Ever seen a mechanical arm move so fast it’s basically a blur? If you’ve watched a video of a circuit board being built or a box of chocolates being packed at lightning speed, you’ve probably seen a SCARA robot in its natural habitat. It stands for Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm. Honestly, the name is a bit of a mouthful, but the "selective compliance" part is the secret sauce. It means the arm is rigid in one direction but has a little "give" or flexibility in another.

Think about it like this. If you try to push a peg into a hole and you’re off by a fraction of a millimeter, a completely rigid machine might just snap the part. A SCARA robot is designed to be stiff vertically—so it can press down hard—but slightly flexible horizontally. This allows it to "settle" into place. It’s the difference between a stiff wooden board and a high-end fishing rod. One snaps; the other adapts.

The Inner Workings of the SCARA Design

Most people see a robotic arm and think of the giant ones used to weld car frames. Those are usually six-axis robots. They move like a human arm, twisting and turning in every possible direction. A SCARA robot is much simpler, and that simplicity is why it’s so incredibly good at what it does.

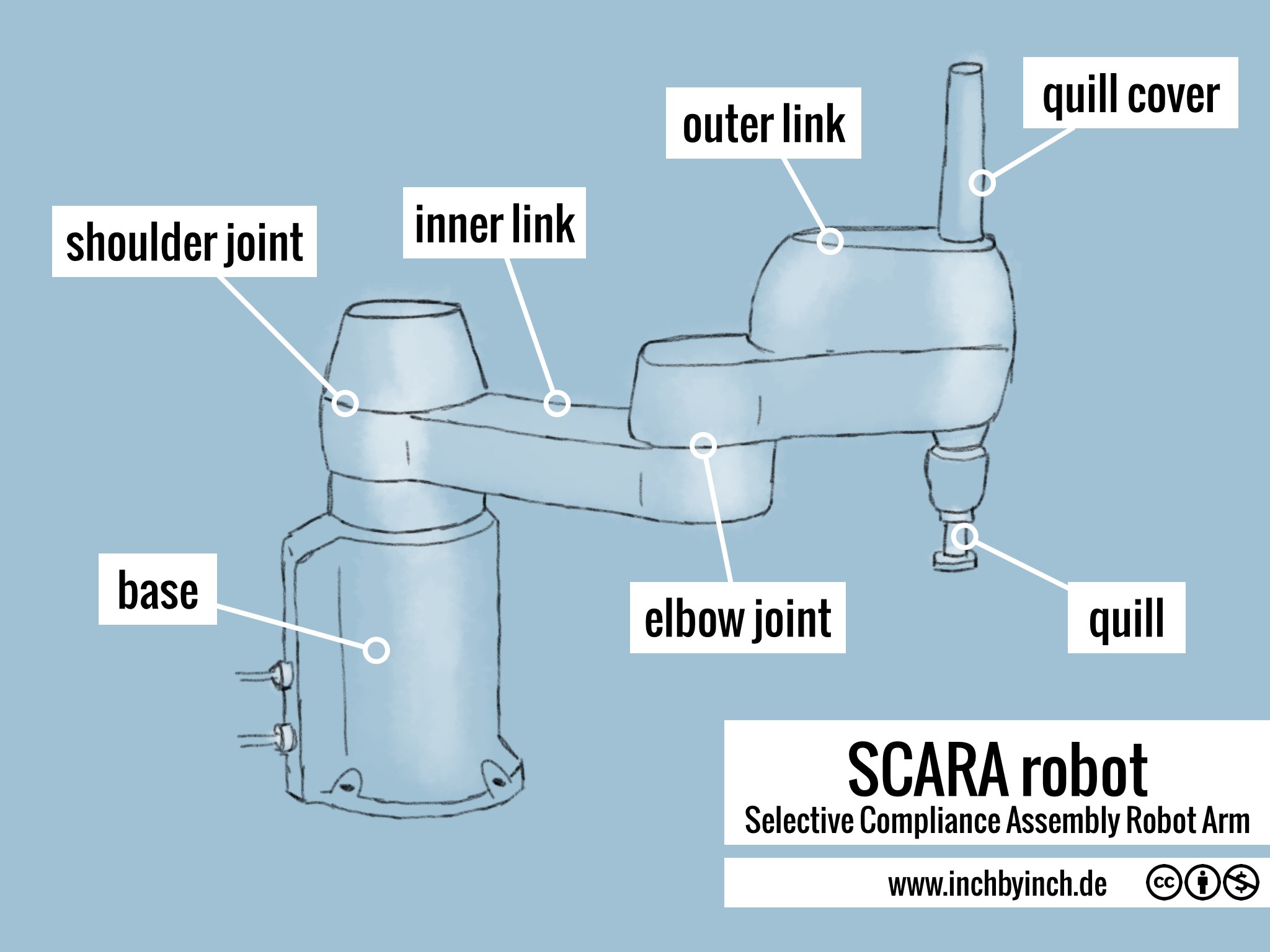

It’s essentially a 4-axis machine. Imagine two linkages connected by a joint, sitting on a pedestal. It moves in a way that’s very similar to how your arm moves if you laid it flat on a table and swung your elbow and wrist back and forth. This creates a cylindrical work envelope. It can reach out, pull back, and rotate. The fourth axis is the "Z" motion—the up and down movement at the end of the arm, usually called the quill or the stroke.

Why the 4-axis limitation is actually a superpower

You might think four axes are worse than six. Wrong. Because the SCARA has fewer joints to manage, it is inherently faster. It’s also much more repeatable. When we talk about "repeatability" in robotics, we’re talking about the machine’s ability to return to the exact same spot over and over again. High-end models from brands like Epson or Denso can hit the same spot within 0.01 millimeters. That’s thinner than a human hair.

