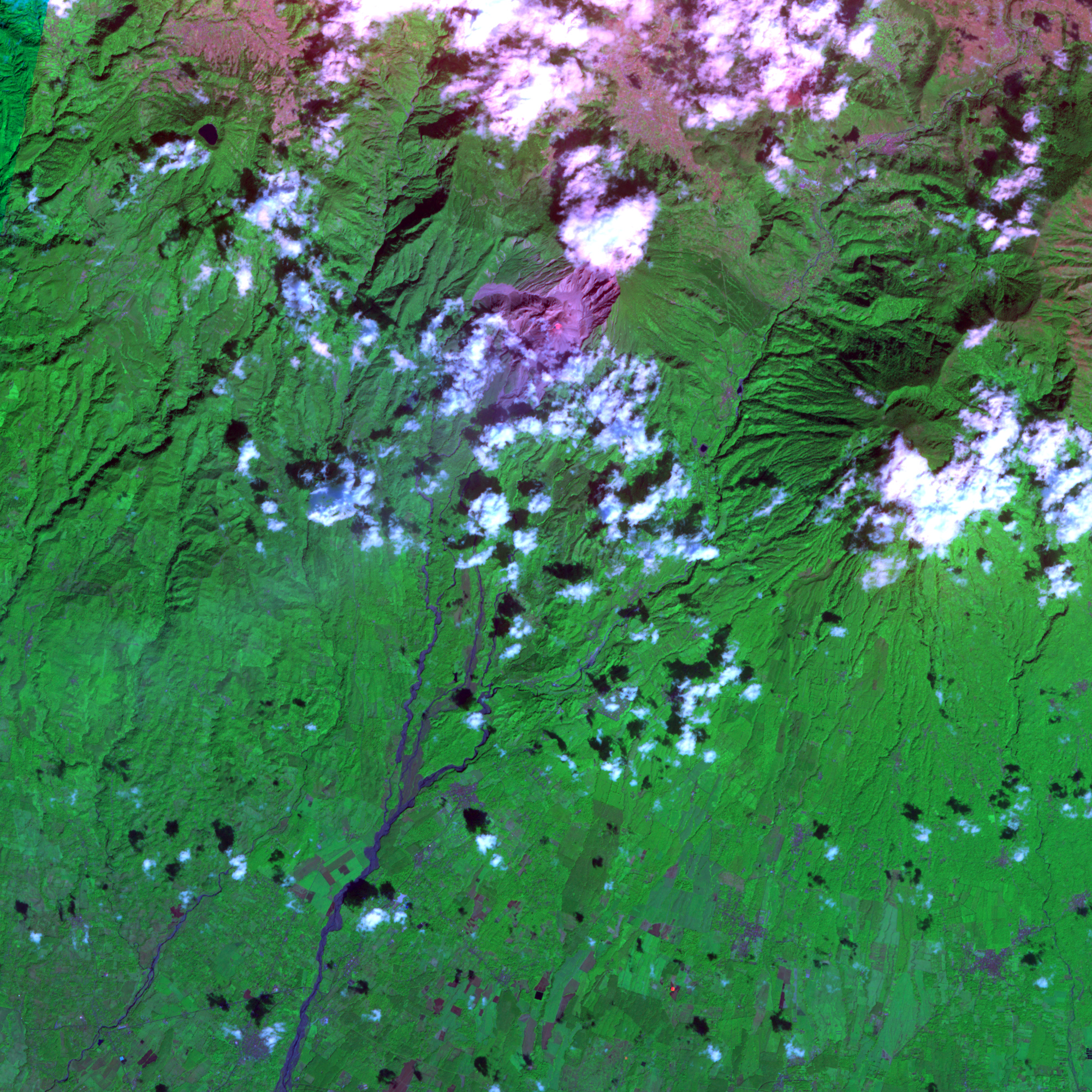

Standing on the ridge of Siete Orejas at dawn, you see it. A perfect, terrifying cone silhouetted against a bruised purple sky. That’s Santa Maria. It looks peaceful from a distance, almost like a postcard from the Swiss Alps, but don't let the symmetry fool you. This is one of the most volatile landscapes on the planet. Most people come to Guatemala for the markets in Chichicastenango or the colonial ruins of Antigua, but if you're a certain kind of person—the kind who likes their scenery with a side of geological peril—the Santa Maria volcano is the real reason to visit the Western Highlands.

It's massive.

The peak towers at 3,772 meters above sea level, looming over the city of Quetzaltenango (Xela). While it isn't currently puffing out smoke itself, its younger, angrier sibling, Santiaguito, is doing enough work for both of them. This isn't just another hike. It’s a lesson in how quickly the earth can change.

The 1902 Explosion: A History Written in Ash

Most people think of the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens as the big one. Honestly? Compared to what happened at Santa Maria in 1902, St. Helens was a localized event. For over 500 years, Santa Maria had been quiet. Local indigenous communities and the growing coffee industry in Quetzaltenango didn't even realize it was a volcano; many just thought it was a large mountain. That changed in October 1902.

The explosion was catastrophic. It was a VEI 6 event—Volcanic Explosivity Index—putting it in the same league as Krakatoa. It blasted a gaping, two-kilometer-wide crater into the southwestern flank of the mountain. Imagine a mountain just losing its entire side in a matter of hours. The ash didn't just cover Xela; it was detected as far away as San Francisco.

The numbers are grim. Estimates suggest at least 5,000 people died, though the true number is likely much higher because census data for the surrounding rural villages was nonexistent at the turn of the century. Most died from the weight of ash collapsing their roofs or from the subsequent outbreaks of malaria and food shortages. It wasn't just a disaster; it was the end of an era for the region's economy.

