You’ve probably heard for decades that whole milk is basically a heart attack in a glass. The logic was simple. Saturated fat in milk raises your LDL cholesterol, and high LDL cholesterol clogs your arteries. End of story. But honestly, nutrition science is rarely that neat, and the "war on fat" is starting to look like a massive oversimplification that ignored how food actually works in your body.

When you pour a glass of cold milk, you aren't just drinking a bucket of lipids. You're consuming a complex biological matrix. This "food matrix" effect is the secret reason why the saturated fat in milk doesn't behave the same way as the fat in a greasy pepperoni pizza or a cheap store-bought pastry. Research is increasingly showing that the structures surrounding the fats in dairy might actually protect your heart rather than harm it. It’s wild to think about, but your 2% or whole milk habit might not be the dietary villain it was made out to be in the 1990s.

The Cholesterol Confusion

Let's get into the weeds for a second. We’ve been told to fear saturated fat because it bumps up LDL—the "bad" cholesterol. And it does. But here’s the kicker: not all LDL is created equal. There are large, fluffy LDL particles and small, dense ones. It’s the small, dense ones that tend to get stuck in your artery walls and cause problems. Recent studies, including those published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, suggest that the saturated fat in milk tends to increase the large, buoyant LDL particles, which are significantly less dangerous.

It’s also about the ratio. If you’re drinking whole milk and your HDL (the "good" stuff) goes up alongside your LDL, your overall cardiovascular risk profile might not change much at all. Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a cardiologist and dean at the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, has spent years pointing out that dairy fat consumption isn't linked to heart disease in the way we once assumed. In fact, some of his research found that people with higher levels of dairy-fat biomarkers in their blood actually had a lower risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

Why the Milk Fat Globule Membrane (MFGM) Matters

If you want to understand why a chunk of butter affects you differently than a glass of milk, you have to look at the MFGM. This is a thin, three-layered coating that surrounds every tiny droplet of fat in milk. It's packed with proteins, phospholipids, and sphingolipids.

When you drink milk, this membrane acts like a buffer. It seems to interfere with how your body absorbs the fat and how your liver processes it. However, when you churn milk to make butter, you break that membrane. That’s why butter—which is basically naked milk fat—tends to spike blood cholesterol much more aggressively than milk or cheese. It’s the same fat, just without its "packaging."

Cheese is another fascinator. Even though it's high in saturated fat, many clinical trials show it has a neutral or even beneficial effect on heart health. Why? Fermentation. The bacteria used to make cheese create short-chain fatty acids and other compounds that change how your metabolism reacts.

Does it actually make you gain weight?

This is where things get really counterintuitive. You’d think that switching from whole milk to skim would be a slam dunk for weight loss. Fewer calories, right? Well, the data says otherwise.

Observational studies have repeatedly shown that children and adults who consume full-fat dairy tend to be leaner than those who go for the fat-free versions. There are a few theories for this. First, fat is satiating. It triggers the release of hormones like cholecystokinin (CCK) that tell your brain you're full. If you drink a watery glass of skim milk, you might find yourself reaching for a cookie twenty minutes later because you aren't satisfied.

Second, there is a specific type of fat in dairy called Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA). Some evidence suggests CLA can help with fat burning and muscle retention, though the effects in humans are likely pretty small. Still, it’s a far cry from the "milk makes you fat" mantra.

The Dairy Industry and Scientific Bias

We have to be honest here: the dairy industry spends a lot of money on research. Whenever you see a study saying "Milk is a Superfood," it’s worth checking the funding. But even independent, large-scale meta-analyses—the kind that pool data from hundreds of thousands of people—are struggling to find a solid link between saturated fat in milk and early death.

For example, the PURE study (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology), which followed over 130,000 people across 21 countries, found that dairy consumption was associated with a lower risk of mortality and major cardiovascular events. That doesn't mean you should start chugging a gallon a day. It just means the blanket advice to avoid dairy fat "at all costs" is likely outdated for the general population.

What about the "Pro-Inflammatory" Argument?

You’ll hear influencers on social media claim that dairy is "highly inflammatory." This is a massive generalization. For people with a genuine cow's milk protein allergy or severe lactose intolerance, yes, dairy causes inflammation because their immune system or gut is reacting to it.

But for most people? The science doesn't back it up. A systematic review of 52 clinical trials published in Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition found that dairy actually has anti-inflammatory properties for the majority of the population, especially those with metabolic issues.

