Honestly, if you grew up in a house with a well-stocked bookshelf, you’ve probably met Frances. She’s a badger. But she’s not really a badger—she’s every four-year-old who ever lived. She’s stubborn, she’s a lyrical genius of the playground, and she has a very specific set of demands regarding jam. Russell Hoban Frances books aren’t just "classics" in that dusty, homework-assignment way. They are survival manuals for parents and mirrors for kids.

I was recently flipping through a tattered copy of Bread and Jam for Frances and it hit me. These books are weirdly honest. They don’t lecture. They don't have that "and the moral of the story is" vibe that makes modern picture books feel like a corporate HR seminar. Instead, they just... exist in the messy reality of childhood.

The Badger Who Refused to Eat Her Eggs

The series kicked off in 1960 with Bedtime for Frances. Interestingly, it’s the only one not illustrated by Lillian Hoban. Garth Williams did the art for the first one—the same guy who drew Charlotte’s Web—and he made Frances look a bit more like a traditional woodland creature. By the time Lillian took over for the sequels, Frances became the fuzzy, slightly bedraggled badger we all recognize.

The vibe of these books is basically "toddler logic taken to the extreme." Take Bread and Jam for Frances. It’s the ultimate picky eater manifesto. Frances decides she only likes bread and jam because, as she puts it, "When I have bread and jam I always know what I am getting, and I am always pleased."

It’s a mood.

Most authors would have the parents force her to eat spinach. Not Russell Hoban. Frances's parents are the kings of reverse psychology. They just... stop giving her anything else. They give her bread and jam for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks. They give it to her while they eat veal cutlets and spaghetti. Eventually, Frances cries because she wants a soft-boiled egg. It’s a brilliant, quiet victory for parents everywhere.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With the Russell Hoban Frances Books

What really makes the Russell Hoban Frances books stick in your brain isn't the plots. It's the songs. Frances is constantly making up little rhymes to process her feelings. When she’s mad at her friend Albert in Best Friends for Frances, or jealous of her sister in A Birthday for Frances, she sings.

There’s something so authentic about those lyrics. They aren't "professional" poems. They are clunky and rhythmic and sorta perfect.

The Realism of "Thelma"

If you want to talk about the complexity of the series, you have to talk about A Bargain for Frances. This is the one where Frances deals with Thelma. We all knew a Thelma. Thelma is the "friend" who manipulates you into trading your brand-new china tea set for a plastic one with "sugar cracks."

👉 See also: July 31 2025 Daily Horoscope: Why Everyone Is Feeling That Weird Tension

It’s a brutal look at childhood politics.

Frances doesn't just "be the bigger person." She gets her revenge. She out-manipulates Thelma to get her tea set back (and a little extra). It’s not "nice," but it’s real. Children’s literature often tries to pretend kids are little angels who just need a hug to solve a dispute. Hoban knew better. He knew that sometimes you have to play the game to win your tea set back.

The Secret Sauce: Russell and Lillian’s Partnership

The history behind these books is kinda bittersweet. Russell Hoban wrote them, and his wife Lillian illustrated most of them. They had four kids, and you can tell. The dialogue between the parents in the books—Father reading the newspaper, Mother calmly navigating a crisis—feels like it was transcribed from a real 1960s kitchen.

They eventually divorced in 1975, which is a bit of a gut punch for fans who grew up on their cozy collaborations. But the work they left behind is bulletproof.

📖 Related: Plants for Flower Boxes: Why Your Window Display Usually Dies and How to Fix It

- Bedtime for Frances (1960): The one where she sees giants in the curtains.

