Imagine living on a giant, flat-topped iceberg that never melts, except the "iceberg" is actually a massive nunatak—a mountain peak poking through a glacial shield. That is the daily reality for the small crew at SANAE IV, the current South African Antarctic station. Most people think of Antarctica and immediately picture the Americans at McMurdo or the British at Halley. South Africa usually doesn't even enter the conversation. But honestly, the South African National Antarctic Expedition (SANAE) has been quietly running one of the most sophisticated research hubs on the frozen continent since the late 1950s.

It's cold. Brutally so.

We are talking about Vesleskarvet in Queen Maud Land. The station sits perched on a rocky cliff about 200 kilometers away from the actual coast. This isn't your typical polar base. While many stations are buried under the snow or sitting on moving ice shelves that eventually crumble into the sea, SANAE IV was built to last. It’s an orange-and-blue fortress on stilts.

The Weird History of South Africa's Frozen Footprint

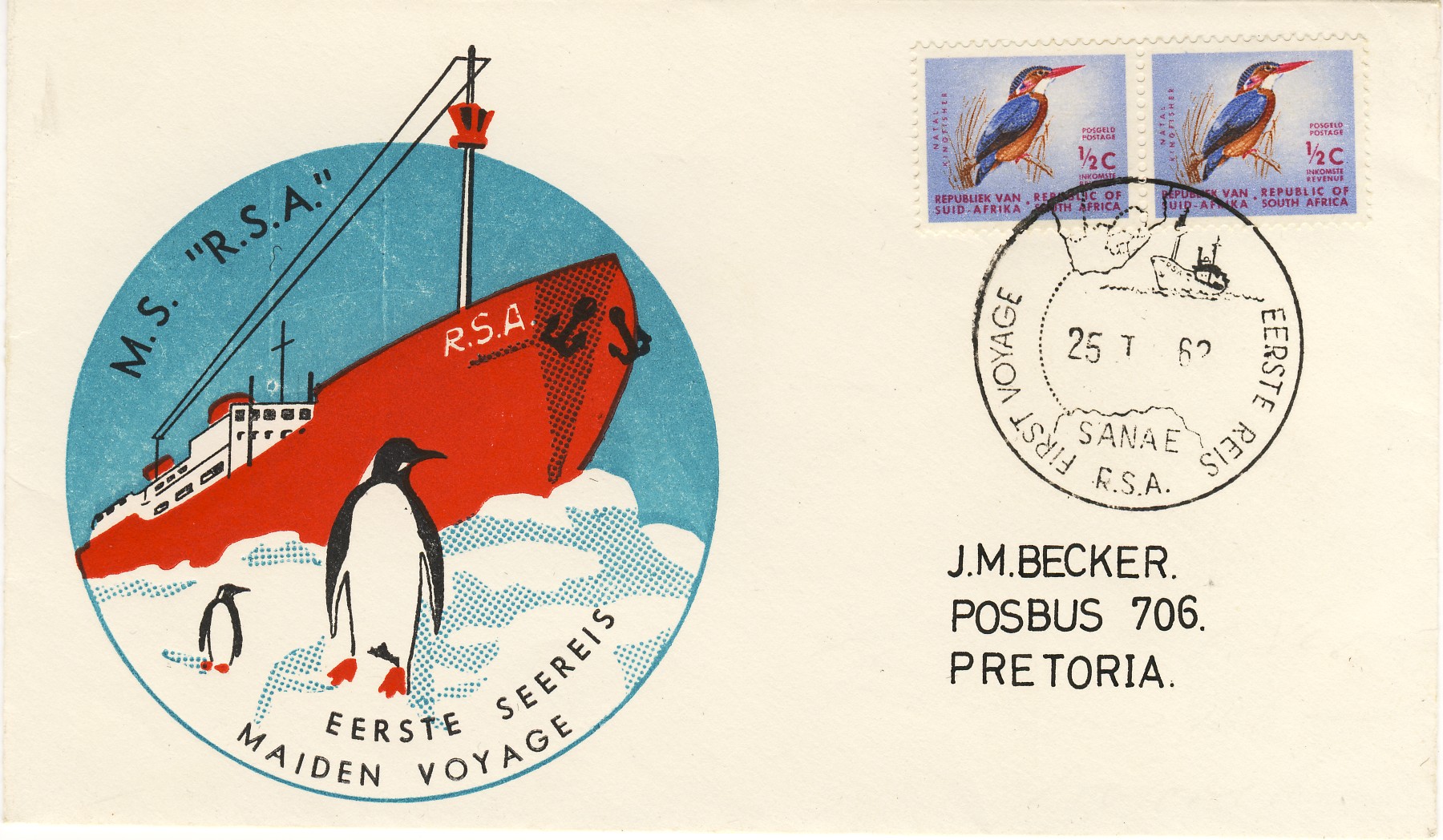

South Africa didn't just wake up one day and decide to go to the South Pole. It started with Hannes la Grange. He was the first South African to reach the Pole in 1958 as part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Shortly after, the South African government took over a vacant Norwegian base (Norway Station). They called it SANAE I.

It was basic.

The first three iterations—SANAE I, II, and III—were all built on the Fimbul Ice Shelf. If you know anything about glaciology, you know that building on an ice shelf is basically setting a timer on your own destruction. The snow accumulates, the weight crushes the structures, and the ice slowly flows toward the ocean. By the time SANAE III was decommissioned, it was buried deep beneath the surface, a claustrophobic maze of tunnels that was eventually destined to become an iceberg.

Engineers got tired of digging.

So, in the mid-90s, they moved inland. They found Vesleskarvet. By building on solid rock (a nunatak), they eliminated the "burial" problem. The South African Antarctic station as we know it today was completed in 1997. It looks like a series of interconnected pods held up by massive steel legs. The wind screams underneath the belly of the building. This prevents snow from drifting and burying the facility. Smart, right?

🔗 Read more: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

What Actually Happens Inside SANAE IV?

