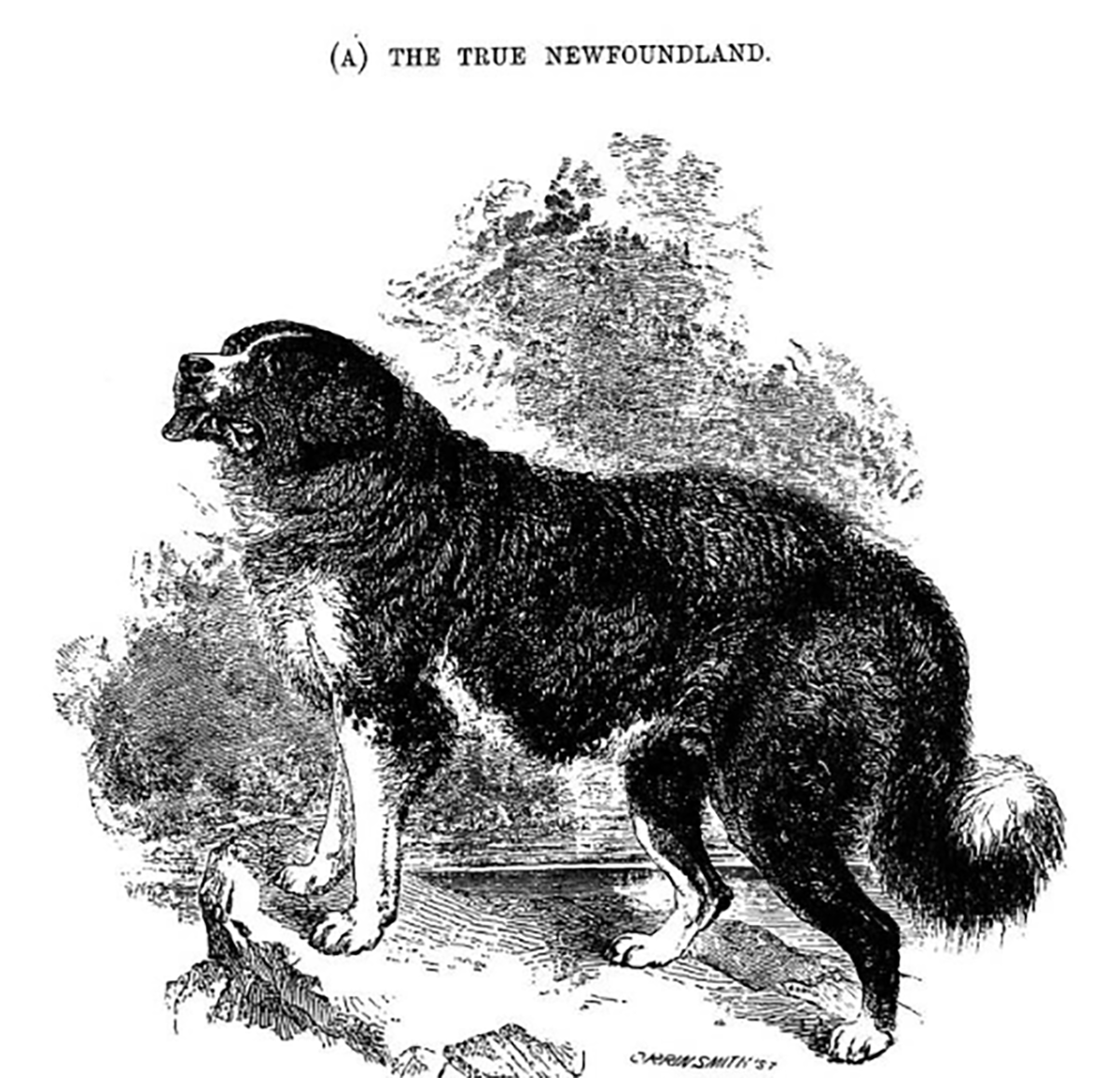

Newfoundlands are massive. They are essentially bears that like people. Lewis describes Seaman as being "very docile" but incredibly protective.

On the trail, the Lewis and Clark expedition Seaman wasn't just tagging along for the views. He worked. Hard. One of his primary jobs was hunting. In the early 1800s, feeding dozens of hungry men required constant effort. Lewis’s journals are full of praise for the dog’s ability to dive into the river and catch squirrels or bring back wounded waterfowl. It sounds funny today—a giant dog chasing squirrels—but when you're starving in the wilderness, every bit of protein matters.

