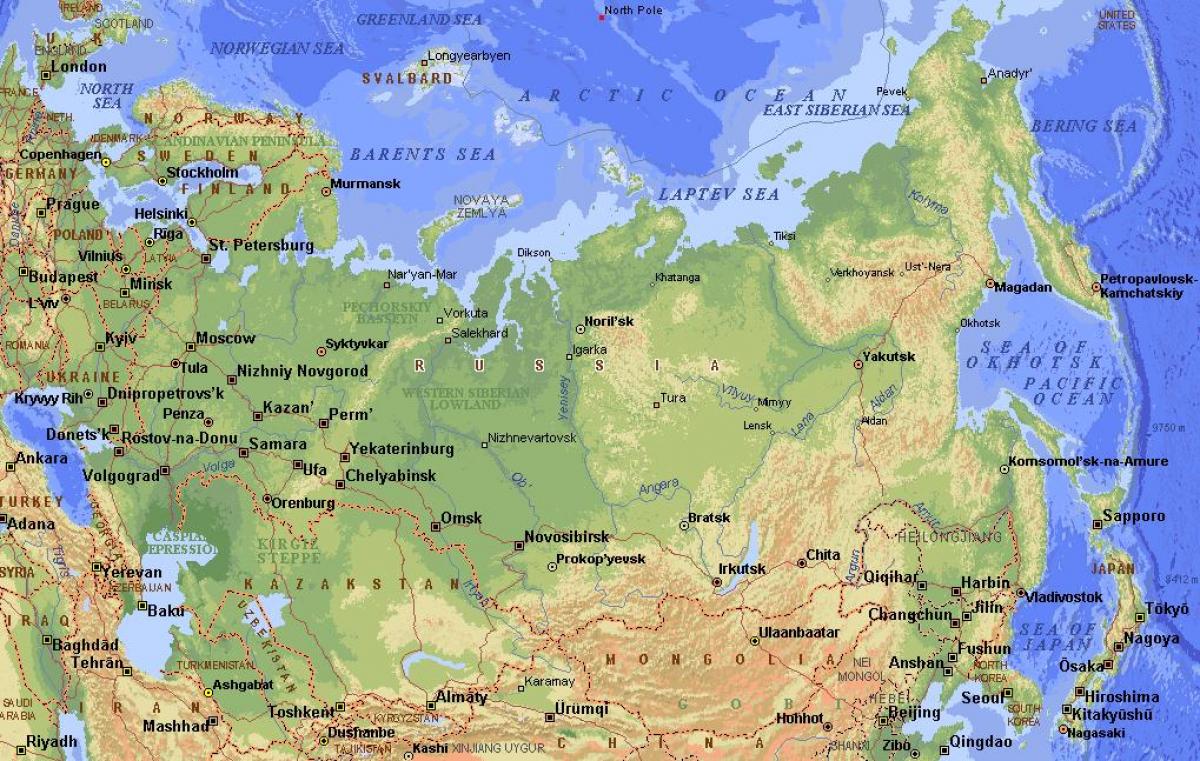

Russia is just too big. Seriously. When you look at a russia physical features map, your brain kind of struggles to process the scale because it covers eleven time zones. That is insane. If you started a Zoom call in Kaliningrad at breakfast, your colleagues in Kamchatka would be getting ready for bed. Most maps make it look like one giant, frozen block of taiga, but that’s a massive oversimplification that ignores the actual texture of the land.

You’ve probably seen the standard green-and-brown topographical layouts. They show the Ural Mountains slicing down the middle like a jagged spine. But honestly? The Urals aren't even that tall. They’re old, weathered, and more of a symbolic fence between Europe and Asia than a physical wall. The real drama happens much further east and south.

The Great European Plain isn't as flat as you think

Most of Russia’s population huddles in the west. This is the Russian Plain. On any russia physical features map, this area looks like a huge, boring green smudge. It’s the northern part of the Great European Plain. While it is "flat" compared to the Himalayas, it’s actually full of rolling Valdai Hills and river basins that have dictated Russian history for a thousand years.

The Volga River starts here. It’s the longest river in Europe, but it doesn't even reach an ocean—it dumps into the Caspian Sea. Think about that. The most important waterway in the country is basically a dead end. This region is the breadbasket, but the soil gets progressively more finicky as you move north toward the Arctic Circle.

Breaking down the Ural divide

People obsess over the Urals. Geographers like to point at them and say, "There, that’s where Europe ends." But if you actually stood on the slopes of Narodnaya, the highest peak at about 1,895 meters, you wouldn't feel like you're on top of the world. You’d feel like you’re on a very old, very tired pile of rocks.

They are incredibly rich in minerals, though. Iron, copper, gold—the Soviet industrial machine was basically built out of the guts of these mountains. On a physical map, they look like a barrier, but historically, they’ve been more of a bridge.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

The West Siberian Plain: A giant, soggy sponge

Cross the Urals and everything changes. You hit the West Siberian Plain. It is arguably the flattest place on the planet. We are talking about a territory the size of the United States east of the Mississippi where the elevation barely changes.

