You’ve probably heard someone say, "You can't shout fire in a crowded theater!" It’s the ultimate "gotcha" for anyone arguing about the First Amendment. People use it to shut down debates on everything from social media censorship to political protests. But here’s the thing: that famous line comes from Schenck v. United States, and almost everyone who quotes it has no idea what the case was actually about.

Honestly, the real story is a lot messier than a simple safety warning.

Back in 1917, the U.S. was knee-deep in World War I. Tensions were high. The government wasn't exactly in a "let’s hear everyone’s opinion" kind of mood. They passed the Espionage Act, basically making it a crime to mess with military recruitment. Enter Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer. They were socialists in Philadelphia who thought the draft was basically a form of slavery. They didn't just sit around and grumble about it; they printed 15,000 leaflets telling draftees to "assert their rights" and resist the "monstrous wrong" of conscription.

They weren't calling for a violent uprising. They were mostly advocating for peaceful petitions. Still, the feds weren't having it. Schenck and Baer were arrested, convicted, and sent packing to the Supreme Court.

The Famous "Fire" Metaphor That Stuck

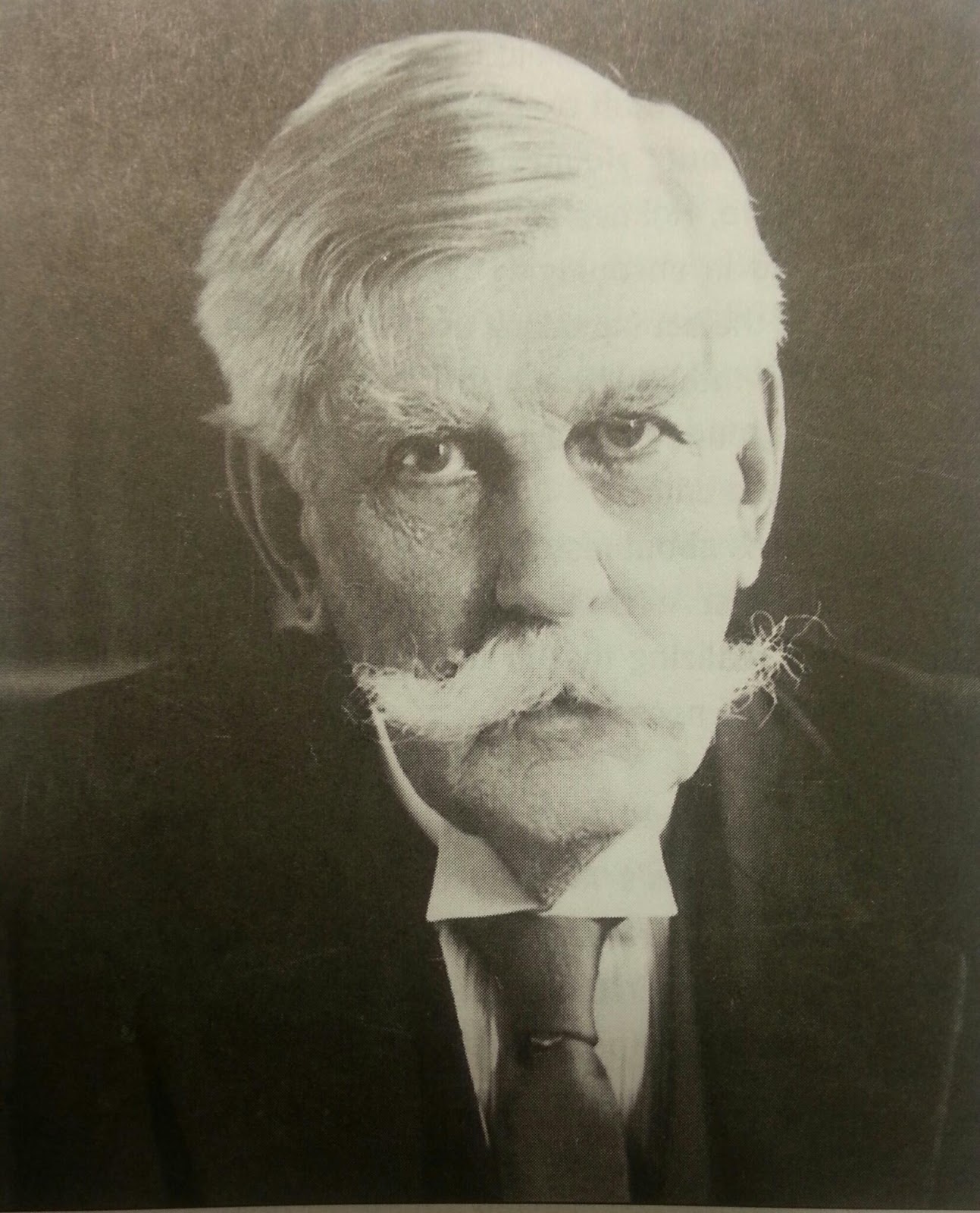

In 1919, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote the unanimous opinion for the court. He wasn't just ruling on whether Schenck was a nuisance. He was trying to figure out where the government’s power to protect the country ends and your right to speak begins.

