You see them on expensive watches. They're carved into the cornerstones of old libraries. Honestly, roman numbers 1 to 500 aren't just some dusty relic from a Latin textbook; they're a weirdly persistent part of how we mark prestige and time. If you’ve ever sat through a Super Bowl or tried to figure out when a movie was actually copyrighted during the end credits, you know the struggle. It's a system that feels complicated until you realize it’s basically just addition and subtraction disguised as letters.

Most people get stuck once they hit the triple digits. Sure, everyone knows I, V, and X. But what happens when you’re staring at a monument and see CDXLIV? It looks like a typo. It isn't. It’s 444.

The Romans didn't have a zero. Think about that for a second. No zero. It changes the entire way you visualize math. Instead of place values like we use in the Hindu-Arabic system (1, 10, 100), they used a subtractive logic that is actually kinda brilliant if you have the patience for it.

The Seven Pillars of the System

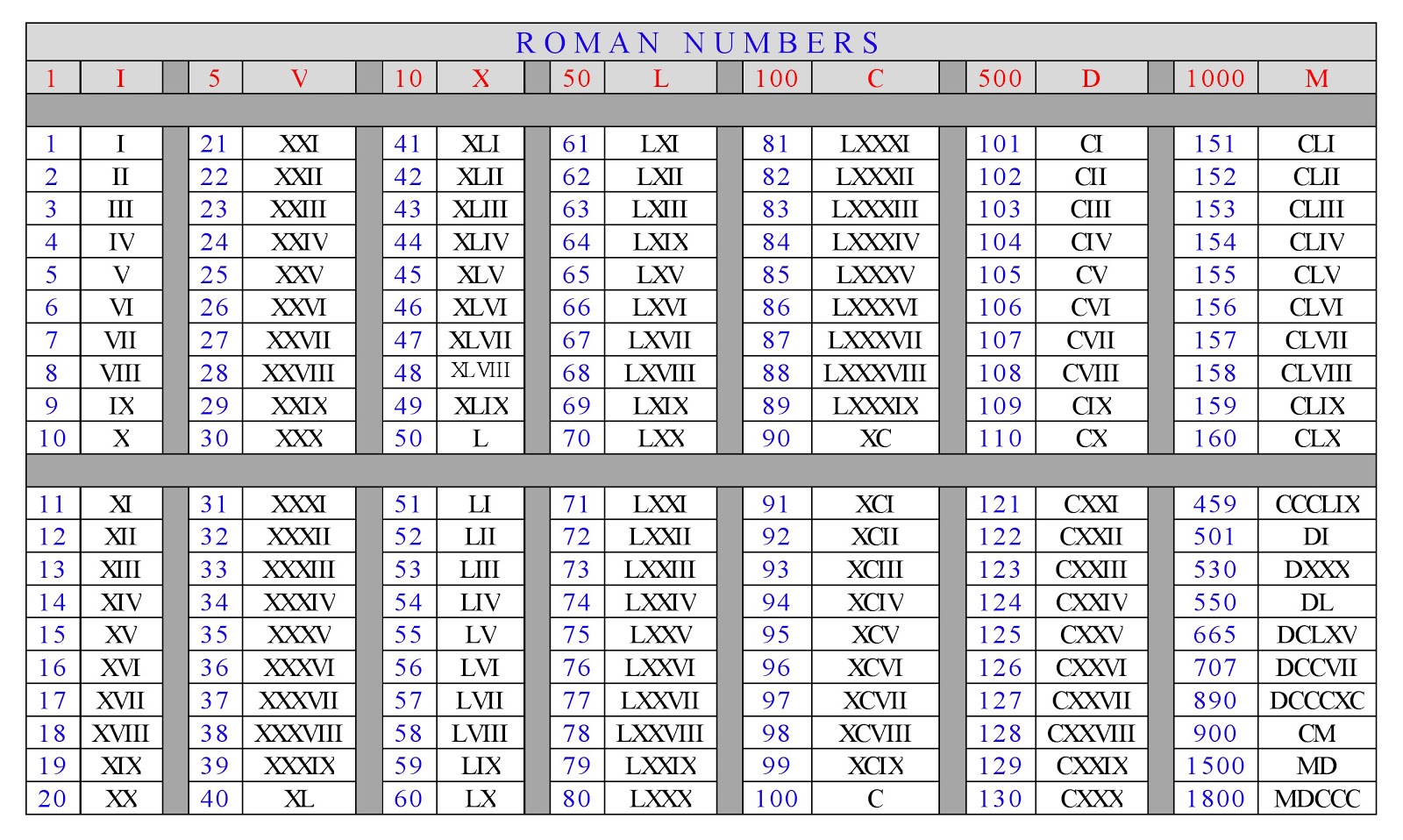

You don't need to memorize 500 different symbols. That would be a nightmare. You only need to know a handful of letters to navigate everything from 1 to 500.

The foundation is simple: I is 1, V is 5, X is 10, L is 50, C is 100, and D is 500. Wait. Where is M?

M is 1,000, but since we are focusing on roman numbers 1 to 500, you won't really need it today. The letter D is your finish line here. It stands for demi-mille, or half a thousand.

Here is where people trip up: the placement. If a smaller value comes after a larger one, you add it. VI is 6. If it comes before, you subtract it. IV is 4. This simple rule is why Roman numerals take up so much horizontal space. To write 388, you need a string of letters: CCCLXXXVIII. It looks like a cat walked across a keyboard, but it’s just 100+100+100+50+10+10+10+5+1+1+1.

