If you’ve ever looked at a rough endoplasmic reticulum image in a textbook, you probably saw something that looks like a stack of flattened pancakes or maybe a weirdly folded ribbon. It’s usually colored bright pink or blue to make it pop against the rest of the cell. But honestly? Real life is way messier than those diagrams. When you peer through an actual electron microscope, the rough ER (RER) doesn't look like a clean graphic. It looks like a chaotic, grainy maze. Those grains are the ribosomes, and they are the reason this organelle exists in the first place.

Cells are incredibly crowded. It’s not just empty space in there. Every rough endoplasmic reticulum image captured via Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) shows a cell packed to the gills with membranes. The RER is basically the factory floor of the cell. If the nucleus is the front office giving the orders, the RER is where the heavy lifting happens. It’s where proteins are built, folded, and checked for quality before they get shipped out to do their jobs. Without this "rough" look, you wouldn't be able to digest your lunch or fight off a virus. It's that fundamental.

Why a Rough Endoplasmic Reticulum Image Looks So Grainy

The "rough" part isn't just a creative name. It refers to the millions of ribosomes studded along the surface of the membrane. In a high-resolution rough endoplasmic reticulum image, these look like tiny black dots. Each dot is a protein-making machine. They aren't permanently stuck there, though. They dock and undock based on what the cell needs at that exact moment.

Think of the RER as a massive sheet of fabric that’s been folded over and over to fit inside a small box. These folds are called cisternae. By folding the membrane, the cell creates a massive amount of surface area in a tiny volume. This is biology's way of being efficient. More surface area means more room for ribosomes. More ribosomes mean more protein production. If you’re looking at a cell from the pancreas or the liver, the rough endoplasmic reticulum image will show a massive network because those organs are protein-producing powerhouses. They need the extra space to keep up with the demand for enzymes and hormones like insulin.

The Problem With Textbook Diagrams

Most people get their first glimpse of the RER in a high school biology book. Those drawings are helpful, sure, but they’re also kind of lying to you. They make the RER look static. In reality, it’s a shifting, pulsing network. It’s constantly changing shape.

In a live-cell rough endoplasmic reticulum image—often captured using fluorescent proteins and confocal microscopy—you can actually see the tubules crawling and rearranging. It’s not a stiff structure. It’s more like a lava lamp made of lipids. This movement is vital. If a part of the cell needs more protein synthesis, the RER can literally grow or shift its focus toward that area. Research by Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute has shown just how dynamic these membrane systems are. They aren't just "parts" of a cell; they are a living, moving system.

Decoding the Micrograph: What You’re Actually Seeing

When scientists look at a rough endoplasmic reticulum image from a TEM, they aren't looking for "pretty." They’re looking for health markers. The spacing between the cisternae matters. If the stacks are too far apart or look swollen, it’s a sign of "ER stress." This happens when the cell is overwhelmed and proteins start misfolding. It's a big deal in medical research.

- Ribosomes: Those dark spots on the exterior. They translate RNA into polypeptide chains.

- Lumen: The space inside the folds. This is where the magic happens. Proteins enter the lumen to get their 3D shape.

- Cisternae: The flattened sacs themselves.

Usually, the RER is found right next to the nucleus. This isn't an accident. The instructions (mRNA) come out of the nuclear pores and immediately hit the RER. It's an assembly line. An rough endoplasmic reticulum image showing the RER hugging the nucleus is a snapshot of high-speed communication. The distance between the DNA and the factory is kept as short as possible to prevent errors and save time.

Why Quality Control Happens Here

Not every protein comes out right. Sometimes the "folding" goes wrong. If a protein is misshapen, it can become toxic. The RER has a "quality control" department called the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. Basically, if a protein doesn't look right in the rough endoplasmic reticulum image of the lumen, it gets kicked back out and destroyed.

