History has a way of being messy. Usually, when we talk about the Sabra and Shatila massacre, people retreat into their ideological corners almost immediately. It’s one of those events that feels frozen in 1982, yet it still dictates the emotional temperature of Middle Eastern politics today.

If you look at the raw facts, they are brutal. Between September 16 and September 18, 1982, a Lebanese Christian militia known as the Phalange entered two Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut. By the time they left, hundreds—some estimates say thousands—of civilians were dead. But the "why" and the "how" are where things get complicated. People often forget that this wasn't just a random act of violence; it was the climax of a chaotic civil war and a foreign invasion that had already torn Lebanon into pieces.

The atmosphere in Beirut that September was thick. It was heavy. Bashir Gemayel, the newly elected president and leader of the Maronite Christians, had just been assassinated in a massive bomb blast. His followers were out for blood. They wanted revenge. And the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), who had surrounded the camps, let them in.

The Three Days in September

The timeline matters. Honestly, it's the only way to understand how things spiraled so quickly. On September 15, the day after Gemayel’s death, the IDF moved into West Beirut. Their stated goal? To root out remaining PLO fighters who they claimed were still hiding in the refugee camps.

By Thursday, September 16, around 6:00 PM, approximately 150 Phalangists entered the Sabra and Shatila camps.

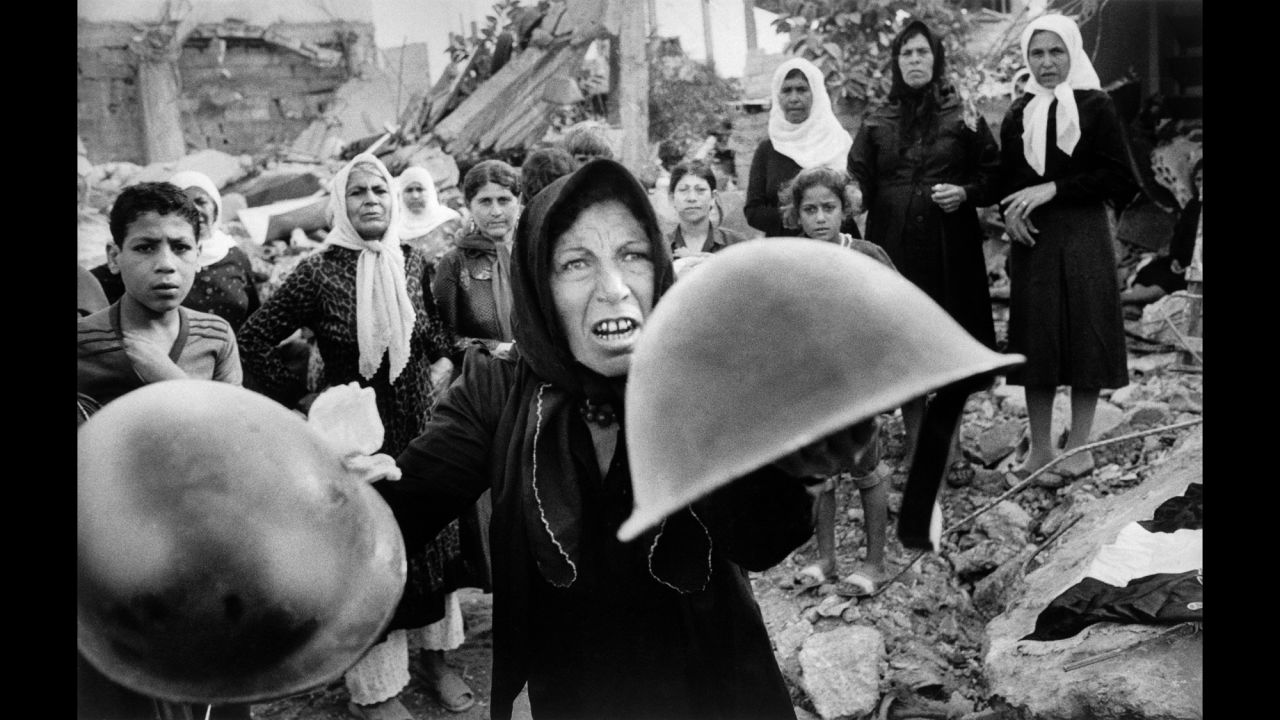

For the next 36 to 48 hours, the world outside had no idea what was happening. Inside, it was a nightmare. The militia didn't just look for combatants. They targeted everyone. Elderly men, women, children—no one was spared. We know this because of the harrowing accounts from survivors and the journalists who rushed in the moment the militia retreated. Janet Lee Stevens, an American journalist, was one of the first on the scene. Her descriptions of the bodies found in the streets are still some of the most visceral records we have of the carnage.

Why the Kahan Commission Changed Everything

You can't talk about the Sabra and Shatila massacre without talking about the Kahan Commission. This was Israel’s own internal investigation, established after 400,000 Israelis protested in Tel Aviv—a massive number for such a small country. They were horrified. They wanted answers.

