Tax season is usually a headache, but when you start seeing a sample Form 1099-DIV pop up in your brokerage account or mailbox, things get a little more specific. It isn't just a random piece of paper. Honestly, it’s the trail of breadcrumbs the IRS uses to make sure they get their cut of your investment income. If you own stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs in a taxable brokerage account, you’re going to deal with this form eventually.

Basically, the 1099-DIV is what banks and financial institutions use to report the dividends and distributions paid out to you during the year. You might think, "I only made fifty bucks, does it even matter?" Actually, the threshold is pretty low. If you received at least $10 in dividends or distributions, the payer is required to send you this form. It sounds like a tiny amount, but the IRS is remarkably pedantic about these things.

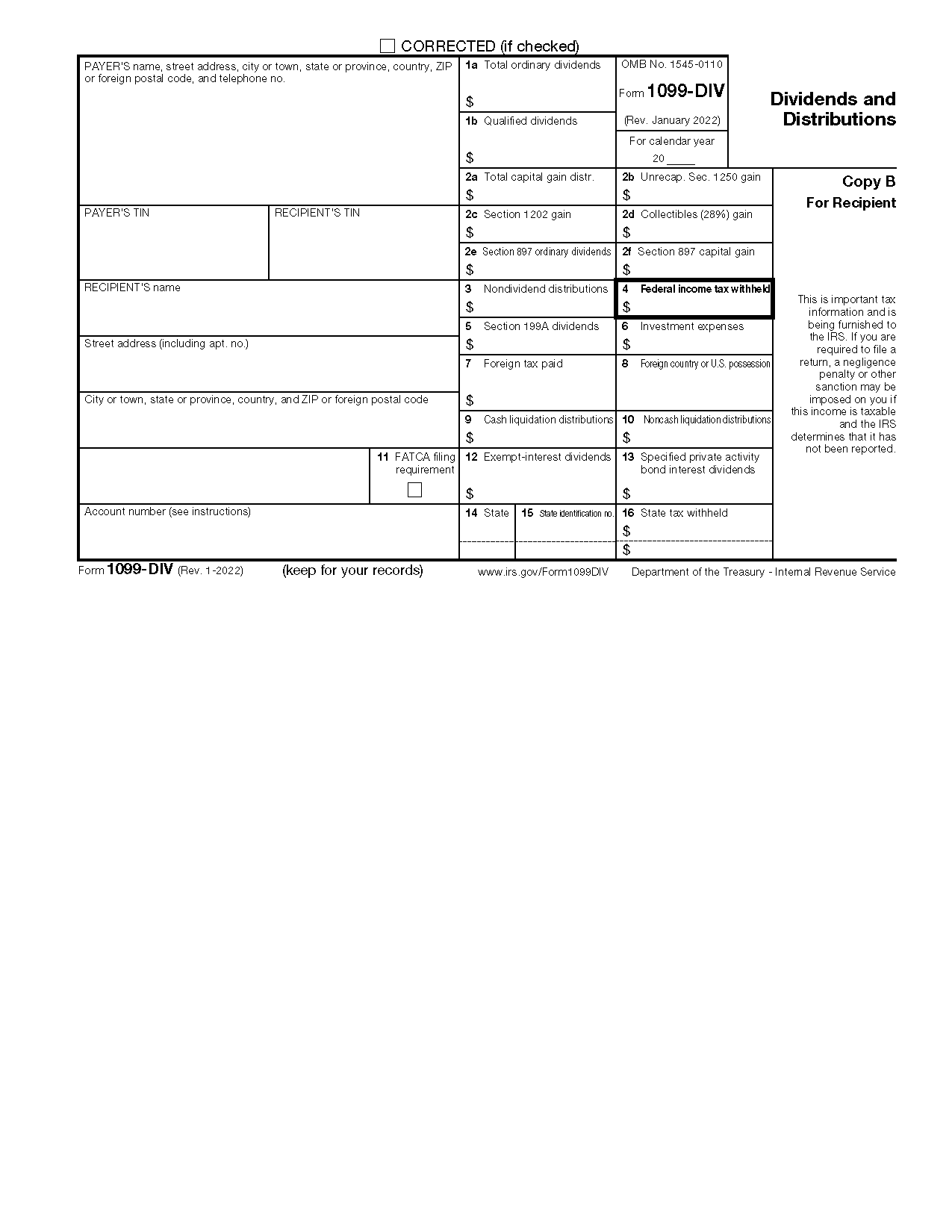

Looking at a sample Form 1099-DIV for the first time is overwhelming because of all the boxes. Box 1a, Box 1b, Box 2a—it feels like a math quiz you didn't study for. But once you break it down, it's really just a story about how your money made more money.

Decoding the Boxes on a Sample Form 1099-DIV

The most important part of any sample Form 1099-DIV is distinguishing between ordinary dividends and qualified dividends. This is where most people trip up.

📖 Related: New York City Average Income: Why the Numbers Feel So Weird

In Box 1a, you’ll see "Total Ordinary Dividends." This is the gross amount of all dividend distributions you received. However, Box 1b is the one you really want to pay attention to: "Qualified Dividends." These are special. Why? Because qualified dividends are taxed at the lower capital gains rates rather than your standard income tax rate. If you’re in a high tax bracket, that difference is massive. To qualify, you generally have to hold the stock for more than 60 days during the 121-day period that begins 60 days before the ex-dividend date. It’s a bit of a mouthful, but your brokerage usually does that math for you.