Because it’s so flat, the water has nowhere to go.

The Ob and Irtysh rivers just sort of wander around, creating some of the largest swamps in the world. The Vasyugan Swamp is the big one. It’s bigger than Switzerland. If you're looking at a russia physical features map, this is the area that looks like a vast, featureless lowland. In reality, it’s a treacherous landscape of peat bogs and permafrost that makes building anything—roads, pipelines, cities—an absolute nightmare.

- The northern part is mossy tundra.

- The middle is dense "dark" taiga (pine, fir, spruce).

- The south turns into the fertile steppe.

It’s not just "snow." It’s a complex hydrological system that stores massive amounts of carbon. If those bogs melt completely, we’re all in trouble.

Central and Eastern Siberia: Where the real mountains hide

Once you cross the Yenisei River, the ground starts to heave upward. This is the Central Siberian Plateau. It’s rugged. It’s ancient. It’s mostly volcanic rock known as the Siberian Traps. About 250 million years ago, this whole area erupted in one of the biggest volcanic events in Earth's history. It nearly wiped out all life on the planet.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

Today, it’s a high, dissected plateau. It’s beautiful but incredibly harsh.

Further east, you hit the truly wild stuff. The Chersky Range, the Verkhoyansk Range, and the Stanovoy Highlands. These aren't the gentle hills of the west. These are sharp, jagged, and cold. This is where you find Oymyakon, the coldest inhabited place on Earth. A russia physical features map shows this area as a chaotic mess of brown and purple lines, indicating high elevation.

Lake Baikal is a literal hole in the earth

You can't talk about Russian geography without Baikal. It’s not just a lake. It’s a rift valley. The Earth is literally pulling apart here. It holds 20% of the world’s unfrozen freshwater. It’s so deep (over 1,600 meters) that you could submerge the Burj Khalifa in it and still have nearly a kilometer of water above it.

The water is so clear you can see forty meters down. It has its own species of seals. Freshwater seals! Evolution went wild in this isolated pocket of Siberia.

The Ring of Fire on the Kamchatka Peninsula

If you look at the far right of your russia physical features map, you’ll see a tail hanging down into the Pacific. That’s Kamchatka. It is one of the most volcanically active places on the globe.

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

There are over 160 volcanoes here. 29 of them are still very much alive. Klyuchevskaya Sopka is the "big boss"—a perfect cone that shoots ash into the stratosphere on a regular basis. This isn't the Siberia of popular imagination; it’s a land of geysers, acid lakes, and giant brown bears. It’s more like Alaska or Iceland than Moscow.

- Klyuchevskaya Sopka: The highest active volcano in Eurasia.

- Valley of Geysers: The second-largest concentration of geysers in the world.

- Kronotsky Nature Reserve: Often called the "Land of Fire and Ice."

The Caucasus: Russia’s rooftop

Down in the southwest, sandwiched between the Black and Caspian Seas, are the Caucasus Mountains. This is where Russia actually gets tall. Mount Elbrus is here. At 5,642 meters, it is the highest point in Russia and, depending on how you draw the border, the highest point in Europe.

The climate here is totally different. You go from alpine glaciers to subtropical tea plantations on the Black Sea coast in just a few hours. A physical map shows this as a narrow, violent upward thrust of the crust. It’s a tectonic collision zone where the Arabian plate is smashing into the Eurasian plate.

What this means for anyone actually looking at the map

When you study a russia physical features map, stop looking for a uniform country. It doesn't exist. Russia is a collection of impossible extremes.

The "Russian Winter" everyone talks about is actually several different types of cold. In St. Petersburg, it’s a damp, bone-chilling humidity. In Yakutsk, it’s a dry, "your-eyelashes-snap-off" kind of cold. The geography dictates the culture, the economy, and even the psychology of the people living there.

Practical steps for exploring Russian geography further:

- Check out Yandex Maps: It often has better topographical detail for Russian territories than Google Maps. Use the "Satellite" and "Hybrid" layers to see the actual vegetation changes.

- Study the Drainage Basins: Look at how the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena rivers all flow north. This "Northward Flow" is why the interior of the country stays so swampy—the mouths of the rivers stay frozen while the southern parts melt, creating massive backups.

- Investigate the Permafrost Line: Use a specialized map to see where the "continuous permafrost" begins. It covers nearly 65% of Russia’s landmass. This is the single most important physical feature that isn't always visible on a standard color-coded map.

- Look at the "Big Three" Altitudes: Compare the depths of the Caspian Depression (below sea level), the heights of the Caucasus (5,000m+), and the flatlands of the West Siberian Plain to understand the vertical diversity.

The reality of Russia's physical landscape is that it’s mostly empty of people but full of geographical obstacles. It’s a map of constraints—mountains that are too old to cross easily, plains that are too wet to farm, and an Arctic coastline that is frozen for most of the year. Understanding these features is the only way to understand why the country functions the way it does.