When you think about the 1917 Russian Revolution, you probably imagine cold streets, starving workers, and the dramatic storming of the Winter Palace. But honestly? The real battle wasn't just fought with Mosin-Nagant rifles. It was fought with ink, paper, and some of the most aggressive graphic design the world had ever seen. Russian revolution propaganda didn't just support a political shift; it fundamentally redesigned how humans process political messaging. The Bolsheviks realized something the Romanovs didn't: if you can control the image, you can control the reality of the peasant in a village five hundred miles away from Petrograd.

History books often make it sound like the Bolsheviks just walked into power because the Tsar was incompetent. While Nicholas II certainly wasn't winning any "Ruler of the Year" awards, the transition of power was fueled by a massive, coordinated psychological campaign. This wasn't just about "Peace, Land, and Bread." It was about creating a visual language that an illiterate population could understand at a glance.

The Visual Language of the Red Terror

Imagine you're a Russian peasant in 1918. You can’t read. You’ve never been more than twenty miles from your farm. Suddenly, a train pulls into your local station—not a normal train, but an "Agit-train" covered in bright, screaming colors and massive paintings of monsters and heroes.

This was the genius of the Bolshevik approach. They didn't wait for people to find the news; they brought the news to the people in a format that didn't require a degree. The Agit-prop (agitation and propaganda) trains were essentially mobile cinemas and printing presses. They carried films, posters, and speakers to the deepest corners of the Russian countryside. It was the 20th-century version of a viral social media campaign, but with steam engines.