💡 You might also like: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

The commission didn't find that Israeli soldiers pulled the triggers. It did, however, find that Israel bore "indirect responsibility." The report was blunt. It stated that Ariel Sharon, the Defense Minister at the time, bore "personal responsibility" for ignoring the danger of bloodshed when he allowed the Phalangists into the camps.

Sharon was eventually forced to resign his post. It’s a detail people often skip: the fact that the most damning critique of the military’s role came from within Israel itself. This wasn't just "enemy propaganda." It was a formal legal finding by the Israeli Supreme Court Justice Yitzhak Kahan.

The Numbers Game

How many people actually died? This is where the historical record gets blurry, and honestly, we might never have a perfect number. The Lebanese Red Cross claimed around 460 bodies were recovered. However, the Palestinian Red Crescent put the number closer to 2,000.

Why the massive gap?

- Mass graves: Many bodies were buried in haste by the militia before they left.

- Disappearances: Hundreds of people were marched out of the camps and never seen again.

- Documentation: In the chaos of 1982 Lebanon, record-keeping wasn't exactly a priority.

Independent researchers, like the late British journalist Robert Fisk, who was physically there as the bodies were being discovered, argued that the scale of the killing suggested the higher end of those estimates was much more likely. Fisk's reporting for The Times remains some of the most cited evidence of the sheer brutality of the scene.

The Role of the International Community

There is a lot of blame to go around, and some of it lands squarely on the shoulders of the United States. Just weeks before the massacre, the U.S. had brokered a deal to evacuate the PLO from Beirut. Part of that deal involved a written guarantee from the U.S. that the civilians left behind in the camps would be protected.

📖 Related: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

The Multinational Force (MNF), which included U.S. Marines, was supposed to stay and ensure safety. Instead, they left early.

When the IDF moved into West Beirut, the U.S. government—specifically special envoy Morris Draper—sent cables expressing concern, but the diplomatic pressure wasn't fast enough to stop the militia. The failure of the international community to uphold its promise to protect the refugees is a recurring theme in Palestinian history. It’s why there is such deep-seated skepticism regarding "international guarantees" today.

Misconceptions You Should Probably Forget

A common myth is that the massacre was a planned joint operation between Israel and the Phalangists. The reality is more nuanced. While the IDF provided flares to light up the night sky over the camps and controlled the perimeter, there is no verified evidence that Israeli soldiers entered the camps to participate in the killings.

However, the "indirect responsibility" mentioned earlier is heavy. If you provide the light, the logistical support, and the entry point for a group that has openly talked about revenge, you can't really act surprised when a massacre happens. That was the core logic of the Kahan Commission.

Another misconception? That this was only about Palestinians. It’s easy to forget that the camps also housed Lebanese Shiites and other poor residents of Beirut. The violence was sectarian, yes, but it was also fueled by a decade of internal Lebanese grudges that had nothing to do with the Arab-Israeli conflict and everything to do with local power struggles.

The Long-Term Impact on Lebanon

The Sabra and Shatila massacre didn't just end with the burials. It fundamentally changed the trajectory of the Lebanese Civil War. It radicalized a generation. It also contributed to the rise of Hezbollah. As the vacuum of power in Southern Lebanon and Beirut grew, and as faith in international intervention withered, more militant groups began to fill the void.

👉 See also: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

For the survivors, the trauma is multi-generational. Walk through Shatila today—it's still a cramped, impoverished neighborhood—and you'll see the posters of the "martyrs." The memory isn't "history" there. It’s the present.

Lessons That Still Apply

Looking back at the Sabra and Shatila massacre, it’s clear that military objectives often blind leaders to humanitarian realities. You can't outsource security to a vengeful militia and expect a clean outcome.

If you’re trying to understand the modern Middle East, you have to look at these inflection points. You have to look at the moments where the rules of war were ignored. The massacre remains a touchstone for international law, frequently cited in discussions about the "duty to protect" and the legal definition of complicity.

Moving Forward: What to Do With This Information

Understanding this event requires more than reading a single article. To get a full picture of the complexity of 1982, there are specific steps you should take to verify these facts and see the nuances for yourself.

- Read the Kahan Commission Report: You can find the executive summary online. It’s a fascinating look at how a state holds its own military and political leaders accountable during a time of war.

- Watch "Waltz with Bashir": This is an Israeli animated documentary that deals specifically with the memories of soldiers who were in Beirut at the time. It’s not a traditional history, but it captures the psychological weight of the event better than almost anything else.

- Check the Red Cross Archives: For those interested in the raw data of the casualties, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has extensive records on the humanitarian response in Beirut during the fall of 1982.

- Examine the MacBride Commission: This was an independent international commission headed by Sean MacBride. Their report, Israel in Lebanon, offers a much harsher legal critique than the Kahan Commission and provides a necessary counter-perspective on the legalities of the invasion.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre serves as a grim reminder of what happens when civilian safety is treated as a secondary concern to political maneuvering. It’s a dark chapter, but ignoring the details only makes it harder to understand the cycles of violence that continue to plague the region today. Historical literacy isn't about picking a side; it's about acknowledging the full, uncomfortable scope of what human beings are capable of when they stop seeing their neighbors as people.