Protection was the other big thing.

✨ Don't miss: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

Imagine sleeping in a thin tent or under the stars in territory where grizzly bears haven't learned to fear humans yet. The journals mention multiple instances where Seaman’s barking saved the party from disaster. One night in May 1805, a rogue buffalo charging through the camp nearly crushed the sleeping explorers. It was Seaman who went after the beast, diverting it and potentially saving Lewis or Clark from being trampled to death in their sleep.

The brutal reality of the journey

Life wasn't easy for him. The terrain was hell on his paws. Prickly pears—those nasty, spine-covered cacti—were a constant nightmare. Lewis notes that the dog’s feet were frequently bloody and torn.

Then there were the mosquitoes. People forget how bad the bugs were. Lewis wrote about how the mosquitoes were so thick they literally drove the dog "almost frantic." He’d have to bury himself in the sand or stay in the water just to find a moment of peace.

And let’s talk about the surgery.

In August 1805, Seaman was bitten by a beaver. Beavers have massive, sharp teeth, and this one sliced a major artery in the dog's leg. It was bad. Lewis, who acted as the group's unofficial doctor, had to perform emergency surgery to stop the bleeding. He stayed up with the dog, tending to the wound, terrified he was going to lose his best friend. Luckily, Seaman was tough. He pulled through.

🔗 Read more: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

The mystery of what happened after the Pacific

For a long time, historians had no idea what happened to Seaman after the party returned to St. Louis in 1806. Did he live out his days on a farm? Did he die on the trail? The journals sort of stop mentioning him toward the end, leading to a lot of sad speculation.

But here’s the cool part: we actually have a clue.

In 1814, a guy named Timothy Alden published a book about epitaphs. In it, he described a dog collar he saw in a museum in Alexandria, Virginia. The inscription on the collar said: "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacifick ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

This suggests Seaman survived the entire trip and lived with Lewis back east.

There’s a much darker theory, though. Some historians, like James J. Holmberg, found evidence suggesting that after Lewis died (likely by suicide) in 1809, Seaman was so devastated that he refused to eat. He reportedly died of grief on Lewis’s grave. It’s a tragic ending, but it fits the legendary loyalty of the breed.

💡 You might also like: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

Cultural impact and the "Big Dog" energy

Native American tribes were often fascinated by Seaman. Some had never seen a dog that large. At one point, a group of Clatsop Indians actually stole Seaman. Lewis was furious. He sent three men after them with orders to fire if the thieves didn't give the dog back.

Think about that for a second.

Lewis was willing to risk a diplomatic incident and potential violence over his dog. That tells you everything you need to know about their bond. Seaman wasn't property; he was a member of the team.

How to trace Seaman's path today

If you’re interested in the Lewis and Clark expedition Seaman, you don’t have to just read old books. You can actually go see where this happened.

- Visit the statues: There are dozens of Lewis and Clark monuments across the U.S., from St. Louis to Seaside, Oregon. Almost all of the modern ones include Seaman. The one in St. Charles, Missouri, is particularly good.

- The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail: You can hike or drive sections of the actual route. If you bring your own dog, just remember the prickly pear lesson Lewis learned—get them some booties if you're in the plains.

- Check out the Journals: The University of Nebraska has the journals online. Use the search function for "dog" or "Seaman" to see the raw, unedited notes Lewis wrote by candlelight while the dog slept at his feet.

Actionable insights for history buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this specific piece of frontier history, skip the generic history textbooks and go straight to the source material.

- Read the "Moulton Edition": These are the definitive journals of the expedition. Look for the entries in July and August of 1805 for the most intense Seaman stories.

- Research the Newfoundland Breed: To understand why Seaman survived, you need to understand the dog. Look into their lung capacity and double-coat structure; it explains how he survived the frigid Missouri River crossings.

- Visit the Smithsonian: While the original collar mentioned by Alden was lost in a fire, the Smithsonian and various Lewis and Clark centers have replicas and detailed exhibits on the equipment Lewis bought for the dog.

The story of the expedition is often told as a tale of human grit. But without that $20 Newfoundland, the journals might have ended a lot sooner, and a lot more tragically, in the middle of a Montana grizzly encounter. Seaman earned his place in history by being the ultimate "good boy" in the most dangerous conditions imaginable.