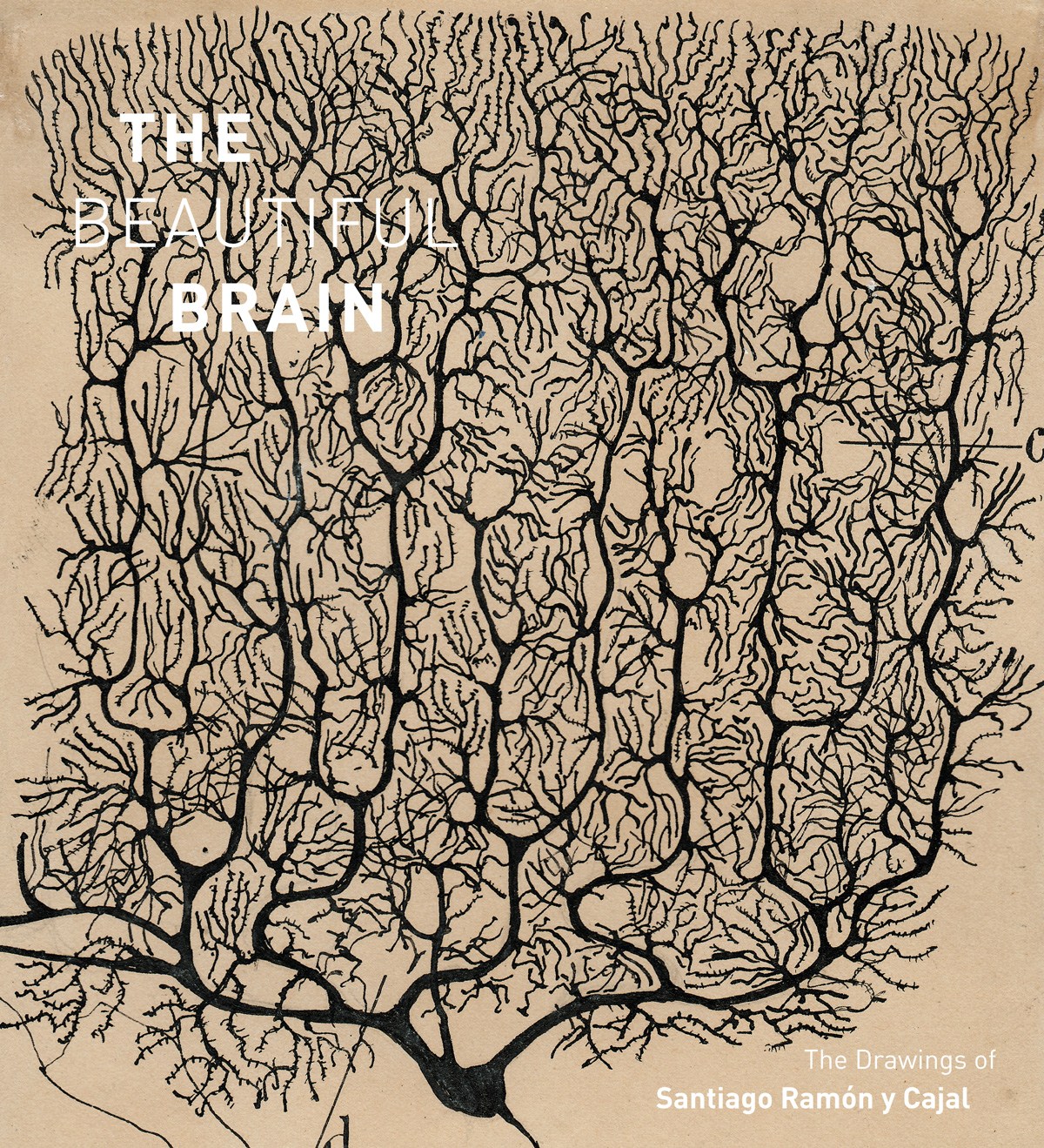

You’ve probably seen those beautiful, spindly drawings of brain cells that look like winter trees or tangled seaweed. Most people assume they’re just cool vintage art. In reality, they are the foundation of everything we know about how you think, feel, and breathe. They were drawn by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a man who was told he’d never amount to much because he was too busy getting into street fights and painting on walls he wasn't supposed to touch.

Honestly, Cajal is the most influential scientist you've probably never heard of. If Darwin explained where we came from, Cajal explained what we are—on a cellular level. He didn't just look through a microscope; he saw a "forest of neurons" where everyone else saw a giant, messy spiderweb.

The Kid Who Preferred Slingshots to Syllables

Santiago wasn't your typical "born genius." Born in 1852 in Petilla de Aragón, Spain, he was a nightmare for his teachers. He was rebellious. He was anti-authoritarian. He once got thrown into jail at age eleven for blowing up a neighbor’s gate with a homemade cannon.

