You probably haven't thought about rubella in years. Maybe never. For most of us born after the mid-1960s, it’s just a line item on a yellowing vaccination card, tucked away between mumps and measles. But rubella cases in US history tell a story of a massive public health victory that is, quite frankly, a bit more fragile than we’d like to admit.

It’s a weird virus.

In kids, it’s basically a nothing-burger. A light fever, a pinkish rash that starts on the face and migrates down, maybe some swollen glands behind the ears. You feel crummy for three days—hence the nickname "three-day measles"—and then you're fine. But the math changes completely if a pregnant woman catches it. That is where the "mild" virus becomes a nightmare.

What actually happened to rubella cases in US history?

We used to have hundreds of thousands of cases. In 1964 and 1965, the United States got hit by a massive epidemic. We're talking 12.5 million rubella cases in just a couple of years. The fallout was devastating: 11,000 miscarriages or therapeutic abortions and 20,000 babies born with Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS).

Those kids faced a lifetime of challenges. Deafness, cataracts, heart defects, and intellectual disabilities. It was a national crisis.

The turning point came in 1969 when the first vaccines were licensed. We went from tens of thousands of cases annually to... nothing. Well, almost nothing. By 2004, experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially declared that rubella was eliminated from the United States. That doesn't mean the virus is extinct, like smallpox. It just means it's no longer "endemic," or circulating constantly within our borders.

The "Elimination" Trap

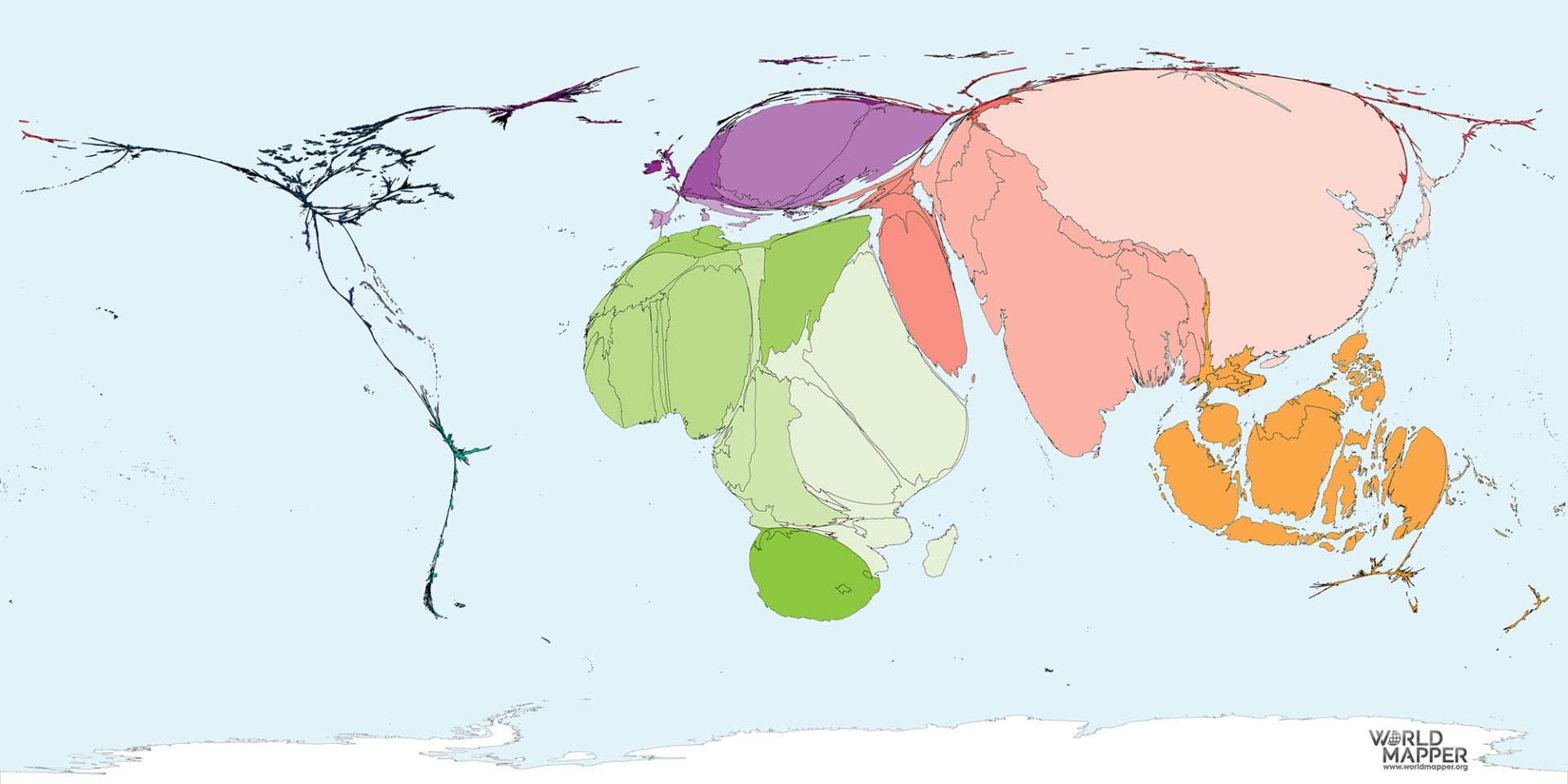

Don't let the word "elimination" fool you into thinking the risk is zero. We still see rubella cases in US data every single year. Usually, it’s less than 10 people. These are almost always "imported" cases. Someone travels to a country where rubella is still common—parts of Africa, the Middle East, or Southeast Asia—catches it, and brings it back in their bloodstream.