Cracking the Code from 1 to 100

Before you can tackle the big stuff, you have to master the first hundred. Most of us are fine until we hit 40. You might want to write IIII, but the Romans (mostly) preferred XL. That’s 10 before 50.

Then you have the 90s. This is the "C" territory. Since C is 100, 90 becomes XC.

Quick Reference for the Tens

- 10 is X

- 20 is XX

- 30 is XXX

- 40 is XL

- 50 is L

- 60 is LX

- 70 is LXX

- 80 is LXXX

- 90 is XC

- 100 is C

It's rhythmic.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

You’ve probably noticed that you never see more than three of the same letter in a row. Well, usually. If you look at an old clock face, you might see IIII for 4 instead of IV. There’s a whole debate among historians about why. Some say it was for visual symmetry with the VIII on the other side. Others think it was to avoid offending the god Jupiter (IVPPITER). Whatever the reason, in standard writing, we stick to the "rule of three."

Navigating the Mid-Range: 101 to 300

Once you pass 100, things actually get a little easier because the pattern just repeats with a C in front.

150? That’s CL.

200? CC.

299? This one is a beast: CCXCIX.

Break it down. CC (200) + XC (90) + IX (9) = 299.

When you’re dealing with roman numbers 1 to 500, the 200s and 300s are the "long" numbers. They take the most ink. 388, which we mentioned earlier (CCCLXXXVIII), is a perfect example of why this system eventually lost out to the decimals we use today. Imagine trying to do long division with that. No thanks.

Historians like James Grout, who runs the Encyclopaedia Romana, point out that while we use these for formal dates now, the Romans used them for everything—from counting soldiers to marking the seats in the Colosseum. If you ever visit Rome, look at the arches above the entrances to the Colosseum. They are numbered. You can still see XLII (42) and XLIII (43) etched into the stone. It’s the ancient version of a stadium ticket section.

The Final Stretch: 400 to 500

This is where the letter D finally enters the chat.

Since D is 500, the number 400 is written as CD.

It’s 100 taken away from 500.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Common Milestones

- CD is 400.

- CDL is 450.

- CDXC is 490.

- CDXCIX is 499.

- D is 500.

Notice the jump between 399 and 400. 399 is CCCXCIX. It’s massive. Then 400 hits and it shrinks down to just two letters: CD. It’s a visual reset.

I’ve always found it interesting that we don't use VD for 495. You’d think 5 subtracted from 500 makes sense, right? But the rules are stricter than that. You can only subtract I from V and X. You can only subtract X from L and C. And you can only subtract C from D and M.

It keeps the math from getting too chaotic, though "not chaotic" is a generous way to describe a system where 488 is CDLXXXVIII.

Why Do We Still Care?

Honestly, it’s about vibes.

Using roman numbers 1 to 500 in 2026 feels "official." If a movie studio puts "Copyright 2026" at the end, it looks like a YouTube caption. If they put MMXXVI, it looks like Cinema.

We use them in outlines to show hierarchy. We use them for Monarchs—King Charles III, not King Charles 3. We use them for the Olympics and the Super Bowl because it makes the event feel like a piece of history rather than just a game that happened in February.

There is also a functional aspect in book publishing. Preface pages are almost always numbered with small Roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv). This allows the publisher to print the main body of the book and the table of contents separately without ruining the page numbering if the introduction runs a little long. It’s a clever hack that has survived for centuries.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don't overcomplicate it.

The biggest mistake is trying to subtract more than one letter. You can't write 8 as IIX. It has to be VIII.

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Another one? Thinking L is 100. It’s not. L is 50. I remember this by thinking "L is for Low" (compared to C). C is for Centum, which is the root of "century" and "cent," so it’s easy to remember that C equals 100.

If you are trying to write a specific year or a number for a tattoo—and please, double-check these before getting inked—break the number into its component parts.

To write 444:

- 400 (CD)

- 40 (XL)

- 4 (IV)

- Result: CDXLIV

Practical Application

If you're teaching this or just trying to get better at reading it, stop trying to translate the whole string at once. Read it like a sentence.

Look for the "anchors"—the Cs and the Ds.

If you see CDXXVII, don't panic.

- CD is 400.

- XX is 20.

- VII is 7.

- 427.

Easy.

Actually, the best way to get fast at this is to look at the copyright dates on old TV shows. Next time you're watching a rerun of an old sitcom, try to decode the year before the screen fades to black. It’s the ultimate nerd party trick.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Roman Numerals

- Memorize the "Big Three" transitions: 40 (XL), 90 (XC), and 400 (CD). These are the only times the pattern breaks from simple addition.

- Practice with the Rule of Three: Never put four of the same symbol in a row. If you find yourself writing IIII, stop and subtract from the next highest five or ten.

- Use the "Expand and Contract" method: Write out the full number in hundreds, tens, and ones before you start picking letters.

- Check the cornerstones: Next time you are downtown, look at the dates on older buildings. Most will fall within the 1800s (MDCCC) or 1900s (MCM), but the principles of the first 500 numbers remain the exact same.

By focusing on the logic of roman numbers 1 to 500, you’re basically learning a shorthand that has lasted two millennia. It’s not about being a math genius; it’s about recognizing the patterns. Once you see the "CD" and "XL" as units rather than individual letters, the whole system opens up.

Keep a cheat sheet for the primary values—I, V, X, L, C, D—on your phone or in a notebook. Use them to date your personal journals or label your files if you want to keep them a bit more private. The more you use them in daily life, the less they look like a foreign language and the more they look like the classic, structural tools they've always been.