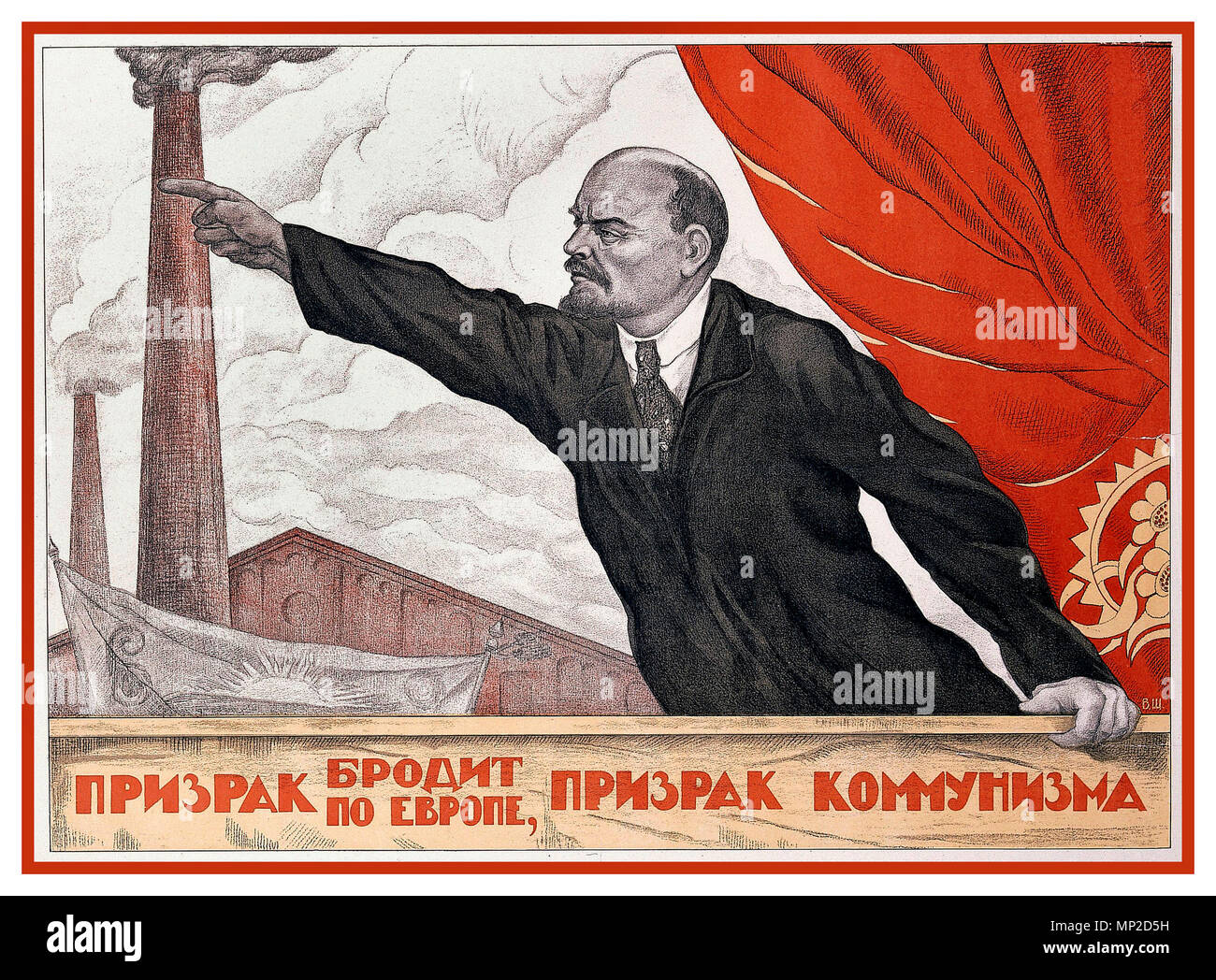

The imagery was brutal. It had to be. In many posters, Leon Trotsky or Vladimir Lenin were depicted as giant figures sweeping the "filth" off the earth. This wasn't subtle. One of the most famous pieces of Russian revolution propaganda is El Lissitzky's "Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge." It's an abstract geometric painting—a red triangle piercing a white circle. It looks like modern art because it was modern art. The Bolsheviks recruited the avant-garde. They took the weirdest, most experimental artists of the era, like Malevich and Rodchenko, and told them to make the revolution look like the future.

Why the "Whites" Failed the Vibe Check

The anti-Bolshevik "White Army" had plenty of resources. They had international backing. They had experienced generals. What they didn't have was a coherent brand. While the Reds were unified under a single, violent, but clear vision, the Whites were a mess of monarchists, liberals, and foreign interests.

📖 Related: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

White Army posters often looked like old-fashioned religious icons or stiff military recruitment flyers. They were boring. They felt like the past. The Bolsheviks, meanwhile, were using bold typography and primary colors. They made the revolution look inevitable. If you're a starving worker, are you going to join the guy who wants to bring back the system that starved you, or the guy who looks like a superhero in a poster? Exactly.

The Cult of Personality Before it Was a Cliche

We talk about "cults of personality" like they’re a standard part of politics now. Back then? This was cutting-edge stuff. Lenin actually hated the idea of being idolized—or at least he said he did—but he understood its utility.

After a failed assassination attempt by Fanny Kaplan in 1918, the propaganda machine went into overdrive. Suddenly, Lenin wasn't just a politician; he was a martyr-in-waiting, a saint of the secular world. The posters shifted. They started showing him with a kind of halo-effect, standing above the masses, pointing toward a glowing horizon.

This used the existing religious "muscle memory" of the Russian people. For centuries, they had looked at icons of Orthodox saints. The Bolsheviks just swapped out Saint Nicholas for Vladimir Lenin. They kept the format but changed the god. It was a brilliant, cynical pivot. They even used "ROSTA Windows," which were essentially giant comic strips pasted in empty shop windows. People would gather around to see the latest installment of the revolution's progress. It was addictive. It was communal.

The Agit-Train: A High-Tech Invasion

Let's talk about the tech. 1917-1921 saw the birth of the "Agit-train." These were literal trains, painted from top to bottom with revolutionary scenes. They didn't just carry posters; they carried film projectors.

👉 See also: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

Most people in rural Russia had never seen a "moving picture." When a Bolshevik train arrived and projected a movie onto a sheet hung off the side of a boxcar, it felt like magic. If the movie told you that the Bolsheviks were the only ones who could save you from the "Capitalist Vampires," you tended to believe it. This wasn't just information; it was a sensory assault.