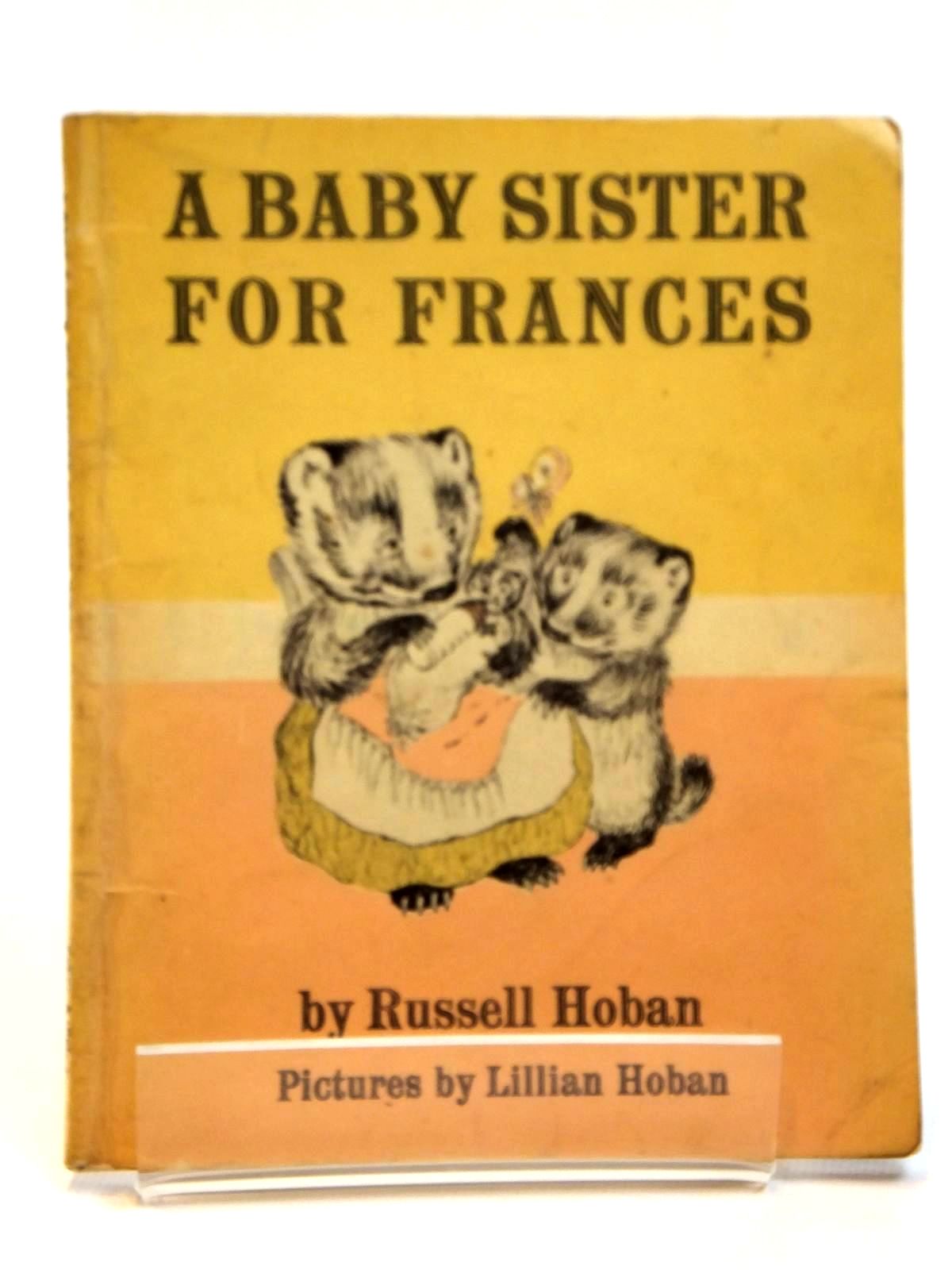

- A Baby Sister for Frances (1964): The one where she "runs away" to under the dining room table.

- Bread and Jam for Frances (1964): The picky eater's Bible.

- A Birthday for Frances (1968): A deep dive into the agony of giving a gift you want to keep.

- Best Friends for Frances (1969): Dealing with "no girls allowed" shenanigans.

- A Bargain for Frances (1970): The tea set heist.

Is Frances "Problematic" in 2026?

You'll occasionally see people on the internet—usually on Goodreads or Reddit—getting heated about these books. Some people think the parents are too strict. There's a mention of a "spanking" in the first book that definitely feels like a relic of 1960. Others argue Bread and Jam is fat-phobic because it focuses on food and body size, though that feels like a stretch when the book is really about the monotony of a limited diet.

Most modern readers just see a family trying to get through the day without a meltdown. The parents are patient but they have limits. That makes them relatable, not outdated.

How to Introduce Frances to a New Generation

If you’re looking to get these for a kid today, don’t buy a "best of" collection. Go for the individual paperbacks. There’s something about the size of the original books that fits perfectly in a small hand.

Start with Bread and Jam. It’s the most accessible. Then move to A Bargain for Frances once they’re old enough to understand what a "backstabber" is.

Watch for the details. Lillian Hoban’s illustrations are full of little things—the way the badger family dresses, the specific snacks they pack for picnics (hard-boiled eggs with a little cardboard shaker of salt!).

Read the songs aloud. Don't try to be a good singer. Just chant them the way a kid would.

The Russell Hoban Frances books work because they respect children. They don't talk down to them. They acknowledge that being small is often frustrating, unfair, and confusing. And usually, the best way to handle it is with a good song and a jam sandwich.

To get the most out of these classics, try tracking down the original 1960s or 70s editions at a used bookstore. The color saturation in the newer reprints can sometimes feel a bit "plastic" compared to the muted, cozy tones of the vintage copies. If you’re reading A Baby Sister for Frances with a child, use it as a low-pressure way to talk about the "under the table" feelings they might be having themselves. It works better than any parenting book I’ve ever found.