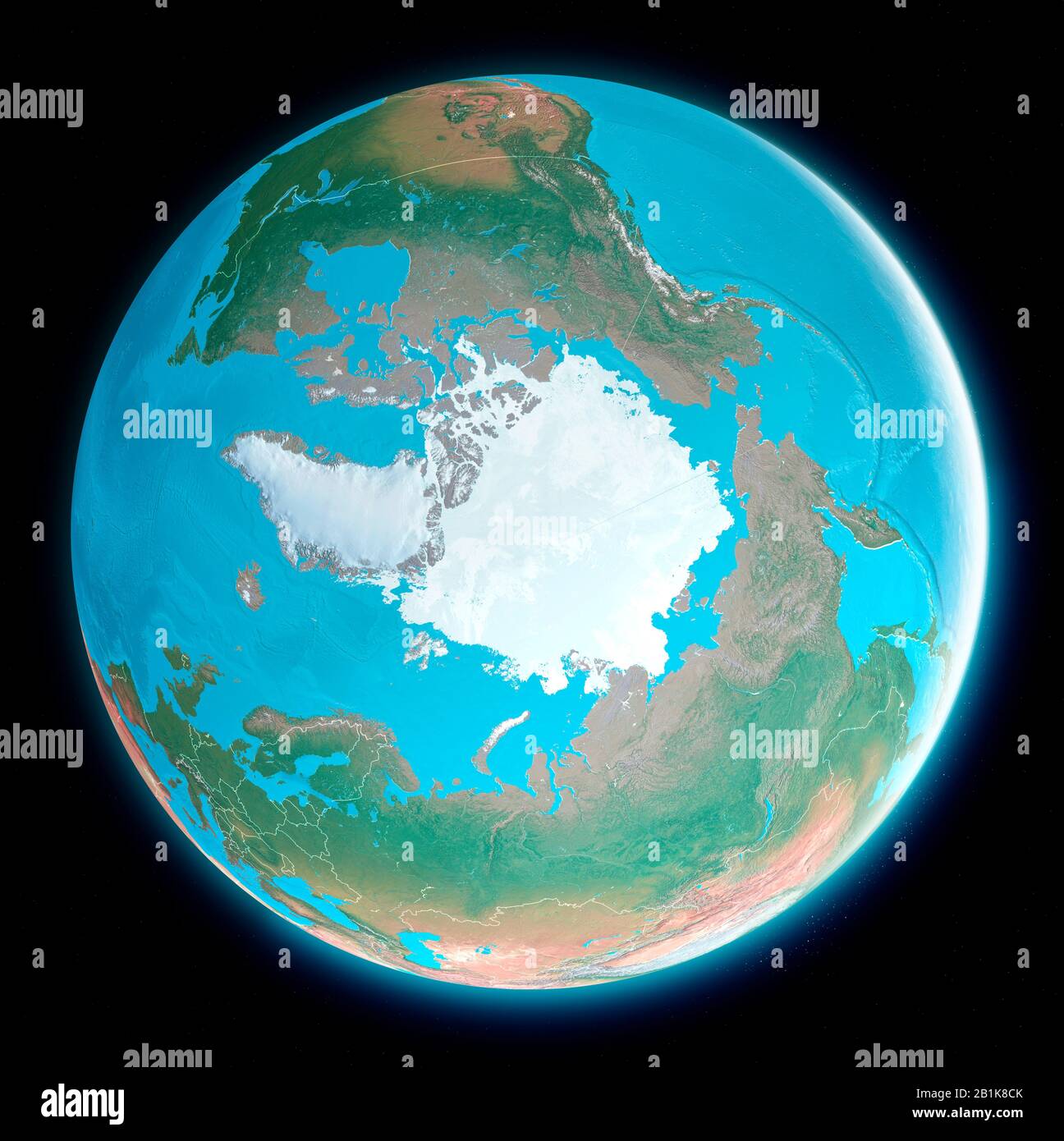

You’ve seen the images on Google Earth. Or maybe you've scrolled through a NASA gallery and thought you were looking straight down at the top of the world. Honestly, you probably weren't. Most people assume that satellite pictures of North Pole are easy to come by, like snapping a photo of your backyard from a drone. But the reality is way more complicated, glitchy, and, frankly, a bit of a mathematical headache for cartographers.

The North Pole isn't a solid landmass. It’s a shifting, groaning sheet of sea ice floating over an abyss. Because of how orbital mechanics work, many satellites don't actually fly directly over the 90-degree north mark. They miss it. They leave a "hole" in the data.

The Polar Gap and Why Maps Look Weird

For decades, there was a literal hole in our view of the world. Most Earth-observation satellites are in what we call sun-synchronous orbits. They zip around the planet from north to south, but because of the way the Earth bulges and the physics of gravity, they often tilt just enough to miss the absolute center. If you look at older mosaics of satellite pictures of North Pole regions, you’ll notice a perfect circle of "nothing" or a blur right at the top. This isn't a government cover-up or a secret entrance to a hollow earth. It’s just orbital inclination.

Space agencies like ESA (European Space Agency) and NASA have had to launch specific missions to fill these gaps. Think of the CryoSat-2 mission. It was specifically designed to orbit closer to the poles than previous birds. Why? Because we needed to know how thick the ice was, not just where it was.

It is mostly just ice and clouds

If you managed to get a live feed from a satellite looking at the pole right now, you’d probably be disappointed. It’s white. Sometimes it’s grey. Often, it’s just a thick blanket of clouds that doesn't move for weeks. Infrared sensors and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) are the real heroes here. SAR doesn't care about clouds or the six months of darkness that swallows the Arctic every winter. It bounces microwave signals off the surface to "see" the texture of the ice.