The trains also had onboard printing presses. They could roll into a town, hear the local rumors, and print a custom newspaper addressing those specific rumors by the next morning. That kind of speed was unheard of. It made the Soviet government feel omnipresent and hyper-efficient, even when the reality was total chaos and famine.

The Women of the Revolution (On Paper)

Propaganda targeted women specifically, which was a huge shift. Posters depicted "The New Soviet Woman"—someone who was no longer a "slave to the kitchen" but a productive member of the factory floor. They promised communal nurseries and laundries.

Of course, the reality didn't always match the glossy poster. While the propaganda showed women standing shoulder-to-shoulder with men, the domestic burden rarely actually lifted. But as a recruitment tool? It was incredibly effective. It gave a voice to a demographic that the Tsar had essentially ignored for three hundred years.

The Dark Side: Dehumanization as a Tool

It wasn't all bright colors and "New Worlds." A massive part of Russian revolution propaganda was dedicated to making the "enemy" look like something other than human.

✨ Don't miss: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

The "Burzhui" (the bourgeoisie) were almost always drawn as fat, pig-like men in top hats, literally sitting on the backs of workers. Priests were depicted as greedy hypocrites hiding bags of gold. By turning political opponents into caricatures, the Bolsheviks made the subsequent violence of the Red Terror feel justifiable. It's much easier to support the "liquidation of a class" when you've been conditioned to see that class as literal parasites.

The language used was just as sharp as the drawings. They used words like "bloodsuckers," "spiders," and "scum." It was visceral. It was meant to trigger an emotional, gut-level response of disgust.

How the Message Changed When the War Was Won

Once the Civil War ended and the Bolsheviks were firmly in charge, the propaganda didn't stop—it just pivoted. It moved from "destroy the old world" to "build the new one." This is where we see the rise of Socialist Realism.

The posters got cleaner. The art became less experimental and more "realistic" (though a very idealized version of reality). This is the era of the muscular factory worker looking heroically into the distance. The chaos of the 1917 avant-garde was replaced by a rigid, state-controlled aesthetic. The revolution had become the establishment.

Real-World Lessons from 1917

What can we actually learn from this? Looking back, the success of the Bolsheviks proves that in times of crisis, the side with the clearest, most accessible narrative wins. It doesn't matter if your policy papers are 400 pages long if the other guy has a poster that makes people feel something.

- Simplicity is King: The "Peace, Land, Bread" slogan is legendary because it addressed the three things people actually cared about. No jargon. No complex economic theories.

- Visual Consistency: The use of the color red wasn't accidental. It was a brand. It was bold, it was energetic, and it was easy to identify.

- Platform Matters: Using trains and films in a pre-digital age was the equivalent of mastering the algorithm today. They met the audience where they were.

Take Action: Analyzing the "New" Propaganda

We live in a world that is just as saturated with messaging as revolutionary Russia, though it’s much more subtle now. To avoid being "Agit-propped" yourself, you have to look at the mechanics of the media you consume.

- Deconstruct the Image: Next time you see a political ad or a viral infographic, ask: Who is the hero? Who is the "parasite"? Is the imagery trying to make me think, or is it trying to make me feel disgusted?

- Check the Source Speed: One of the Bolsheviks' biggest strengths was being first to the story. In the modern world, "breaking news" is often wrong. Don't let the speed of the delivery convince you of its accuracy.

- Look for the "Red Wedge": Identify the "simple solutions" being offered for complex problems. If a political message can be boiled down to a single geometric shape or a three-word slogan, it’s probably omitting about 90% of the truth.

The history of Russian revolution propaganda isn't just a museum piece. It's a blueprint for how to sway a nation. By understanding how the Bolsheviks used art and technology to seize power, we get a much clearer view of how modern influence campaigns work today. History doesn't repeat, but the techniques of persuasion definitely do.