Eleven minutes. That is a massive amount of time to ask from a listener in the age of the radio edit. But back in 1981, Rush didn't really care about your attention span. They were busy painting a sonic portrait of two cities that felt like they were vibrating on different frequencies. Honestly, if you listen to Moving Pictures today, "The Camera Eye" feels like the heavy anchor of the B-side. It’s the last of its kind.

Neil Peart was reading a lot of John Dos Passos at the time. You can hear it. The song isn't just a track; it's a literal lens. It starts with the ambient noise of a city street—honking horns, muffled voices—before Geddy Lee’s synthesizers begin to swell like a sunrise over a skyline. It’s patient. It’s arguably the most "prog" thing they ever did right before they decided to stop being a "prog" band in the traditional sense.

Why The Camera Eye Was a Turning Point

For a lot of fans, this track represents the end of an era. Think about it. Before this, you had the twenty-minute side-long odysseys like "2112" or "Hemispheres." By the time they got to Le Studio in Quebec to record Moving Pictures, the band was tightening up. They were becoming masters of the four-minute masterpiece like "Limelight" or "Tom Sawyer." Yet, "The Camera Eye" remained. It was the final gasp of the long-form narrative.

Alex Lifeson’s guitar work here is underrated. People always talk about his solos in "Working Man" or "La Villa Strangiato," but his textures in the New York and London sections of this song are basically a masterclass in atmosphere. He uses a lot of open strings and chorused delays to make the guitar feel as wide as a city block. It isn't just shredding; it's architecture.

The song is split. It’s a tale of two cities. New York is frantic, busy, and "grim-faced." London is gray, historical, and "shrouded in the memories of the night." Peart’s lyrics capture that specific 1980s urban decay and energy. He wasn't just writing fantasy stories about wizards anymore. He was looking out the window of a tour bus and writing down what he saw. It was real. It was gritty.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Technical Grind of the Eleven-Minute Mark

Recording this wasn't easy. Producer Terry Brown has mentioned in various interviews over the years that the band was moving toward a more streamlined sound. "The Camera Eye" was the outlier. It required a level of precision that was exhausting. You’ve got these shifting time signatures that feel natural but are actually nightmare-inducing for a drummer.

Most people don't realize how much the Oberheim OB-X synthesizer dominates the feel of this track. It provides that thick, lush bed that allows the bass and drums to dance. Geddy Lee was playing bass pedals, keys, and singing all at once. It’s a lot. If you watch live footage from that era, the sheer coordination required to pull this off is staggering. They were a three-piece band sounding like a thirty-piece orchestra.

The Mystery of the Missing Live Staple

For decades, "The Camera Eye" was the "Holy Grail" for Rush fans. Why didn't they play it? Between 1983 and 2010, it completely vanished from their setlists. It became a meme before memes existed. Fans would hold up signs at every show begging for it.

Geddy Lee was always pretty honest about why they dropped it. He felt it was a bit too long and perhaps didn't translate the "energy" required for a modern rock show. He thought it was a bit "plodding." Can you believe that? The fans disagreed. Violently.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

It took the Time Machine Tour in 2010-2011 for the band to finally give in. They played the entire Moving Pictures album start to finish. When those first synthesizer chords of "The Camera Eye" hit, the collective roar of the crowd was enough to shake the rafters. It was a validation. It proved that the song hadn't aged a day. It still felt cinematic. It still felt relevant.

Breaking Down the New York vs. London Contrast

The lyrics aren't just descriptions; they are social commentaries. In the New York section, Peart writes about "The focus sharp, the image clear." It’s about the frantic pace of American capitalism. The music matches this with a driving, relentless rhythm. It feels like walking through Times Square when it was still dangerous and exciting.

Then the mood shifts.

When we get to London, the music breathes a bit more. "The quality of light / The strength of night." It’s more contemplative. It’s slower. It’s British. This contrast is what makes the eleven minutes fly by. If it were just one long jam, it would get boring. But because it’s a diptych—a two-part painting—it keeps the listener engaged. You’re traveling. You don't even need a passport.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