🔗 Read more: Calculating Age From DOB: Why Your Math Is Probably Wrong

That’s how we get those high-contrast, black-and-white images of ice leads—those giant cracks in the floes. Scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) spend their lives staring at these textures. They aren't looking for Santa; they are looking for the "marginal ice zone," which is where the real drama happens.

The Myth of the "Permanent" North Pole

People talk about the North Pole as a fixed destination. In reality, the ice you see in satellite pictures of North Pole today will likely be miles away by next week. The Transpolar Drift Stream is a massive ocean current that carries ice from the Siberian coast across the pole and down toward Greenland.

- Ice moves at a clip of several kilometers per day.

- Pressure ridges form when floes collide, creating jagged walls visible from high-res satellites like Maxar’s WorldView.

- Polynyas—open patches of water—can open up suddenly, even in the dead of winter.

I remember looking at a series of images from the MODIS instrument on the Terra satellite. From one day to the next, a lead hundreds of miles long just... opened. It looked like a vein on a leaf. If you were standing there with a GPS, you'd be moving while the "pole" stayed still beneath your feet.

High Resolution vs. Scientific Data

There is a huge difference between a "pretty" picture and a "useful" one. Companies like Planet Labs have hundreds of "Doves" (tiny satellites) that take photos of the Earth every single day. Their imagery is incredible for seeing ships or spotting a polar bear trek if the resolution is high enough. But for the North Pole, we need more than just pixels.

💡 You might also like: Installing a Push Button Start Kit: What You Need to Know Before Tearing Your Dash Apart

We need altimetry. NASA’s ICESat-2 is the gold standard here. It uses a green laser—yes, a literal space laser—to measure the height of the ice. It fires 10,000 pulses a second. By measuring the time it takes for that light to bounce back, we can figure out the ice thickness down to the centimeter. When you combine that with standard satellite pictures of North Pole areas, you get a 3D map of a disappearing world.

Why the colors look "fake"

If you’ve ever seen a satellite image where the ice looks bright blue or neon green, don't panic. It's "false color." Satellites "see" in wavelengths we can't. Shortwave infrared helps distinguish between snow, ice, and clouds, which all look identical to the human eye. In a standard photo, it's just a white blob. In false color, the old, thick "multi-year" ice shows up as a different shade than the thin, salty "first-year" ice.

This distinction is everything. Old ice is the "glue" of the Arctic. It’s thicker, fresher, and harder to melt. But our latest satellite data shows it's disappearing. We are moving toward "Blue Ocean Events," where the North Pole might be entirely ice-free during the summer. Satellite imagery is the only way we can track this in real-time without freezing to death in a tent.

The Tech Behind the Lens

We can't talk about these images without mentioning the RADARSAT Constellation Mission (RCM). Canada put these up because they have a massive stake in the Northwest Passage. These satellites use "circular polarization." It sounds fancy, but basically, it allows them to see through the most brutal Arctic storms.

📖 Related: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

When a ship is trying to navigate near the pole, they aren't looking at a pretty NASA photo from three days ago. They are using near-real-time SAR data. It’s grainy, it looks like static on an old TV, but it tells them where the "ice rubble" is. Rubble will tear a hull open. Smooth ice is just a Tuesday.

Common Misconceptions About Polar Imagery

- Google Earth is a live feed. It’s not. Most of the imagery you see at the pole is a composite of months or even years of data, smoothed out to look nice.

- You can see the Pole from any weather app. Most weather satellites (Geostationary) sit over the equator. They see the poles at such an extreme angle that the images are distorted and basically useless for detail.

- The "Black Hole" at the pole is a secret. Again, it's just the orbital path. As technology improves, that "hole" is shrinking, but it's still a logistical pain for mappers.

How to Find "Real" Pictures Yourself

If you’re tired of the polished, photoshopped versions of the Arctic, you should go straight to the source. The NASA Worldview tool is probably the coolest thing on the internet that nobody uses. It lets you layer live satellite data. You can toggle between "True Color," "Sea Ice Concentration," and even "Dust and Haze."

You can literally watch a storm spiral over the North Pole from yesterday’s pass. It’s raw. It’s messy. You’ll see the "data strips" where the satellite passed over and where it didn't. That’s what real science looks like.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Polar Imagery

If you want to move beyond being a casual observer and actually understand what you're looking at when you search for satellite pictures of North Pole, follow this workflow:

- Check the NASA Worldview site: Set the projection to "Arctic" (EPSG:3413). This centers the map on the North Pole so it’s not distorted by the usual flat-map logic.

- Look for the "Ice Edge": Instead of looking at the 90-degree mark, look at the edges near the Beaufort Sea or the Fram Strait. This is where the ice is actively breaking and moving.

- Compare seasons: Use the calendar tool to look at the same spot in September (the yearly minimum) versus March (the yearly maximum). The difference is staggering.

- Monitor the "Sentinel Hub": The Copernicus program offers free access to Sentinel-1 (radar) and Sentinel-2 (optical) data. If you want to see high-res cracks in the ice, this is the place.

- Verify the source: If you see a photo of a "hole" at the pole with clouds spiraling into it, it’s likely a storm or a composite error. Don't fall for the "hollow earth" clickbait.

The Arctic is changing faster than any other place on Earth. Satellites are our only eyes on a region that is too cold, too dark, and too remote for us to monitor any other way. By understanding how these images are made, you stop seeing just a white blob and start seeing a dynamic, breathing ecosystem that dictates the climate for the rest of us.