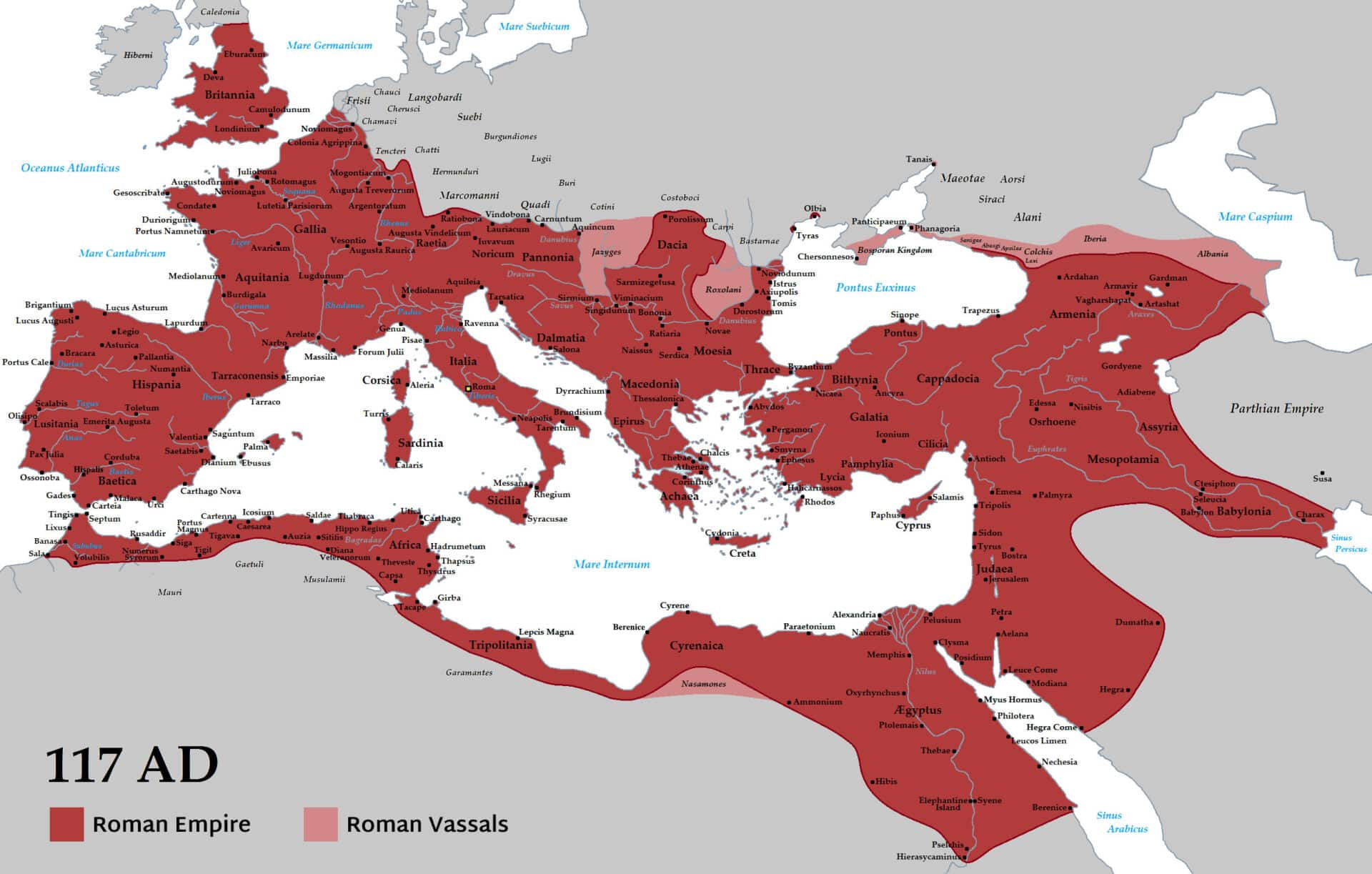

Imagine standing on the edge of the known world in 100 AD. If you were a Roman merchant in Egypt, you were looking across the Red Sea toward a horizon that felt infinite. Meanwhile, thousands of miles to the east, a Han dynasty official was staring at the Taklamakan Desert, hearing rumors of a "Great Da Qin" to the west where people wore silk and lived in cities of stone. Rome and China were the two heavyweights of the ancient world. They were roughly the same size. They both governed about 60 million people. They both struggled with "barbarians" at the gates. Yet, they were like two ships passing in the night, aware of each other's wake but never seeing the hull.

It’s honestly wild when you think about it.

These two superpowers controlled nearly half of the human population. They were the bookends of Eurasia. And yet, for all their power, they were separated by a gap they just couldn't bridge. They knew of each other through a game of "telephone" played by middlemen—Parthians, Kushans, and Sogdians—who got rich making sure the two giants stayed apart.

The Silk Road Game of Telephone

The Silk Road wasn't a highway. It was a brutal, multi-legged relay race. Most people think a Roman merchant just hopped on a camel and rode to Beijing. Nope. Didn't happen. Instead, goods changed hands dozens of times.

Silk moved west. Glass and gold moved east.

The Han Dynasty called the Roman Empire Da Qin. This translates roughly to "Great China." It’s a huge compliment. They basically looked at the vague reports of Rome and thought, "Hey, these guys seem as civilized and organized as we are." They heard the Romans were tall, honest, and had a ton of gold. It was a romanticized vision of a place they couldn't reach.

