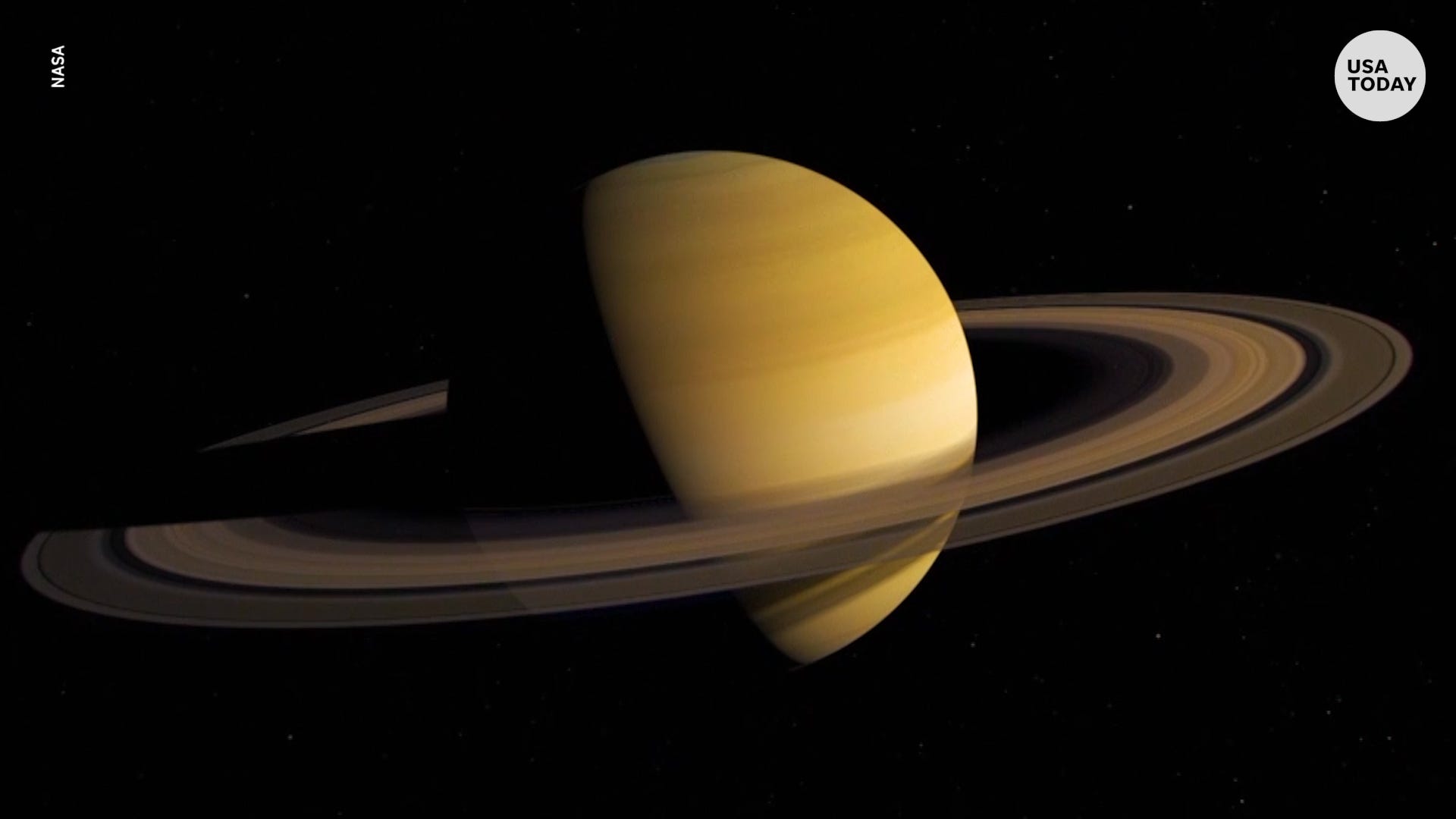

If you could shrink yourself down and float through the crown of our solar system, you wouldn't find a solid road of gold or a shimmering sheet of glass. Most people imagine Saturn's rings as these massive, flat disks—kinda like a cosmic vinyl record. But the reality is much messier. And colder. When we talk about what Saturn's rings are made of, we are basically talking about a massive, swirling demolition derby of ice.

It's nearly all water ice. Think 99.9%.

But it isn't just "ice" like the cubes in your freezer. This stuff ranges from microscopic specks that look like cigarette smoke to jagged boulders the size of a suburban house. Occasionally, you’ll even find "moonlets" as big as mountains embedded right in the flow. It's a chaotic, glittering debris field that stretches out for 175,000 miles, yet it's incredibly thin—sometimes only 30 feet deep in certain spots. That's thinner than a two-story building. If you built a scale model of the rings out of a sheet of paper, the paper would actually be too thick.

Why Water Ice is the Secret Sauce

Honestly, the purity of the ice is what trips scientists up. When NASA’s Cassini spacecraft spent 13 years looping around the gas giant, it sent back data that made researchers like Linda Spilker scratch their heads. If the rings were billions of years old, they should be "dirty." Space is full of "micro-meteoroid" soot—basically dark dust that should have coated the rings and turned them charcoal gray by now. Instead, they’re bright. They’re dazzling. This suggests that what Saturn's rings are made of might be a relatively new addition to our neighborhood. We’re talking maybe only 10 to 100 million years old. When dinosaurs were walking the Earth, Saturn might have been "naked."