You might think it's just a bunch of people sitting around drinking coffee and looking at penguins. It’s not. In fact, there aren't even many penguins that far inland. It’s a desert.

The South African National Antarctic Programme (SANAP) focuses heavily on the "invisible" stuff. Space weather is a huge deal here. Because of the Earth’s magnetic field lines, the polar regions are like open windows into the magnetosphere.

- SuperDARN Radar: This is part of an international network. It tracks high-frequency radar beams to study the upper atmosphere.

- VLF Radio Waves: Researchers monitor Very Low Frequency emissions to understand how solar flares affect our satellite communications.

- Seismology: They track the earth’s crust movements from a place where there is zero "human noise."

Dr. Pierre Cilliers and other scientists from the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) have spent years documenting how the sun interacts with our atmosphere. If a massive solar storm ever knocks out the world's GPS and power grids, the data gathered at the South African Antarctic station will likely be what helped us predict it.

It's not all high-tech sensors, though. There’s the human element.

The "winter-over" team usually consists of about 10 people. A doctor, a couple of diesel mechanics, an electronics engineer, and various scientists. They are trapped there for over a year. Once the last ship (the S.A. Agulhas II) leaves in February, nobody is coming to get them until the following December. There is no "quick flight" out. If your appendix bursts in July, the base doctor is doing surgery on the dining table while the rest of the crew holds the flashlights.

Life on the Edge of the World

Let’s be real: the isolation is the hardest part. You've got the "Mid-Winter" celebrations in June, which is a tradition across all Antarctic stations, but mostly it's just work and maintenance. The diesel mechanics are arguably the most important people on the base. If the generators fail, the station dies. It’s that simple.

Water is another headache. You can't just turn on a tap. You have to melt snow. Every day, the crew has to ensure the "smelter" is fed. They use a bulldozer to dump snow into a massive heated tank.

💡 You might also like: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

Then there's the food. You've got "freshies"—fresh fruit and veg—for the first month. After that? It's frozen or canned everything. You haven't lived until you've seen a grown man get excited over a slightly bruised apple found at the bottom of a crate in August.