🔗 Read more: TikTok Profile Pic Viewer: How to See Full Size Photos Without the Drama

If this system fails, you get diseases. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Type 2 diabetes are all linked to "protein misfolding" issues that start right here in the RER. When researchers study these diseases, they spend hours staring at a rough endoplasmic reticulum image to see where the breakdown occurs. They look for "distended" RER, which indicates a backup in the factory. It’s like a conveyor belt that’s jammed because the items at the end aren't being packed correctly.

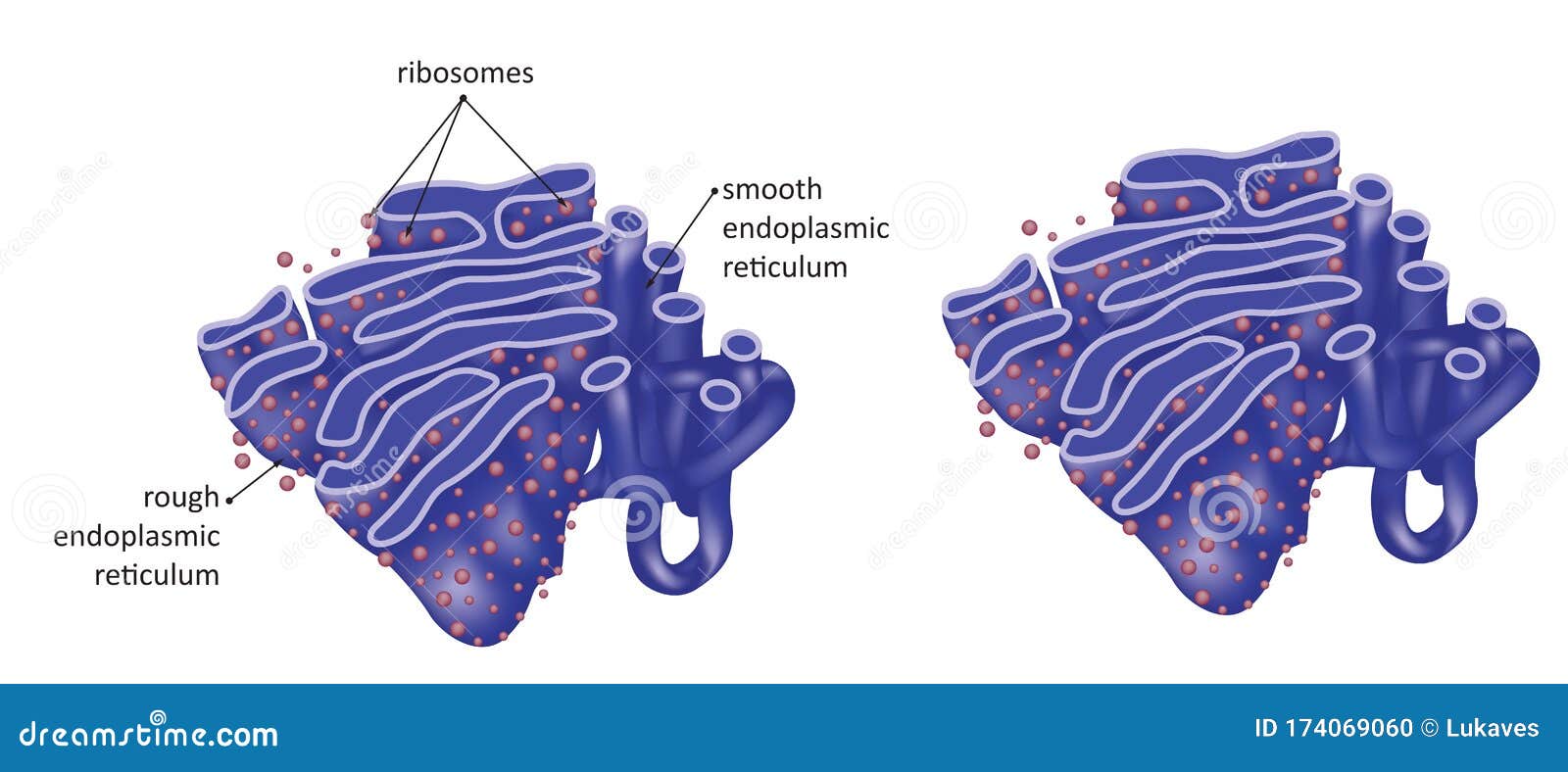

The Difference Between Rough and Smooth ER in Photos

It's easy to get them mixed up if you're just glancing. But in a clear rough endoplasmic reticulum image, the RER looks like sheets. The Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER) looks more like a bunch of interconnected tubes or pipes. No dots.

The SER is more about making lipids (fats) and detoxifying the cell. If you’re looking at a rough endoplasmic reticulum image from a muscle cell, you might see a specialized version called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. It stores calcium. Biology loves to reuse the same basic blueprints for different jobs. The RER is the "heavy industry" version, focused on the massive output of proteins that the cell either needs for its own membrane or needs to export to the rest of the body.

👉 See also: Verizon Wireless Carlisle Pike Mechanicsburg PA: What Most People Get Wrong

How Modern Imaging Has Changed Everything

We used to be limited to black-and-white snapshots. Now, we have 4D imaging. We can watch a rough endoplasmic reticulum image come to life in real-time. Scientists use "Green Fluorescent Protein" (GFP) to tag specific parts of the RER. This allows them to see how the organelle reacts to drugs, toxins, or viruses.

For example, when a virus like COVID-19 or Zika infects a cell, it often "hijacks" the RER. It turns the factory into a virus-producing plant. Looking at a rough endoplasmic reticulum image of an infected cell is wild—the virus literally remodels the RER into "replication organelles." It creates little protected pockets where it can churn out new virus particles away from the cell's defenses. Understanding this architecture is how we develop antivirals.