The ice stays bright because it’s constantly being ground down and refreshed. Gravity from Saturn’s dozens of moons tugs on these particles. They collide. They shatter. They clump back together. It’s a self-cleaning oven made of frozen water. There's a tiny bit of rocky material mixed in—silicates and organic compounds—which gives the rings those subtle pinks, grays, and browns you see in high-resolution photos. But that’s just the seasoning. The main course is pure $H_2O$.

The Death of a Moon: Where it all came from

Where do you get that much ice? You don't just find it floating in a neat circle by accident.

👉 See also: Doom on the MacBook Touch Bar: Why We Keep Porting 90s Games to Tiny OLED Strips

One leading theory involves a "lost moon" named Chrysalis. About 160 million years ago, this moon might have gotten too close to Saturn—crossing what we call the Roche Limit. This is the "no-go zone" where a planet's gravity is so strong it literally rips a moon apart. Saturn’s tidal forces would have tugged harder on the front of Chrysalis than the back, stretching it like taffy until it popped. The rocky core likely dove into the planet, but the icy outer layers stayed in orbit, shattering into the billions of pieces we see today.

Another possibility? A massive comet or a Kuiper Belt object wandered too close and got pulverized. Either way, the rings are a graveyard. A beautiful, shimmering graveyard of a world that didn't survive the neighborhood bully's gravity.

The Ring Structure is a Messy Neighborhood

It’s easy to look at the A, B, and C rings and think they’re all the same. They aren’t.

The B Ring is the heavyweight. It’s the brightest and most opaque because it’s packed dense with ice. If you tried to fly a ship through it, you'd be playing a lethal game of dodgeball. Then you have the Cassini Division, a 3,000-mile wide gap that looks empty but is actually just less crowded.

Then there's the F Ring. This one is weird. It’s held together by "shepherd moons" like Prometheus and Pandora. These tiny moons act like sheepdogs, using their gravity to whistle the stray ice particles back into line. Without them, the F ring would just bleed out into space. It's a delicate balancing act of physics.

✨ Don't miss: I Forgot My iPhone Passcode: How to Unlock iPhone Screen Lock Without Losing Your Mind

Is the Ice Disappearing?

We’re actually catching Saturn at a very specific time in history. The rings are dying.

Cassini observed something called "ring rain." Basically, Saturn’s magnetic field is "cooking" the rings with UV light, turning the ice into charged ions. These ions then get pulled down the magnetic field lines into Saturn's atmosphere. It’s essentially a torrential downpour of water falling from the rings into the planet.

- Saturn loses about a swimming pool’s worth of water every half hour.

- At this rate, the rings will be gone in about 100 million years.

- The "C Ring" is thinning out faster than the rest.

James O'Donoghue, a planetary scientist who worked with NASA data, has pointed out that we are incredibly lucky to be alive during the brief window when Saturn has its jewelry. Give it a few million years, and it might just be another bland gas giant.

The Mystery of the "Spokes"

Every now and then, astronomers see these dark, ghostly streaks across the rings. They look like spokes on a bicycle wheel. We used to think it was a camera glitch, but it’s real. These spokes are likely tiny, dust-sized grains of ice that get levitated by static electricity. When Saturn’s magnetic field interacts with the sun’s radiation, it creates a charge that lifts these particles out of the main ring plane. They hover there for a few hours and then vanish. It's like a cosmic magic trick that we still haven't fully mapped out.

It's also worth noting that what Saturn's rings are made of varies by location. In the innermost rings, the ice is hammered by radiation, changing its crystalline structure. In the outer E ring, the material is actually being "replenished" by a moon. Enceladus, a tiny moon with a subsurface ocean, shoots giant geysers of water ice out of its south pole. That "spray" creates the E ring. So, in one part of the system, we’re seeing the debris of a dead moon, and in another, we’re seeing the "breath" of a living one.

🔗 Read more: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

Misconceptions People Still Believe

- They are solid. Nope. You could fly a drone through most of it if you were careful.

- They are thick. As mentioned, they are insanely thin relative to their width.

- They are permanent. They are a fleeting moment in the solar system's life.

- They are unique. Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune all have rings. Saturn's are just the only ones made of bright, reflective ice. The others are made of dark dust and rock, which is why they’re so hard to see.

How to See Them Yourself

You don't need a billion-dollar telescope. Even a basic 4-inch backyard telescope will show you the rings. You won't see individual ice boulders, obviously, but you'll see that distinct "ear" shape that Galileo first saw in 1610 (he actually thought they were giant moons or "handles").

If you want to track the movement of what Saturn's rings are made of, watch for "Opposition." This is when Earth is directly between the Sun and Saturn. The rings get significantly brighter because the ice particles reflect the sunlight directly back at us. It’s called the Seeliger Effect.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly appreciate the scale and composition of Saturn's rings, start by downloading a sky-tracking app like Stellarium or SkyGuide to locate Saturn in your current night sky. It’s often visible as a steady, yellowish "star." If you’re looking to go deeper, check the NASA Solar System Exploration website for the latest "Grand Finale" raw images from the Cassini mission; these photos show the texture of the ring ice in terrifyingly beautiful detail. For those who want the math, look up the "Roche Limit formula" to understand exactly how close a moon has to get before it turns into a ring. Finally, keep an eye on the upcoming Dragonfly mission news; while it's heading to Titan, the data it sends back about the Saturnian environment will inevitably tell us more about the fate of those iconic icy bands.