If you tried to make a six-axis robot move that fast for a simple "pick and place" task, the vibration would be a nightmare. The SCARA's design keeps it stable. It’s built for the "flat" world. Since most electronics and small mechanical assemblies are built in layers, you don't need a robot that can upside-down-backflip. You just need one that can grab a chip from a tray and slam it onto a PCB with surgical precision.

Where You’ll Actually Find These Things Working

Let's look at some real-world applications. If you’re holding a smartphone right now, a SCARA robot almost certainly helped build it.

- Electronics Assembly: This is the big one. Screwing in tiny fasteners, applying thermal paste, or placing micro-connectors. Companies like Foxconn use thousands of these.

- The Medical Field: Not for surgery, usually, but for lab automation. Moving test tubes or sorting samples in high-volume testing labs.

- Food and Beverage: Think about those perfectly aligned trays of cookies or syringes. A SCARA can pick up a delicate item with a vacuum gripper and place it in a blister pack faster than your eye can track.

- Automotive Sub-assembly: While the big 6-axis robots weld the chassis, SCARAs are in a smaller cell nearby, assembling the fuel injectors or the infotainment screen.

A cool example comes from the world of watchmaking. Brands that aren't strictly "hand-made" use SCARA arms to handle tiny gears that are too small for even the steadiest human hand to manage 24/7 without a mistake. Fatigue doesn't exist for these machines.

Comparing SCARA to Delta and Cartesian Robots

It's easy to get confused between the different types of industrial robots. You’ve probably seen the "spider" robots—those are Delta robots. They hang from the ceiling and use three thin arms to move a platform. Deltas are faster for very light things, but they have almost no "payload" capacity. If you need to move something that weighs 5kg or 10kg, a Delta is going to struggle.

Then you have Cartesian robots. These move on tracks—left/right, forward/backward, up/down. They are great for massive areas, like a giant 3D printer or a CNC machine. But they are slow. They take up a lot of floor space.

The SCARA robot is the middle ground. It has a small footprint—usually just a single base pedestal—but a large reach. It’s faster than a Cartesian and stronger than a Delta. It’s the "Goldilocks" of the automation world.

The Cost Factor: Is it Worth the Investment?

