You’re sitting on your porch, watching the sky turn that weird, bruised shade of purple. The local news anchor is frantic, pointing at a swirling mass on the radar. "It's a Category 2," they say. You breathe a sigh of relief. You stayed for a Cat 2 three years ago, and it just knocked over some patio furniture and killed the power for a day. No big deal, right?

Honestly, that kind of thinking is exactly what keeps emergency managers up at night.

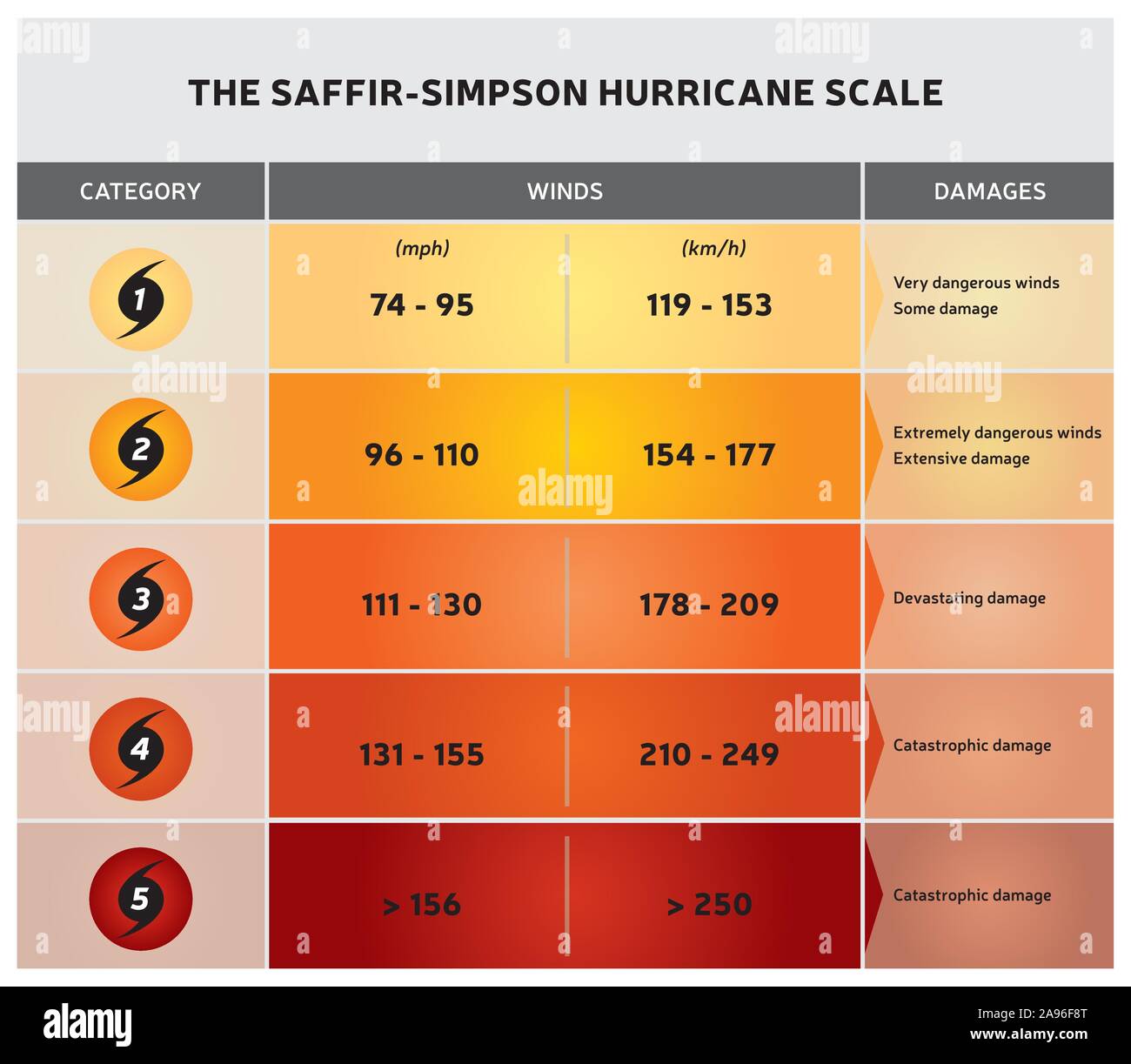

The Saffir Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is probably the most famous tool in meteorology, but it’s also the most misunderstood. We see that number—1 through 5—and we think we know the whole story. But that number is only telling you how fast the wind is blowing. It’s not telling you how deep the water will get in your living room or if a tree is going to slice your house in half.

Basically, the scale is a structural engineering tool disguised as a weather report.

