It is arguably the most famous magazine cover in history. Even if you don’t know the name of the artist or the specific date it hit newsstands, you have seen it. You’ve seen the parodies. You’ve seen the posters in college dorms or hanging in the hallways of pretentious Upper West Side apartments.

The View of the World from 9th Avenue, drawn by Saul Steinberg for the March 29, 1976, issue of The New Yorker, is a masterclass in psychological geography. It isn't a map of a city. It's a map of an ego.

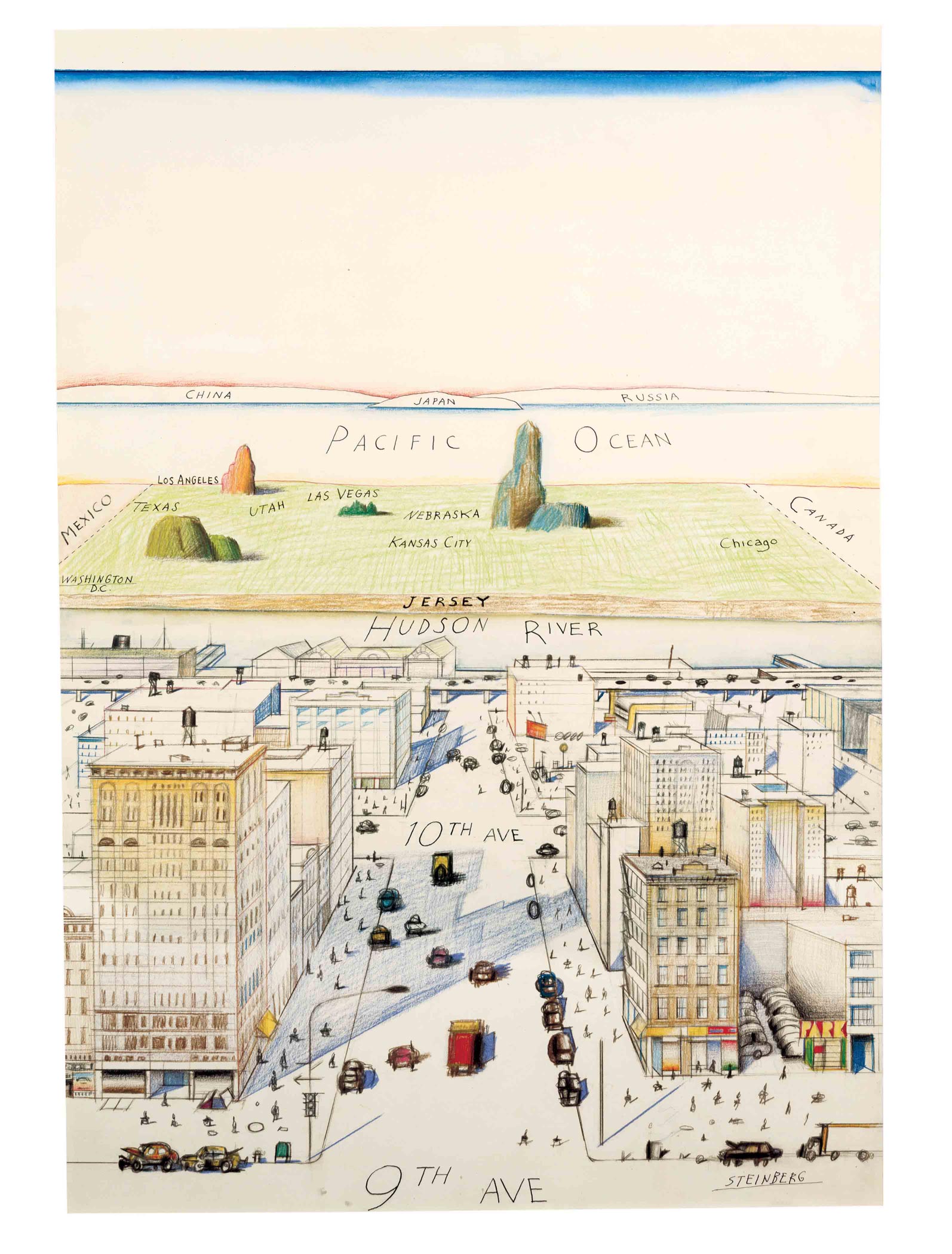

Looking at it, you see the detailed, cluttered blocks of Ninth and Tenth Avenues in the foreground. Then, the Hudson River. Beyond that? A brown strip of land labeled "Jersey." The rest of the United States is a series of flat, nondescript rectangles—Kansas, Nebraska, Utah—leading to the Pacific Ocean and a few tiny bumps representing China and Japan. It captures a very specific, very hilarious, and very arrogant mental state.

What Steinberg Was Actually Doing

Steinberg wasn't just making fun of New Yorkers. Well, he was, but there was more to it. He was a Romanian immigrant, a man who viewed the world through the lens of symbols and social shorthand. To him, the View of the World from 9th Avenue was an exploration of how we all process space.

We all do this. Your "world" is basically your neighborhood, your commute, and your favorite coffee shop. Everything else is a blur. For the 1970s New Yorker, the "rest of the world" was just a vague obstacle between them and the rest of the planet.

The drawing is deceptively simple. If you look closely at the original, you'll notice the precision of the architecture on the Manhattan streets. The brownstones have character. The cars are specific. Then, as your eye travels west, the world loses its "resolution." It’s like a video game that hasn't fully rendered the distant mountains.