A decade ago, putting a robot in your shop was a million-dollar endeavor. Not anymore. You can find "entry-level" SCARA units for $10,000 to $15,000. Of course, the high-speed, high-precision industrial versions from Fanuc, ABB, or KUKA will still cost you a pretty penny, especially when you factor in the "end effector" (the hand) and the safety guarding.

But here’s the kicker: the ROI (Return on Investment) is usually under 12 months in high-volume settings. If a human can do 10 assemblies a minute and a SCARA can do 60, the math solves itself. Plus, the robot doesn't need lunch breaks or health insurance. That sounds cold, but in the world of global manufacturing, it's just reality.

Misconceptions and Limitations

Don't go thinking a SCARA can do everything. They have weaknesses.

First, they are "work-envelope" limited. Because of the way the arms fold, they actually have a "dead zone" right near their own base. It's like trying to scratch the middle of your own back—the geometry just doesn't work.

Second, they are strictly for horizontal planes. If you need to pick a part up and flip it over to work on the bottom, a standard SCARA can't do that. You’d need to add a "fifth axis" or a separate turnover station.

Lastly, there's the payload. While they are stronger than Deltas, they aren't meant for heavy lifting. Most top out at around 10kg to 20kg. If you’re trying to move engine blocks, you’re looking at the wrong machine.

The Software Side

The "brain" of the robot has come a long way. In the 90s, you had to code every single coordinate by hand. It was miserable. Today, most SCARA robot systems use "lead-through" programming or intuitive GUIs. You can literally move the arm to the points you want, click "save," and the software calculates the most efficient path.

Vision systems have also changed the game. In the past, parts had to be perfectly lined up in a tray for the robot to find them. Now, we use "Visual Servoing." A camera looks at a pile of messy parts on a conveyor belt, tells the robot exactly where they are and what angle they’re at, and the robot adjusts on the fly. It's kinf of incredible to watch.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Google Profile Picture Size Actually Matters (And How to Fix It)

What to Look for When Choosing One

If you're looking into automation, don't just buy the fastest one. Speed creates heat and wear.

- Reach: Measure your workspace. Do you need the arm to reach 400mm or 1000mm? Larger arms take up more space and are slightly less precise.

- Cycle Time: This is the "God metric" in manufacturing. How many seconds does it take to go from point A to point B and back?

- Environment: Are you working in a cleanroom? You'll need a specific "Cleanroom Class" rated SCARA that doesn't shed particles or grease. Working with food? You need "washdown" capability so you can spray it with disinfectant without frying the electronics.

- Inertia: This is a technical one. It's not just the weight of the part, but the weight of the gripper plus the part, and how far out that weight is being held. If you ignore inertia, you'll burn out the motors in months.

Practical Steps for Implementation

Don't just buy a robot and bolt it to the floor. Start with a "feasibility study." Most distributors will let you send them your parts, and they’ll run a simulation to prove the robot can actually hit your cycle time targets.

Next, think about safety. SCARA robots move fast—fast enough to be lethal if they hit a person. You’ll need light curtains, physical cages, or specialized sensors that slow the robot down when a human gets close.

Finally, consider the "end of arm tooling" (EOAT). The robot is just a dumb arm; the gripper is the business end. Whether it’s a mechanical jaw, a vacuum cup, or a magnetic picker, the EOAT is often more complex to design than the robot itself.

If you're serious about integrating a SCARA robot, start by mapping your most repetitive, boring, and high-speed task. That's where the machine will shine. Look at your current scrap rate. If humans are dropping 5% of the parts because they’re tiny and annoying to handle, the robot will pay for itself in saved material alone.

Get a quote that includes the controller and the cables. You'd be surprised how many people forget that the "brain" box is often a separate, large cabinet that needs its own home. Plan your floor space accordingly. Check your power requirements; most of these need 220V or 3-phase power to hit those top speeds.

Once it's running, keep the joints greased. A well-maintained SCARA can run for 10 years or more without a major overhaul. It's one of the few pieces of tech that doesn't become obsolete the moment a new model comes out. If it can move from A to B reliably, it's still making you money.