🔗 Read more: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

The reason it doesn't spark a massive wildfire of an outbreak is "herd immunity." Because most of us are vaccinated with the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) shot, the virus hits a dead end. It can’t find enough susceptible hosts to keep jumping.

But what happens if that wall starts to crumble?

Why the numbers could shift

Honestly, the biggest threat to our rubella-free status isn't the virus itself; it's complacency. In 2026, we're seeing more parents questioning routine vaccinations. If the percentage of vaccinated kids in a specific community—say, a tight-knit religious group or a private school—drops below a certain threshold, the "herd" is no longer protected.

Take the 2013 outbreak in a communal setting in Texas, or the more recent measles spikes we've seen in places like Florida or the Pacific Northwest. While those were measles, the principle is the same. Rubella is just as contagious. If an unvaccinated traveler returns to a community with low MMR coverage, we could easily see dozens of rubella cases in US neighborhoods that haven't seen the rash in decades.

Who is actually at risk?

- Unvaccinated travelers: This is the big one. If you’re heading to a region where the vaccine isn't standard, you're a target.

- Health care workers: They are on the front lines when those travelers come home feeling sick.

- Women of childbearing age: This is the group doctors worry about most. If a woman wasn't vaccinated as a child and didn't get a booster, her pregnancy is at risk.

- Immigrants and refugees: People coming from countries without robust childhood immunization programs may arrive without immunity.

The CRS factor: Why we still care

You might wonder why we bother with the MMR vaccine if the disease is so mild for most people. It's all about Congenital Rubella Syndrome. If a woman catches rubella during her first trimester, there is up to a 90% chance the virus will cross the placenta and damage the fetus.

The virus literally stops cells from dividing correctly. It’s a specialized kind of destruction.

💡 You might also like: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

Dr. Stanley Plotkin, who actually developed the rubella vaccine we use today (the RA 27/3 strain), has spent his career highlighting how preventable these birth defects are. It’s one of the few instances where a vaccine is given to one group (children) primarily to protect another group (unborn babies). It’s an act of collective protection.

Spotting the signs (It's harder than you think)

Rubella is a master of disguise. It looks like a dozen other things.

The rash is usually the first thing people notice. It’s a fine, pink maculopapular rash. Unlike measles, which is deep red and blotchy, rubella is more delicate. It starts on the face and spreads to the trunk and limbs, usually disappearing in the same order it arrived.

Then there are the lymph nodes. Specifically the ones at the base of the skull (suboccipital) and behind the ears (postauricular). They get tender and swollen.

But here’s the kicker: About 25% to 50% of people who get rubella have no symptoms at all. They feel fine. They go to work, they go to the grocery store, they hug their pregnant sister-in-law, and they never know they are shedding the virus. This subclinical spread is why rubella cases in US history were so hard to track before the vaccine.

Comparing Rubella to its "Cousins"

It’s easy to get confused.

📖 Related: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

- Measles (Rubeola): Much more severe. High fever, cough, runny nose, and those "Koplik spots" in the mouth. The rash is intense and lasts a week or more.

- Roseola: Common in toddlers. A very high fever for a few days, which suddenly drops, followed by a rash. It’s caused by a herpes virus, not the rubella virus.

- Scarlet Fever: Caused by strep bacteria. The rash feels like sandpaper and is usually accompanied by a very sore throat.

The current state of testing

If a doctor suspects one of the rare rubella cases in US territory today, they don't just look at the rash and guess. They can't. They need a blood test or a throat swab.

They look for IgM antibodies. If those are present, it usually means a recent infection. They also look for IgG antibodies, which tell you if you’re immune—either from a past infection or from the vaccine. For pregnant women who might have been exposed, these tests are urgent.

Sometimes, if the results are murky, they'll do an "avidity test." This helps determine exactly how long those antibodies have been in the system. It’s high-level detective work performed in labs like the CDC’s Division of Viral Diseases.

What you should actually do about it

Since rubella isn't exactly "going around" the local coffee shop, you don't need to panic. But you do need to be smart, especially if you're planning a family or traveling abroad.

First, check your records. Most people born in the US after 1971 have had at least one dose of MMR. If you were born between 1957 and 1970, you might have only had one dose or none at all.

If you're a woman planning to get pregnant, ask your doctor for a rubella titer test. It’s a simple blood draw that confirms you’re still immune. If you aren't, you can get the vaccine before you conceive. You can't get the MMR vaccine while you are actually pregnant because it’s a "live-attenuated" vaccine, meaning it uses a weakened version of the live virus. While the risk is theoretical, doctors always play it safe.

Actionable steps for 2026:

- Verify Immunity: Locate your immunization records or get a titer test if you're unsure of your status. This is especially vital for healthcare workers and educators.

- Travel Prep: If you're heading to countries with lower vaccination rates, ensure your MMR is up to date at least a month before departure.

- Support Community Immunity: Recognize that your vaccination protects the most vulnerable—specifically pregnant women and those with compromised immune systems who cannot be vaccinated.

- Stay Informed: Keep an eye on local health department advisories if there is a spike in "rash illnesses" in your area.

The reality of rubella cases in US borders is a story of "stable silence." As long as our vaccination rates stay high, the virus stays at the gates. It’s a quiet success, but one that requires us to keep paying attention. We've seen how quickly "eliminated" diseases can come roaring back when we get lazy. Staying protected isn't just about your own health; it's about making sure the 1964 epidemic stays in the history books where it belongs.