On the flip side, the Romans called the Chinese the Seres—the Silk People. To the Romans, silk was a scandalous luxury. Pliny the Elder, a famous Roman author and naval commander, actually complained about it. He hated that Roman gold was flowing out of the empire to pay for translucent fabric that "rendered women naked" in public. He estimated that 100 million sesterces left the Roman economy every year just to satisfy the demand for Chinese silk. That is a staggering trade deficit for a pre-industrial economy.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

The Gan Ying Mission: The Closest They Ever Got

In 97 AD, a Chinese general named Ban Chao sent an envoy named Gan Ying to find Rome. This guy actually made it all the way to the "Western Sea," which historians think was either the Persian Gulf or the Black Sea.

He was right on the doorstep.

But then the Parthians—the people living in what is now Iran—stepped in. They were the ultimate middlemen. They realized that if Rome and China started talking directly, the Parthians would lose their massive markup on trade. So, they told Gan Ying some terrifying tall tales. They told him the sea voyage was dangerous, that it could take two years, and that men often died of homesickness on the water.

Gan Ying, being a reasonable guy who didn't want to die in a foreign ocean, turned around. He went home. He was so close. If he had just sailed a few more days, he might have landed in a Roman port. History would have been completely different. It's one of the great "what ifs" of human existence.

A Secret Roman Legion in China?

You might have heard the legend of the "Lost Legion." The story goes that after the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, where the Roman general Crassus was humilitated and killed by the Parthians, a group of Roman prisoners disappeared. Decades later, Chinese records mention a battle against a group of soldiers who used a "fish-scale formation" (which sounds a lot like the Roman testudo) and built wooden palisades.

Some people claim these soldiers settled in a village called Liqian in the Gobi Desert. You can still visit it today. Locals there have green eyes and fair hair.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Honestly? Most historians think it’s a stretch. DNA testing has been inconclusive, showing some Western Eurasian markers, but those could come from any number of groups along the Silk Road. It’s a cool story, but the evidence is thin. Still, it captures our imagination because we want them to have met.

Why the Distance Mattered

Geography is destiny. Between Rome and China sat the Himalayas, the Hindu Kush, and the vast, unforgiving deserts of Central Asia.

Then you had the politics. The Parthian and later Sassanid Empires were the "Iron Curtain" of the ancient world. They guarded the trade routes like hawks. Rome spent centuries fighting the Persians, and China spent centuries fighting the Xiongnu. They were both distracted by their own borders.

The Technological Divide

While both were advanced, they were advanced in different ways.

- Rome was the master of stone, concrete, and maritime engineering. They built roads that you can still drive on today.

- China was the master of metallurgy, paper, and bureaucracy. By the time Rome was still writing on expensive parchment or papyrus, China was developing early forms of paper.

If they had combined Roman engineering with Chinese administrative tech? It would have been a superpower beyond anything we can imagine. But the logistics of 100 AD simply wouldn't allow it. A letter from Rome to Luoyang would have taken a year to arrive—if it arrived at all.

The 166 AD "Embassy"

There is one record in the Hou Hanshu (The Book of the Later Han) that claims an embassy from the Roman Emperor "An-tun" (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus) arrived at the Chinese court in 166 AD.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

They came from the south, likely via the sea route through India and Vietnam. They brought gifts of ivory, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell. The Chinese were actually unimpressed. They thought the gifts were kind of cheap and wondered if the stories of Rome’s greatness were exaggerated.

In reality, these were probably just Roman merchants pretending to be official ambassadors to get an audience with the Emperor. It worked. They opened a sea route that bypassed the Persians, but it never became a massive trade artery. Shortly after this, both empires started to crack. A plague (the Antonine Plague) hit Rome, and the Han Dynasty began to crumble under internal corruption and peasant revolts.

Cultural Mirror Images

It’s fascinating how similar their problems were.

Both empires struggled with the high cost of maintaining a massive standing army. Both had to deal with an elite class that stopped paying taxes while the poor got squeezed. Both eventually saw their frontiers collapse under the weight of migrating tribes.

The Roman Empire eventually split into East and West. The West fell in 476 AD, but the East (Byzantium) hung on. China, after the fall of the Han, went into a period of fragmentation before the Sui and Tang Dynasties unified it again. China’s "cycle" of dynasties allowed it to survive as a unified cultural entity in a way Rome never did.

What This Means for Us Today

We live in a world where you can fly from Rome to Beijing in 10 hours. The barriers that kept these two giants apart are gone. But the "Middleman" problem still exists in global economics. We still see trade wars. We still see empires struggling with the cost of their borders.

History shows us that isolation isn't just about distance; it's about the people in between. The Parthians got rich by keeping Rome and China ignorant of each other. Knowledge, direct contact, and transparency are the only ways to break that cycle.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers:

- Trace the Route: If you want to feel the scale of this distance, don't just visit the Colosseum or the Great Wall. Visit the "in-between" places. Places like Samarkand in Uzbekistan or Dunhuang in China are where the two worlds actually rubbed shoulders.

- Read the Primary Sources: Check out The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan. It reframes world history with the East-West connection at the center. Also, look up the Hou Hanshu—it’s wild to read what Chinese historians actually thought about the "barbarian" Romans.

- Identify the "Middlemen": In your own life or business, look for where "Parthians" might be standing between you and a direct source of information. Direct connection is always more efficient than a relay race.

- Visit Liqian: If you’re ever in Gansu province, China, go to the village of Liqian. Whether the "Lost Legion" story is true or not, the local museum and the unique features of the people there are a testament to how the Silk Road mixed humanity in ways we are still trying to map out.

The story of Rome and China is a reminder that even when we think we are the center of the universe, there is usually someone else on the other side of the world, just as powerful and just as busy, wondering who we are.