This is where he dropped the line: "The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic."

It’s a great visual, right? You can see the stampede. But look closer. Holmes wasn't saying you can't say dangerous things. He was saying you can't say false things that cause immediate physical harm. More importantly, he used this analogy to justify putting a man in jail for distributing political pamphlets.

👉 See also: Why the University of Michigan Ends DEI as We Knew It: The Massive Shift to "Inclusive Meritocracy"

The court created the "clear and present danger" test. Essentially, if your words create a clear and present danger of bringing about "substantive evils" that Congress has a right to prevent, you're toast. In 1919, the "substantive evil" was people not showing up for the draft.

Why the Context of 1919 Changes Everything

To understand why this happened, you have to look at the vibe of the country. We were at war. The court basically argued that speech that is totally fine during peacetime becomes a threat during wartime.

"When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight."

That’s a direct quote from the ruling. It’s pretty chilling if you think about it. It suggests that the Constitution has a "pause" button that the government can hit whenever things get dicey. Schenck and Baer weren't spies. They weren't giving secrets to Germany. They were just people with an unpopular opinion about a war they hated.

The Problem With "Clear and Present Danger"

The biggest issue with the test Holmes invented was that it was incredibly vague. What counts as "clear"? What counts as "present"?

For years after Schenck v. United States, the government used this standard to crack down on all sorts of dissent. If you were a socialist, a communist, or just someone who thought the government was making a mistake, the "clear and present danger" test was a convenient way to lock you up. It turned the First Amendment into a "sometimes" right rather than an "always" right.

The Plot Twist: Holmes Changed His Mind

Here’s a detail most history books skip over. Only a few months after Schenck, another case called Abrams v. United States came along. The facts were similar—more leaflets, more anti-war sentiment. But this time, Holmes flipped.

🔗 Read more: What Prevents You From Being Drafted: The Real Rules of Selective Service

He realized the "clear and present danger" test was being used as a weapon to crush any opinion the government didn't like. He wrote a famous dissent in Abrams, arguing for a "marketplace of ideas." He started to realize that the best way to fight bad ideas isn't with a jail cell, but with better ideas.

It took decades for the rest of the Court to catch up to him.

Is Schenck Still the Law Today?

Kinda, but mostly no.

The "clear and present danger" test is basically dead. In 1969, a case called Brandenburg v. Ohio effectively replaced it. The Supreme Court decided that the government can only punish speech if it is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action."

| Feature | Schenck (1919) | Brandenburg (1969) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | Clear and Present Danger | Imminent Lawless Action |

| Focus | Could it eventually cause harm? | Is it about to cause a crime right now? |

| Protection | Very weak for dissenters | Very strong for almost all speech |

Basically, today you can say the draft is slavery. You can say the government is corrupt. You can even say we should have a revolution. As long as you aren't standing in front of a mob pointing at a building and saying "Go burn that down right now," you're usually protected.

What This Means for You in 2026

We live in a world where everyone is shouting "fire" in the digital theater every single day. People still use the Schenck logic to argue that "misinformation" or "hate speech" should be illegal because they are "dangerous."

But when you hear someone quote the "shouting fire" line, you should remember that it was originally used to jail a guy for printing flyers. It was a tool of censorship, not a tool of safety.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Citizen

- Verify the "Fire" Quote: If someone uses the theater analogy to argue for restricting speech, remind them that the analogy was about falsely shouting fire. Context matters.

- Understand the Brandenburg Standard: If you’re worried about whether something you say is legal, ask: "Am I inciting immediate violence?" If the answer is no, the First Amendment is likely on your side.

- Watch the Legislation: Laws like the Espionage Act are still on the books. They’ve been used recently against whistleblowers and journalists. The spirit of Schenck lives on in how the government handles "national security" leaks.

- Read the Original Dissent: Look up Holmes’ dissent in Abrams v. United States. It’s much more relevant to our modern idea of free speech than his majority opinion in Schenck.

Schenck v. United States is a reminder that civil liberties are fragile, especially when people are scared. The "clear and present danger" test was a mistake born of wartime panic. We’ve moved past it legally, but we haven't quite moved past the urge to silence people who make us uncomfortable. Knowing the history helps you make sure we don't head back there.

🔗 Read more: Latest News in Venezuela Today: Why Everything Just Changed

To get a better grip on how these laws affect you today, check out the current status of the Espionage Act and how it’s being applied to modern whistleblowers. Understanding the evolution of these "danger" tests is the only way to protect your own right to speak up.