You're looking at a number like 0.000000000000000000000000000000910938356. Honestly, it’s a nightmare. That is the mass of an electron in kilograms, by the way. If you had to write that out ten times in a lab report, you’d probably want to quit science entirely. This is exactly why scientific notation exists. It’s not just some hurdle your high school algebra teacher threw at you to be mean; it’s a survival tool for anyone dealing with the insanely big or the microscopic.

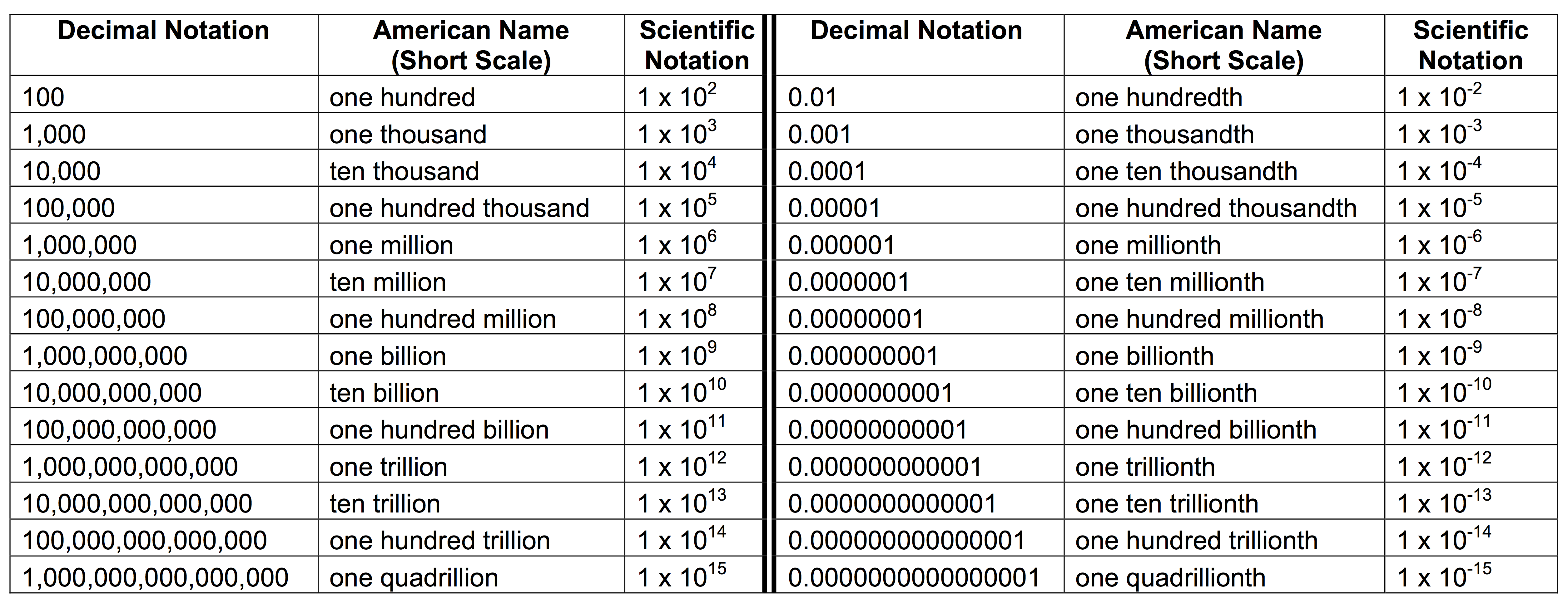

How do you scientific notation without losing your mind? It’s basically just a shorthand. Instead of writing all those zeros, we use powers of ten to tell us where the decimal point actually belongs. Think of it like a GPS for your digits.

The Anatomy of a Tiny Giant

The structure is always the same. You have a coefficient, and you have an exponent. But there's a catch that trips people up: that coefficient must be between 1 and 10. You can't have 15 x 10^3. That’s technically "engineering notation" or just bad math, depending on who you ask. It has to be 1.5.

Let’s look at the speed of light. It’s roughly 300,000,000 meters per second. In scientific notation, we write that as $3.0 \times 10^8$.