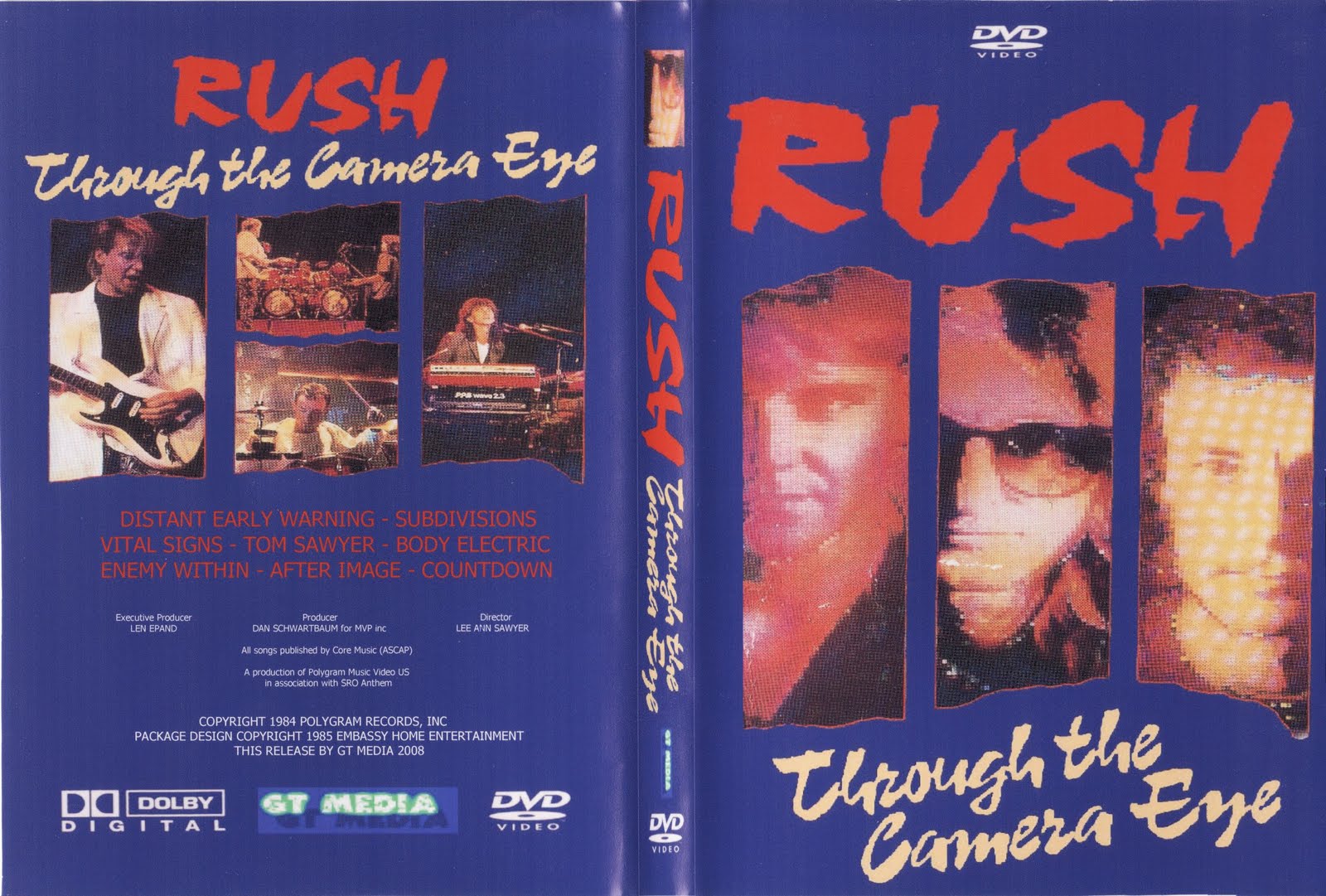

The Legacy of the Last Great Epic

After Moving Pictures, Rush went "New Wave." They cut their hair. They bought more synths. They started writing shorter songs like "Subdivisions" and "New World Man." They never wrote another eleven-minute multi-part epic again. In that sense, "The Camera Eye" is the tombstone for 1970s progressive rock.

It’s the bridge. One foot is in the past (the long-form exploration) and one foot is in the future (the polished, rhythmic precision).

Critics at the time were sometimes dismissive. Some thought it was filler. Retrospectively, that’s insane. It’s the heartbeat of the album. Without it, Moving Pictures is just a collection of great singles. With it, the album is a magnum opus. It gives the record scale. It gives it gravitas.

Actionable Listening Guide for the Modern Ear

If you really want to appreciate what’s happening in "The Camera Eye," you can't just play it through phone speakers. You’ll miss the nuance. You need to do this properly:

- Get a pair of open-back headphones. The stereo imaging on this track is legendary. There are sounds bouncing from left to right that define the "city" atmosphere.

- Focus on the 6:30 mark. This is the transition point. Listen to how Neil Peart uses his ride cymbal to shift the "energy" from the New York hustle to the London fog. It’s subtle but brilliant.

- Watch the Time Machine Tour version. Compare the 1981 studio recording to the 2011 live version. You can see the joy on Alex Lifeson’s face when he finally gets to play that soaring solo again. It’s pure catharsis.

- Read the lyrics while listening. Don't just let the words wash over you. Look at the imagery. See the "grim-faced and silent" people. It turns the song into a short film in your head.

"The Camera Eye" remains a testament to what happens when three virtuosos decide to take their time. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the long way around is the only way worth taking. It isn't just a song on a classic rock album; it's a piece of musical geography that mapped the transition from the experimental seventies to the digital eighties. It stands alone.