The Legal War Over a Sketch

You might think a drawing like this would just exist peacefully in the archives. Nope. It actually became the center of a landmark copyright case: Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. (1987).

When the movie Moscow on the Hudson came out, the promotional poster looked suspiciously like Steinberg’s work. It had that same flattened perspective, the same focus on a New York street with a vague world beyond. Steinberg sued. The court eventually ruled in his favor, deciding that the movie poster had indeed swiped the "expressive" elements of his style.

👉 See also: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

This case is still taught in law schools today. It defines the line between "taking an idea" and "taking an expression." You can draw a map from a window, but you can't draw Saul Steinberg's map from a window.

Why It Still Hits Today

Honestly, the View of the World from 9th Avenue is more relevant now than in 1976. Why? Because of the internet.

We live in digital bubbles that function exactly like Steinberg’s 9th Avenue. Our Twitter feeds or TikTok algorithms are the foreground. They are detailed, vibrant, and consume 90% of our attention. The "real world" outside our digital preferences is just a flat, uninteresting Kansas.

The drawing resonates because it’s a portrait of parochialism. It’s about the narrowness of the human experience. Whether you’re a New Yorker in 1976 looking at Jersey or a tech bro in 2026 looking at "flyover country," the mental map is identical.

The Anatomy of the Image

Let’s break down what you’re actually looking at when you see the poster.

- The Foreground: 9th Avenue and 10th Avenue. They are the center of the universe. The buildings are colorful and have depth. There are people. There is life.

- The Hudson River: A thin, blue line. It’s the border of civilization.

- The Rest of America: It’s basically a wasteland. Washington D.C. is a tiny speck. Texas is a blob.

- The Horizon: The Pacific Ocean is smaller than the Hudson. The rest of the world—Russia, China, Japan—are just afterthoughts on the edge of the paper.

It’s a visual joke that lands instantly. You don't need a degree in art history to get it. You just need to have felt, at some point, that where you are is the only place that matters.

Misconceptions About the Artist

People often think Steinberg was a typical, arrogant New Yorker. He wasn't. He was a refugee who fled Italy during World War II. He arrived in the U.S. with a deep skepticism of authority and a keen eye for how people use style to mask their insecurities.

✨ Don't miss: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

He didn't consider himself a cartoonist. He called himself "a writer who draws."

When he created the View of the World from 9th Avenue, he didn't realize it would become his legacy. In fact, he later grew to resent it. It overshadowed his more complex, abstract work. He once complained that he was "the man who did that poster," as if his decades of other contributions to The New Yorker didn't exist.

How to See it Like an Expert

If you want to truly appreciate the work, stop looking at it as a poster. Look at it as a piece of journalism.

In 1976, New York was a mess. It was literally on the verge of bankruptcy. The "view" from 9th Avenue wasn't actually that pretty in real life. It was gritty, dangerous, and dirty. By drawing it with such whimsical detail, Steinberg was making a statement about the resilience of the city's inhabitants. They loved their crumbling blocks so much they barely noticed the rest of the continent existed.

Nuance matters here. Steinberg wasn't saying New York was better than Nebraska. He was saying New Yorkers thought it was, and that there is something both pathetic and charming about that delusion.

Practical Ways to Apply the "Steinberg Lens"

Understanding this perspective can actually change how you interact with the world. It’s about recognizing your own "9th Avenue."

First, map your own biases. If you were to draw your daily life, what would be in the foreground? What are the "Kansas" parts of your life—the things you ignore or oversimplify because they aren't right in front of you?

🔗 Read more: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Second, look at how brands use this. Travel companies often use a "Steinberg" perspective to make a destination feel like the center of the world. They blow up the tiny details of a resort and shrink the travel time or the surrounding poverty into a thin strip on the horizon.

Third, acknowledge the limits of your "view." The View of the World from 9th Avenue is a reminder that our perspective is always skewed. We are all, in some way, standing on 9th Avenue looking out at a world we don't fully understand.

Taking Action: Beyond the Poster

Don't just buy the print and stick it on your wall. Use it as a prompt for a bit of self-awareness.

Go to a window in your house or office. Look out. Try to draw—or even just list—what you see, but scale the items based on how much you care about them. The coffee shop you visit every morning should be huge. The office building where you work but hate? Make it a tiny, gray square. The house of your ex? Maybe it doesn't even make the map.

This exercise isn't about art; it's about identifying your personal "Hudson River." Once you know where your borders are, you can start to cross them.

The real power of Saul Steinberg’s masterpiece isn't in the humor. It’s in the realization that there is a whole, vibrant, complex world out there beyond the Pacific—and maybe it's time we stopped drawing it so small.

To dive deeper into this specific era of art, you should look into the archives of The New Yorker from the mid-70s. The magazine was a different beast then, full of long-form, meandering essays that mirrored Steinberg’s own intellectual curiosity. You can also visit the Saul Steinberg Foundation website, which maintains an incredible digital catalog of his more "serious" work, proving he was much more than just the guy who drew a funny map.

Look at his "Diplomas" or his "Passports." They explore the same themes of identity and geography but with a darker, more philosophical edge. Once you see the rest of his portfolio, the View of the World from 9th Avenue feels less like a standalone gag and more like one chapter in a lifelong study of the human ego.