His father, Justo Ramón, was a rigid anatomy professor who had zero patience for Santiago’s "frivolous" obsession with art. Justo wanted a doctor, not a painter. To "scare" the boy into medicine, Justo took him to graveyards at night to dig up human bones so Santiago could sketch them. Talk about a weird childhood. Ironically, this backfired in the best way possible. Santiago realized he could use his art to map the human body. He eventually traded his slingshot for a scalpel, but he never lost that rebellious streak.

Before he became the "Father of Neuroscience," he was a barber. Then a cobbler. Then an army medic in Cuba, where he caught malaria and tuberculosis and almost died. By the time he got back to Spain, he was a skeletal version of himself, but he had a drive that most people couldn't fathom. He bought a cheap, old microscope with his own meager savings.

🔗 Read more: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

The War of the Brain: Neuron vs. Reticulum

In the late 1800s, the scientific world was obsessed with "Reticular Theory." Basically, everyone—including the famous Italian scientist Camillo Golgi—thought the brain was one single, continuous, connected web. Like a giant plumbing system where everything flows together.

Why Everyone Was Wrong (Except Cajal)

The problem was that microscopes sucked back then. When you looked at brain tissue, it just looked like a blurry brown smudge. You couldn't see individual cells.

Then came the "Black Reaction." Golgi discovered that if you soaked brain tissue in silver nitrate, a few cells would turn pitch black, making them stand out. But Golgi still thought they were all physically fused together.

Cajal took Golgi's own method, tweaked it, and saw something different. He realized that neurons are individual units. They don't touch. There's a tiny gap between them.

💡 You might also like: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

- The Neuron Doctrine: Cajal’s big idea. Neurons are discrete cells.

- The Synapse: That tiny gap where the magic happens (though the term "synapse" came later from Charles Sherrington).

- Dynamic Polarization: The idea that signals only flow one way—in through the "branches" (dendrites) and out through the "trunk" (axon).

The 1906 Nobel Prize: The Most Awkward Dinner Ever

Imagine winning the highest honor in science and having to share it with your arch-nemesis who thinks your life's work is a lie. That’s exactly what happened in 1906. Santiago Ramón y Cajal and Camillo Golgi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

At the ceremony, Golgi went first. He used his speech to basically trash Cajal’s "individual cell" theory. He was bitter. He was stubborn. He refused to admit he was wrong, even though the evidence was literally staring him in the face.

Cajal, ever the class act, stood up afterward and delivered a speech filled with data, logic, and his incredible drawings. He didn't need to be mean; his work spoke for itself. He proved that the brain isn't a "blob"—it’s a sophisticated network of trillions of individual "messengers."

More Than Just a Science Guy

Cajal was a total polymath. He wasn't just sitting in a dark room with a microscope all day.

📖 Related: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

- Photography Pioneer: He was obsessed with it. He actually wrote one of the first books on color photography and figured out how to make his own plates.

- Science Fiction Writer: Under the pen name "Doctor Bacteria," he wrote stories about tiny people and futuristic inventions. Most were lost, but some still exist.

- Bodybuilder: Seriously. After getting bullied as a kid, he took up gymnastics and weightlifting. He was surprisingly buff for a guy who spent 15 hours a day staring at slides.

Why Should You Care in 2026?

We are currently in a "neuro-renaissance." Every time you hear about Elon Musk's Neuralink, or AI researchers talking about "neural networks," or doctors treating Alzheimer's, you're hearing the echoes of Cajal’s work.

He discovered the axonal growth cone, which is how nerves find their way during development. He was the first to suggest that the brain could change and grow—what we now call neuroplasticity. He basically predicted the future of medicine before we even had electricity in every home.

He died in 1934, still working. Even on his deathbed, he was reportedly making notes on his own symptoms. He was a scientist until the very last breath.

How to Apply the "Cajal Mindset" to Your Life

If you want to think like the man who mapped the mind, here’s the blueprint:

- Look closer than everyone else. Most scientists saw a mess; Cajal saw a map. Don't accept the "obvious" answer.

- Combine your "useless" hobbies. Cajal's art and photography weren't distractions—they were his secret weapons. Your weird side-interest might be the thing that makes you a pro at your "real" job.

- Trust the data, not the crowd. Everyone believed Golgi because he was the "big name." Cajal believed his own eyes.

- Embrace the "fury" of work. He famously worked "with a fury," often spending 15 hours straight at his desk. Deep work isn't a new concept; it's how great things get done.

Next Steps for You:

If you want to see his actual work, look up the "Cajal Legacy" archives at the Cajal Institute in Madrid. Better yet, pick up a copy of his book Advice for a Young Investigator. It’s surprisingly funny, very salty, and still the best guide ever written for anyone trying to discover something new in a world that thinks it already knows everything.