The Secret History of the Scale

In the early 1970s, a structural engineer named Herbert Saffir was working on a project for the UN. He wanted to categorize how winds affected buildings. He realized there wasn't a good way to describe it. He teamed up with Robert Simpson, who was the director of the National Hurricane Center at the time.

Simpson added the "water" part—the storm surge and pressure. For decades, that’s what we used. But in 2010, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) did something controversial. They stripped the water out. They turned it into the Saffir Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale we use today, focusing purely on "1-minute maximum sustained wind speeds."

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Why? Because water is messy.

Storm surge depends on the shape of the coastline, how shallow the water is, and the size of the storm. Wind is easier to measure. But this change created a dangerous gap in how we perceive risk. You can have a Category 1 storm like Hurricane Florence (2018) that dumps 30 inches of rain and causes billions in damage, while a tiny Category 3 might just whistle through with a few broken windows.

Breaking Down the Categories (The Real Version)

When we talk about these categories, don't think of them as a linear ladder. It's more like a "damage multiplier." A Category 2 storm doesn't do twice the damage of a Category 1. It does about 10 times the damage.

Category 1: 74-95 mph

People call these "minor" storms. Tell that to someone whose roof shingles just got peeled off like a banana. You’ll see gutters sag, vinyl siding fly away, and shallow-rooted trees (looking at you, pine trees) tip over. Power outages? Definitely. Plan for a few days of living by candlelight.

Category 2: 96-110 mph

This is where things get "extremely dangerous." We’re talking about "near-total power loss." In a Cat 2, those well-constructed frame homes you see in suburban neighborhoods start taking major hits to the roof and siding. If you have an old oak tree in your yard, it’s probably going to end up on your car.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Category 3: 111-129 mph

The NHC calls this a "Major Hurricane." This is the threshold where structural damage becomes "devastating." Gable ends of houses can blow out. Electricity and water will likely be gone for weeks. If you’re in a mobile home, you shouldn't even be reading this—you should have left yesterday.

Category 4: 130-156 mph

Catastrophic. That’s the only word. You’re looking at the loss of most of the roof structure and some exterior walls. Most of the trees in the area will be snapped or uprooted. Residential areas will be isolated because the roads will be a graveyard of power poles and timber. It might be uninhabitable for months.

Category 5: 157 mph or Higher

Total destruction. A high percentage of framed homes will be completely destroyed. It’s not just about the wind anymore; it’s about the fact that most buildings aren't designed to withstand a 160 mph gust for more than a few seconds.

The "Category 6" Debate

Lately, there's been talk in the scientific community, specifically from researchers like Michael Wehner and James Kossin, about adding a Category 6.

Since the scale is "open-ended," anything above 157 mph is a Category 5. But with climate change warming the oceans, we're seeing storms hit 180, 190, even 200 mph (like Hurricane Patricia in 2015). Scientifically, a 190 mph storm is vastly more destructive than a 157 mph one. However, the NHC argues that a "6" is unnecessary because, at that point, everything is already destroyed.

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

If your house is gone at 160 mph, does it matter if the wind was actually 190?

What the Scale Doesn't Tell You

If you only look at the Saffir Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, you’re missing the two biggest killers:

- Storm Surge: This is the "mound" of water the wind pushes onto land. Hurricane Ike was a Category 2 at landfall, but its surge was 20 feet high. It wiped the town of Gilchrist, Texas, off the map.

- Inland Flooding: Slow-moving storms are the worst. Hurricane Harvey was a beast, but the wind wasn't what paralyzed Houston—it was the 50+ inches of rain.

The scale doesn't care if a storm is moving at 2 mph or 20 mph. But you should. A slow Category 1 is often more dangerous than a fast Category 3.

How to Actually Use This Information

So, the next time you see a hurricane category on the news, don't just look at the number.

- Check the "Wind Radius": Is it a tiny, tight storm or a massive one? Huge storms (like Sandy) have way more "reach" for surge, even if their winds are lower.

- Look at the Forward Speed: If it’s moving slower than 10 mph, expect catastrophic flooding regardless of the category.

- Ignore the "Weakening" Hype: If a Cat 4 weakens to a Cat 2 right before landfall, the water it already pushed up isn't going anywhere. The surge risk remains the same.

- Get a NOAA Weather Radio: Internet and cell towers are the first things to go. You need a battery-operated or hand-crank radio to get real-time updates from the National Weather Service.

The Saffir Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is a great starting point, but it's just the cover of the book. To stay safe, you’ve gotta read the whole thing.

Next Steps for Your Safety:

Check your local flood zone maps today—even if you're miles from the beach—and verify your "evacuation zone" through your county's emergency management website. Wind is a threat, but water is the reason you leave.