💡 You might also like: Wingate by Wyndham Columbia: What Most People Get Wrong

Understanding the Santiaguito Complexity

You can't talk about Santa Maria without talking about the "parasitic" dome complex at its feet. Since 1922, the 1902 crater has been home to Santiaguito. This isn't a single peak but a series of dacitic lava domes that are constantly growing, collapsing, and exploding.

Scientists from the INSIVUMEH (Guatemala's national institute for seismology and volcanology) keep a nervous eye on this place 24/7. Why? Because Santiaguito is one of the world's most active volcanoes. It doesn't just erupt every few years; it erupts almost every hour.

Why the Domes are Dangerous

Unlike volcanoes that flow like rivers of fire (think Hawaii), the magma here is thick. Sticky. It’s high in silica. Because the gas can’t escape easily, pressure builds until the dome literally pops. This creates pyroclastic flows—superheated clouds of gas and rock that move at hundreds of kilometers per hour. If you’re standing in the wrong place when one of these lets go, there is no running away. You basically just turn to ash.

Climbing Santa Maria: What the Guides Won't Tell You

If you’re planning to summit, you need to know that the "classic" route is a total grind. You start in the village of Llanos del Pinal. It’s a sleepy place where kids play soccer on dust lots and everyone seems to be carrying a machete for agricultural work.

The hike is basically a 1,200-meter vertical gain over about five kilometers. It’s steep. Really steep. You’re walking through high-altitude cloud forest, which is beautiful until it starts raining—and in the Guatemalan Highlands, it rains often. The trail is frequently a muddy mess of slippery roots and loose volcanic scree.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: The Sky Harbor Airport Map Terminal 3 Breakdown

Pro Tip: Do not attempt this without a guide. Not because you'll get lost—the trail is fairly obvious—but because of security. Banditos have been known to frequent the lower slopes, targeting solo hikers with expensive camera gear. Joining a group from an outfit like Quetzaltrekkers isn't just about safety, though; the proceeds usually go to local orphanages, so you're doing some good while you sweat.

The View from the Top (and the Smell)

Reaching the summit is a surreal experience. You'll likely find local Maya groups performing ceremonies at the top. They leave offerings of flowers, candles, and sometimes chocolate. It’s a reminder that while tourists see a "feature" to be conquered, the locals see a living deity. Respect that. Don't go trampling through their ritual circles for a selfie.

Looking down from the summit into the 1902 crater is where the real show happens. You're looking directly down onto the active vents of Santiaguito. Every 45 to 60 minutes, a plume of gray ash shoots into the air. You hear it before you see it—a sound like a jet engine starting up. Then the "boom" hits your chest.

It’s tempting to try and hike down into the crater to get closer to the action.

Don't.

Just don't do it.

People have died from sudden gas releases or falling rocks. Stay on the rim. The view from 3,700 meters is plenty close enough.

Navigating the Microclimates

The weather here is schizophrenic. You'll start the hike in shorts and a t-shirt, sweating through the humid forest. By the time you hit the "La Meseta" plateau, the wind picks up. At the summit, the temperature can drop to near freezing, especially if the "chipichipi" (a fine, freezing mist) rolls in.

👉 See also: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

- Pack layers. Merino wool is your best friend here.

- Bring at least 3 liters of water. There are no reliable sources once you leave the village.

- Sunscreen is mandatory. At this altitude, the tropical sun will peel your skin off even if it feels cold.

The Geopolitical Side of the Volcano

It’s easy to look at Santa Maria as just a natural wonder, but it’s deeply tied to the social fabric of Quetzaltenango. The volcanic soil is why the coffee here is so damn good. The minerals from centuries of ash deposits create a flavor profile that’s acidic and chocolatey, highly prized by roasters in Seattle and London.

But there's a cost. The people living in the shadow of the volcano, particularly in the "Palajunoj Valley," live in constant fear of lahars. These are volcanic mudslides that happen when heavy rains mix with fresh ash. They can wipe out an entire village in minutes. The government in Guatemala City often ignores these rural areas, leaving the local communities to build their own early warning systems using nothing but cell phones and sirens.

Common Misconceptions

People often confuse Santa Maria with its more famous cousin, Fuego, near Antigua. While Fuego is the "Instagram" volcano because of its spectacular nighttime lava fountaining, Santa Maria is more "academic" and brooding. You won't see rivers of red lava here. You’ll see gray ash, massive stone domes, and a landscape that feels like it belongs on the moon.

Another myth is that the volcano is "due" for another 1902-style eruption. Volcanoes don't really work on a schedule. While the constant activity at Santiaguito keeps the pressure from building up to a massive 1902 level, the risk of a dome collapse causing a catastrophic lateral blast is always there.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

If you're actually going to do this, here is the non-nonsense checklist:

- Acclimatize in Xela first. Spend at least three days in Quetzaltenango (2,330m) before attempting the summit. If you fly from sea level and try to hike the next day, you will get altitude sickness. It feels like a hangover mixed with a migraine. It’s miserable.

- Hire a local guide. Check out Thrive Maya or Quetzaltrekkers. Expect to pay around $40-$60 USD for a day hike.

- Check the INSIVUMEH reports. They post daily bulletins on volcanic activity. If they report "increased seismic activity" or "pyroclastic flows," stay home.

- Gear up correctly. You need boots with actual grip. Sneakers will get shredded by the volcanic rock.

- Leave early. Start at 4:00 AM or 5:00 AM. By noon, the clouds usually roll in and block the view of Santiaguito, which defeats the whole purpose of the climb.

Santa Maria isn't a theme park. It’s a raw, shifting part of the Earth’s crust that doesn't care about your hiking schedule. Treat it with the respect a 100-year-old killer deserves, and it will give you the most incredible view in Central America. Be careless, and you're just another statistic in a long history of people who underestimated the Western Highlands.