Then there is Box 2a, "Total Capital Gain Distributions." You often see this with mutual funds. Even if you didn't sell a single share of your fund, the fund manager might have sold some of the internal holdings for a profit. They pass that profit on to you, and unfortunately, you have to pay taxes on it. It’s one of those "hidden" tax hits that catches people off guard in April.

The Weird Stuff in the Other Boxes

Sometimes you'll see amounts in Box 7, which covers "Foreign Tax Paid." If you own an international fund or a company based in, say, Germany or Japan, they might have withheld taxes in their own country first. You don't want to be double-taxed. That's why you can often claim a foreign tax credit on your own return. It's a small win, but every dollar counts.

Box 5 is another one that has become more relevant lately: "Section 199A dividends." This usually relates to Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Because of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, these distributions might qualify for a 20% deduction. If you’re seeing numbers in Box 5, don’t just ignore them; they are actually there to help lower your tax bill.

🔗 Read more: US Dollar to Moroccan DH: What Most People Get Wrong About Exchanging Money

Why the Sample Form 1099-DIV Looks Different at Every Bank

If you have accounts at Vanguard, Fidelity, and Charles Schwab, you might notice that your 1099s don't look exactly like the official IRS "Copy B." Banks often use "Substitute Forms."

These are consolidated statements. They pile your 1099-INT, 1099-DIV, and 1099-B all into one giant PDF. It’s convenient, sure, but it makes finding the specific sample Form 1099-DIV data a bit of a scavenger hunt. You have to look for the section specifically labeled "1099-DIV Information."

One thing that confuses a lot of folks is the "Nondividend Distributions" in Box 3. This is often called a "Return of Capital." It’s not actually income. It’s the company giving you back a portion of your original investment. You don't pay taxes on this now, but it does lower your "cost basis." That means when you eventually sell the stock, your capital gain will be higher. It’s a game of "pay me now or pay me later."

Real-World Examples of 1099-DIV Surprises

Let's talk about the "Wash Sale" trap. While that usually lives on the 1099-B, it can influence how dividends are handled if you are day trading. Or consider the "Ex-Dividend Date." If you bought a stock one day too late, you won't see that dividend on your 1099-DIV, even if you owned the stock for most of the month.

🔗 Read more: Why the Ford Sharonville Transmission Plant Still Matters to the American Road

I remember a client who was furious because they received a 1099-DIV for a "liquidating distribution" in Box 9. Their company had gone bankrupt and was paying out the remaining scraps to shareholders. They thought it was a dividend. It wasn't. It was a return of investment that signaled the end of that stock's life.

Common Misconceptions About Dividend Reporting

Many people think that if they reinvest their dividends (DRIP), they don't have to pay taxes on them. This is totally wrong. Even if you never touched the cash and it went straight back into buying more shares, the IRS views that as you receiving the cash and then choosing to buy more stock. You still owe the tax. The sample Form 1099-DIV will show the full amount regardless of whether it stayed in the account or went into your pocket.

Another myth? That 1099-DIVs are only for wealthy investors. If you have a simple Acorns account or a Robinhood portfolio and you’ve made more than $10 in dividends, you’re getting one.

How to Check for Errors

Yes, banks make mistakes. It happens more often than you’d think, especially with cost basis reporting or qualified dividend status.

- Compare your year-end monthly statement to the 1099-DIV.

- Check if the "Payer's Federal ID Number" matches previous years.

- Verify that "Federal Income Tax Withheld" (Box 4) is zero unless you specifically requested backup withholding.

If you find a mistake, you have to ask the broker for a Corrected 1099-DIV. Don't just change the numbers on your tax return. The IRS computers will flag the discrepancy immediately because they receive a copy of whatever the broker sends you.

Handling the Form During Tax Filing

When you're plugging this into software like TurboTax or H&R Block, most of the time you can just import the data directly from your brokerage. It’s a lifesaver. But you still need to eyeball the "Qualified" vs "Ordinary" split. If the software doesn't pick up Box 1b correctly, you could end up paying way more in taxes than necessary.

For those doing it by hand (bless your soul), ordinary dividends go on Form 1040, Line 3b. Qualified dividends go on Line 3a. They are kept separate so the tax software can apply the special capital gains tax worksheet to the qualified portion.

Actionable Steps for Managing Your 1099-DIVs

Don't wait until April 14th to look at these. Most brokerages release them in mid-February, but they frequently issue "Amended" versions in March.

- Wait for the "Final" Statement: If you own complex instruments like REITs or certain ETFs, wait until late February or early March to file. These entities often reclassify their dividends at the last minute, triggering an amended 1099.

- Organize by Account: Keep a folder specifically for "Taxable Income." Remember, you won't get a 1099-DIV for your 401(k) or IRA because those are tax-advantaged.

- Check Box 4: If there is a number in "Federal income tax withheld," it means you might be subject to backup withholding. This usually happens if you haven't provided the bank with a correct W-9 or Social Security Number. You'll want to fix that for next year so you can keep your cash throughout the year.

- Review Box 10: This is for "Exempt-interest dividends" from municipal bonds. While these are usually free from federal tax, they might still impact your Social Security taxation or the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).

Understanding the nuances of a sample Form 1099-DIV is basically about keeping more of your money. By knowing which boxes represent "free" tax breaks (like qualified dividends) and which ones represent potential pitfalls (like capital gain distributions), you can plan your portfolio much more effectively. Keep the form even after you file; the IRS recommends keeping tax records for at least three years, though seven is safer if you want to be extra cautious about audits.