The South African Antarctic station is also a bit of a diplomatic chess piece. South Africa is an original signatory of the Antarctic Treaty. This gives them a "seat at the table" when it comes to the future of the continent. While other nations are eyeing Antarctica for potential minerals or fishing rights (though currently banned), South Africa maintains its presence to ensure the "Peace and Science" mandate of the treaty stays intact.

Why You Should Care About Queen Maud Land

This specific slice of Antarctica is claimed by Norway, but the treaty puts those claims on ice. Literally. The South African station serves as a hub for several other nations. Often, German or Finnish scientists will pass through. It’s a logistics nightmare managed by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE).

They use the S.A. Agulhas II, a world-class polar research vessel. This ship is a beast. It's a mobile laboratory, a tanker, and a passenger ship rolled into one. When it docks at the ice shelf—called "the E-Base"—the offloading process is a 24-hour-a-day operation. They have to move tons of fuel and supplies across the ice before the weather turns.

Technical Specs and Survival

The station is designed to handle winds exceeding 200 kilometers per hour. The walls are made of sandwich panels—fiberglass-reinforced polyester with a thick foam core. If you touch the outside wall without a glove during winter, you’re losing skin.

Inside, it’s surprisingly cozy. There are bedrooms, a gym, a sauna (essential for morale), and a massive kitchen. But you can never forget where you are. Every time you walk to the "Power Hut" or the "Science Block," you are crossing a bridge that separates you from certain death.

One of the coolest—and most terrifying—things about SANAE IV is the silence. On a calm day, the silence is so heavy it feels like it’s pressing against your ears. There is no rustle of leaves. No distant traffic. Just the sound of your own heartbeat.

📖 Related: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

Common Misconceptions

People often ask if you can visit. Technically, yes, but practically, no. This isn't a cruise destination like the Antarctic Peninsula. This is the "Deep South." There are no luxury hotels here. If you want to see the South African Antarctic station, you usually have to be a researcher or a highly skilled tradesperson.

Another myth is that it's always dark. It’s not. In summer, the sun just circles the sky. It never sets. You lose all sense of time. People start working 20-hour shifts because their brains don't tell them to sleep. Then, in winter, the sun vanishes for months. That’s when the "Polar T3" syndrome kicks in—a sort of cognitive fog caused by disrupted thyroid hormones and the lack of light.

Making Sense of the South African Antarctic Station

Why does South Africa keep spending money on this?

It's expensive. It's dangerous. It's thousands of miles away from Cape Town.

The answer is twofold: Prestige and Protection. South Africa is the only African nation with a permanent presence in Antarctica. This is a massive point of pride for the scientific community in the Global South. Furthermore, the Southern Ocean drives the weather patterns for the entire African continent. If we don't understand what’s happening at the South African Antarctic station, we can't accurately predict droughts or floods in the Free State or Limpopo.

It is a massive thermometer for the planet.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you're fascinated by the South African Antarctic station, don't just stop at a Wikipedia page. Here is how you can actually engage with this world-class research:

- Follow the ALSA Archive: The Antarctic Legacy of South Africa (ALSA) has an incredible digital archive of photos, diaries, and maps from the 1950s to today. It is the best place to see the human side of the missions.

- Check SANSA's Real-Time Data: The South African National Space Agency often shares live feeds of magnetosphere data collected at SANAE IV. If you see a spike in their graphs, look for auroras in the following days.

- Monitor the S.A. Agulhas II Schedule: The ship's departures from Cape Town (usually in December) are often public events. If you're in the Western Cape, you can sometimes see the vessel docked at the Waterfront.

- Study the Careers: SANAP is always looking for specialized skills. They don't just need PhDs; they need electricians, plumbers, and mechanics who can handle extreme environments. If you’re a tradesperson looking for the ultimate adventure, keep an eye on DFFE recruitment cycles.

The station isn't just a building. It's a testament to what humans can do when they stop fighting over borders and start looking at the stars and the ice. It’s South Africa’s most isolated outpost, and in many ways, its most important one.