Why 8? Because if you start at the end of that 300 million and hop the decimal point to the left until you’re sitting right behind the first 3, you’ve moved eight spots. It’s a literal count of jumps. If you move left, your exponent is positive. If you’re dealing with a tiny decimal and you move right, that exponent goes negative.

How Do You Scientific Notation When Numbers Are Tiny?

Small numbers are where the real mistakes happen. People see a negative exponent and think the number itself is negative. It’s not. A negative exponent just means "divide by ten this many times."

Take a human hair. It’s about 0.00007 meters wide.

To get that into scientific notation:

- Find the decimal.

- Slide it to the right until you have a number between 1 and 10.

- In this case, you stop after the 7.

- You moved 5 places.

- Since you moved right (making a small number look "bigger"), the exponent is negative: $7.0 \times 10^{-5}$.

If you’re working in a field like microbiology or quantum computing, you’ll see this constantly. Use the "Right is Rude" (Negative) and "Left is Lift" (Positive) mnemonic if you have to. It sounds silly, but it works when you're caffeinated at 2 a.m. trying to finish a physics problem set.

Calculating Without a Meltdown

The real magic happens when you have to multiply these things. If you have $(2 \times 10^3)$ times $(3 \times 10^4)$, you don't need to expand them to 2,000 and 30,000. Just multiply the front numbers ($2 \times 3 = 6$) and add the exponents ($3 + 4 = 7$). Boom. $6 \times 10^7$.

Division is just the opposite. Subtract the exponents.

But watch out for the "re-normalization" trap. If you multiply two numbers and get 15 x 10^5, you aren't done. You have to move that decimal one more time to make it 1.5 and adjust your exponent to $10^6$. NASA engineers have actually crashed probes because of simple unit and notation errors. Well, specifically the Mars Climate Orbiter in 1999—though that was a metric-to-imperial snafu, the principle of precision remains the same. One misplaced decimal and your multimillion-dollar satellite is space dust.

🔗 Read more: iPad Cases iPad Mini: What Most People Get Wrong About Protecting the Smallest Tablet

Significant Figures: The Hidden Boss

You can't talk about how do you scientific notation without mentioning "sig figs." If your scale only measures to the nearest gram, you can't claim your object weighs 1.0000005 grams just because the math worked out that way on your calculator. Scientific notation is the best way to show how precise you’re actually being.

If you write $5 \times 10^2$, you’re saying "roughly five hundred."

If you write $5.00 \times 10^2$, you’re saying "exactly five hundred, give or take a tiny fraction."

That decimal point and the zeros following it aren't just fluff. They represent the limit of what we actually know. In the world of professional research, claiming more precision than you have is a fast way to get your paper rejected.

Real-World Use Cases

It's not just for textbooks.

- Computing: We talk about Terabytes ($10^{12}$) and Nanoseconds ($10^{-9}$).

- Finance: National debts are often so high ($10^{13}$ range) that looking at them in standard form makes the brain shut down.

- Astronomy: The distance to Proxima Centauri is $4.01 \times 10^{13}$ kilometers. Writing that out with all the zeros would take up half a page.

Practical Steps to Mastery

To actually get good at this, stop relying on your calculator’s "EE" or "EXP" button for a second and do the jumps manually.

Step 1: The "One-Digit" Rule. Always move your decimal until only one non-zero digit is to the left of it.

Step 2: The Directional Check. Look at the original number. Is it huge? Your exponent better be positive. Is it a tiny speck? It better be negative.

Step 3: The Arithmetic Shortcut. When multiplying, add exponents. When dividing, subtract them.

📖 Related: Converting Cubic Meter to Cubic Centimeter: Why Your Math Is Probably Off By a Million

Step 4: Check your "EE" button. On most TI-84 or similar scientific calculators, the "EE" button stands for "times 10 to the power of." If you type 5 EE 3, the calculator reads it as $5 \times 10^3$. Don't type 5 * 10 EE 3 or you’ll end up with $5 \times 10^4$ by mistake. That’s a classic rookie move that ruins lab grades.

The next time you’re faced with a string of zeros that looks like a bowl of Cheerios, don't blink. Just count the jumps, pick your power, and keep your coefficient between 1 and 10. It makes the universe a lot more manageable.