The Role of Art in Science

Believe it or not, some of the best rough endoplasmic reticulum images are actually 3D reconstructions. Artists work with biologists to turn thousands of thin "slices" of TEM images into a single 3D model. This helps us see the "fenestrations"—basically little windows or holes in the sheets that allow things to move through the cell more easily. It’s not just a solid wall. It’s a porous, flexible, and incredibly complex mesh.

Practical Insights for Students and Researchers

If you're looking for a rough endoplasmic reticulum image for a project or study, don't just settle for the first thing on Google Images. Look for "Micrograph" or "TEM" to see the real thing.

- Check the Scale Bar: Real cells are tiny. A typical RER fold is only about 20-30 nanometers wide.

- Look for the Nucleus: The RER is almost always connected to the outer nuclear membrane. If you see a bunch of grainy folds and no nucleus nearby, it might be a different part of the cell or a very zoomed-in shot.

- Identify the Cell Type: A rough endoplasmic reticulum image from a neuron will look totally different than one from a white blood cell. Context is everything.

The RER is more than just a part of a cell. It is the bridge between the digital information in your DNA and the physical reality of your body. Every muscle fiber, every enzyme in your gut, and every antibody in your blood was born in those grainy folds. When you look at an image of it, you’re looking at the very beginning of "you."

💡 You might also like: The Real Reason Everyone Is Talking About OpenAI Sora and Why You Can’t Use It Yet

Actionable Next Steps

To truly understand this organelle beyond a simple rough endoplasmic reticulum image, start by exploring the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or the Cell Image Library. These databases provide the raw files used by scientists. If you're a student, try comparing a TEM of a healthy cell with one that has been treated with an ER-stress inducer like tunicamycin. Seeing the structural breakdown in the rough endoplasmic reticulum image makes the biology "click" in a way a textbook never can. For hobbyists or those interested in health, researching "ER stress and diet" provides a fascinating look at how what we eat can actually physically alter the shape of these microscopic factories.