Identifying the Real Culprit

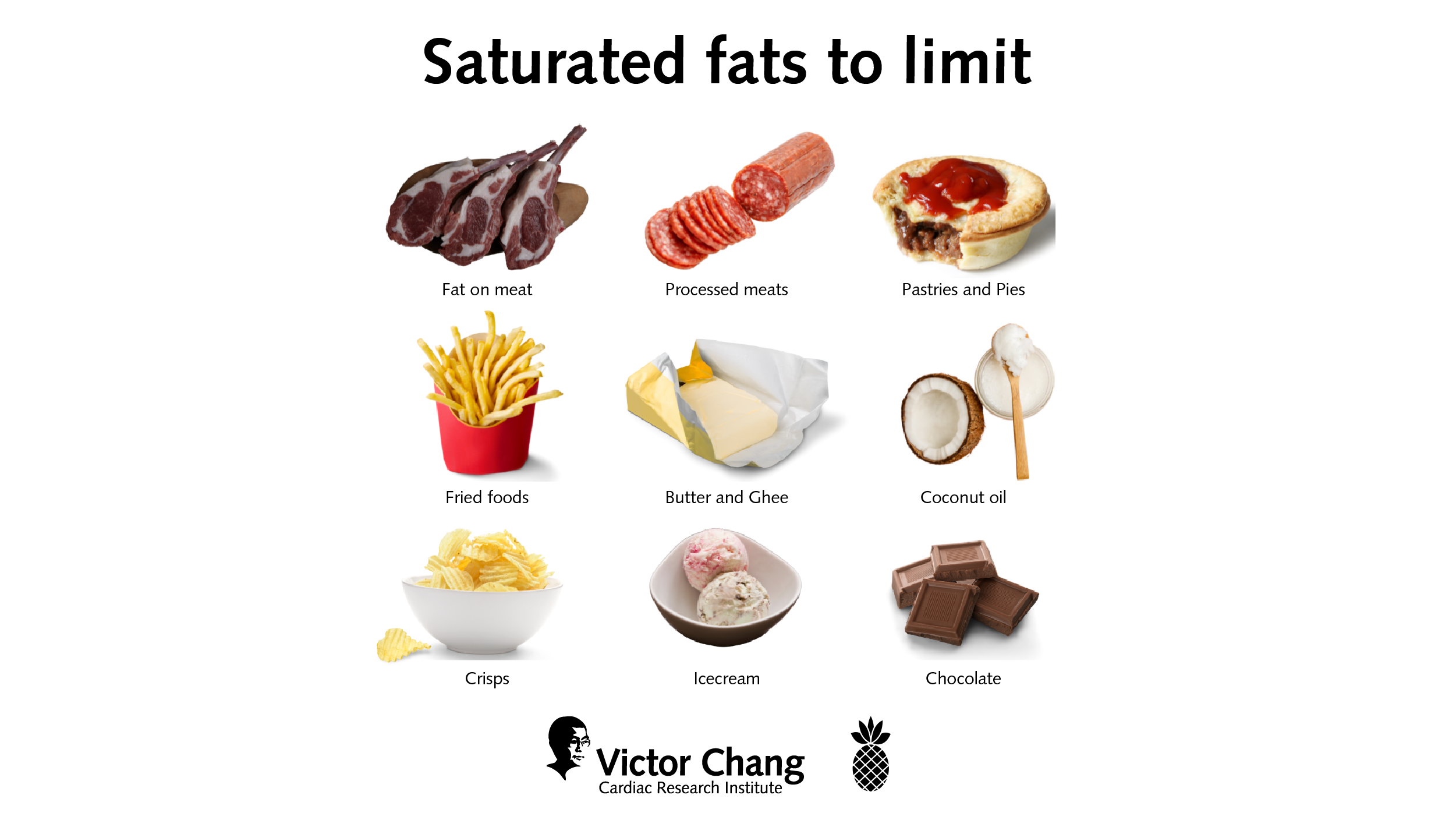

The real danger isn't the saturated fat in milk itself; it’s what we eat with it. A glass of whole milk with a steak and a loaded baked potato is a lot of saturated fat in one sitting. But a splash of whole milk in your coffee or a bowl of full-fat Greek yogurt with berries? That’s a completely different metabolic story.

Context is everything. If your diet is already high in ultra-processed foods and refined sugars, adding more saturated fat is like throwing gas on a fire. But in the context of a Mediterranean-style diet or a whole-foods-based approach, dairy fat seems to be a neutral player or even a slight net positive.

✨ Don't miss: Why High Blood Pressure and Heat Intolerance Make Summer So Dangerous

Practical Steps for Your Grocery Run

So, how do you actually apply this at the supermarket? Don't just look at the fat percentage.

- Check the ingredients. If you're buying "low fat" or "fat-free" yogurt, check for added sugar. Manufacturers often pump these products with sugar or corn starch to make up for the lost texture and flavor of the fat. You're trading a natural fat for a refined carb—a bad deal for your insulin levels.

- Consider the source. Grass-fed milk generally has a better fatty acid profile than grain-fed milk, including higher levels of Omega-3s and CLA. It’s pricier, but if you’re worried about the quality of the fat you’re eating, it’s a legitimate upgrade.

- Listen to your gut. If you feel bloated or sluggish after drinking whole milk, it doesn't matter what the "heart health" studies say. Your individual bio-individuality trumps the population average.

- Don't fear the cream. If you prefer the taste of 2% or whole milk, the current evidence suggests you don't need to force yourself to drink skim for the sake of your arteries. Just keep an eye on your total caloric intake.

The conversation around the saturated fat in milk is a perfect example of why nutrition is a moving target. We used to think of nutrients in isolation—fat is bad, sugar is bad, protein is good. Now, we realize it's the whole food that matters. The proteins, minerals, and unique membranes in milk change how the fat behaves.

Moving forward, focus on the quality of your dairy. Fermented options like kefir and yogurt are usually the "gold standard" because you get the benefits of the fat matrix along with probiotics. If you're sticking to liquid milk, choose the one that makes you feel the most satiated and satisfied. The era of fearing the milkmaid is over; it's time to look at the bigger picture of your metabolic health.

Actionable Takeaways

- Switch to fermented dairy like kefir or aged cheeses to get the cardiovascular benefits of the dairy matrix and fermentation byproducts.

- Stop prioritizing "fat-free" labels if it means you're consuming more added sugars or feeling less full after meals.

- Get a full lipid panel that looks at your ApoB levels or LDL particle size if you have a family history of heart disease, rather than just guessing based on your milk intake.

- Prioritize grass-fed or organic dairy when possible to ensure a higher concentration of beneficial fatty acids like Omega-3 and CLA.