You’ve probably seen the "painted tear." It’s a tiny, glistening pearl of liquid on the cheek of a grieving woman, so realistic it looks like it might actually roll off the panel. That single drop of salt water changed art history. For a long time, people thought Jan van Eyck was the only name that mattered in the Northern Renaissance. He was the "optical" guy, the one who could paint a brass pot so well you could see the room reflected in it.

But Rogier van der Weyden was doing something else. Something arguably harder. He wasn’t just painting what eyes see; he was painting what the heart feels.

Honestly, it’s kinda wild how long it took for us to give him his flowers. In his own time, Rogier (or Rogier de le Pasture, if you want to be formal) was a massive celebrity. He was the official city painter of Brussels. He had a workshop so busy it was basically an art factory. While Van Eyck was busy being a courtier, Rogier was creating the visual language of human sorrow that would dominate Europe for a century.

The Mystery of the Late Bloomer

Here is the thing about Rogier van der Weyden that confuses people. He didn't start his apprenticeship until he was about 27. In the 1400s, that was ancient. Most kids were grinding pigments by age 12.

Why the delay?

Some historians, like the legendary Erwin Panofsky, suggested he might have had a university education first. We see "Maistre Rogier" in the records, a title usually reserved for scholars. He finally hooked up with Robert Campin (also known as the Master of Flémalle) in Tournai around 1427.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

It was a powerhouse pairing. Campin was the rough-and-tumble realist. Rogier took that grit and added a layer of high-fashion elegance and spiritual intensity. By 1435, he moved to Brussels, changed his name from the French "de le Pasture" to the Flemish Rogier van der Weyden, and never looked back.

He didn't sign his work. Not a single painting. We only know what's his because of "stylistic DNA" and a few key documents. Imagine being one of the most famous people in Europe and leaving no signature. Total power move.

The Painting That Broke the Internet (in 1435)

If you only look at one work, make it The Descent from the Cross. It’s currently in the Prado in Madrid, and it is a gut-punch of a painting.

Basically, Rogier took the most dramatic moment of the Christian story—taking Jesus down from the cross—and shoved it into a shallow gold box. It’s claustrophobic. There is no background landscape to distract you. You are trapped in that space with ten grieving people.

The Mirror Effect

Look at the Virgin Mary. She’s fainted, and her body is slumped in the exact same shape as her son's. Her hand almost touches his. It’s a visual rhyme. Rogier is telling you that her emotional pain is literally the same as his physical pain.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

The Textures

He was a master of oil. He could paint heavy gold brocade, damp skin, and translucent veils with the same brush. He used layers of glazes to make the colors pop. That red on the figure of Saint John? It’s so deep it looks like you could reach in and grab it.

Why He Still Matters Today

People often ask why we care about a guy who painted altarpieces 600 years ago.

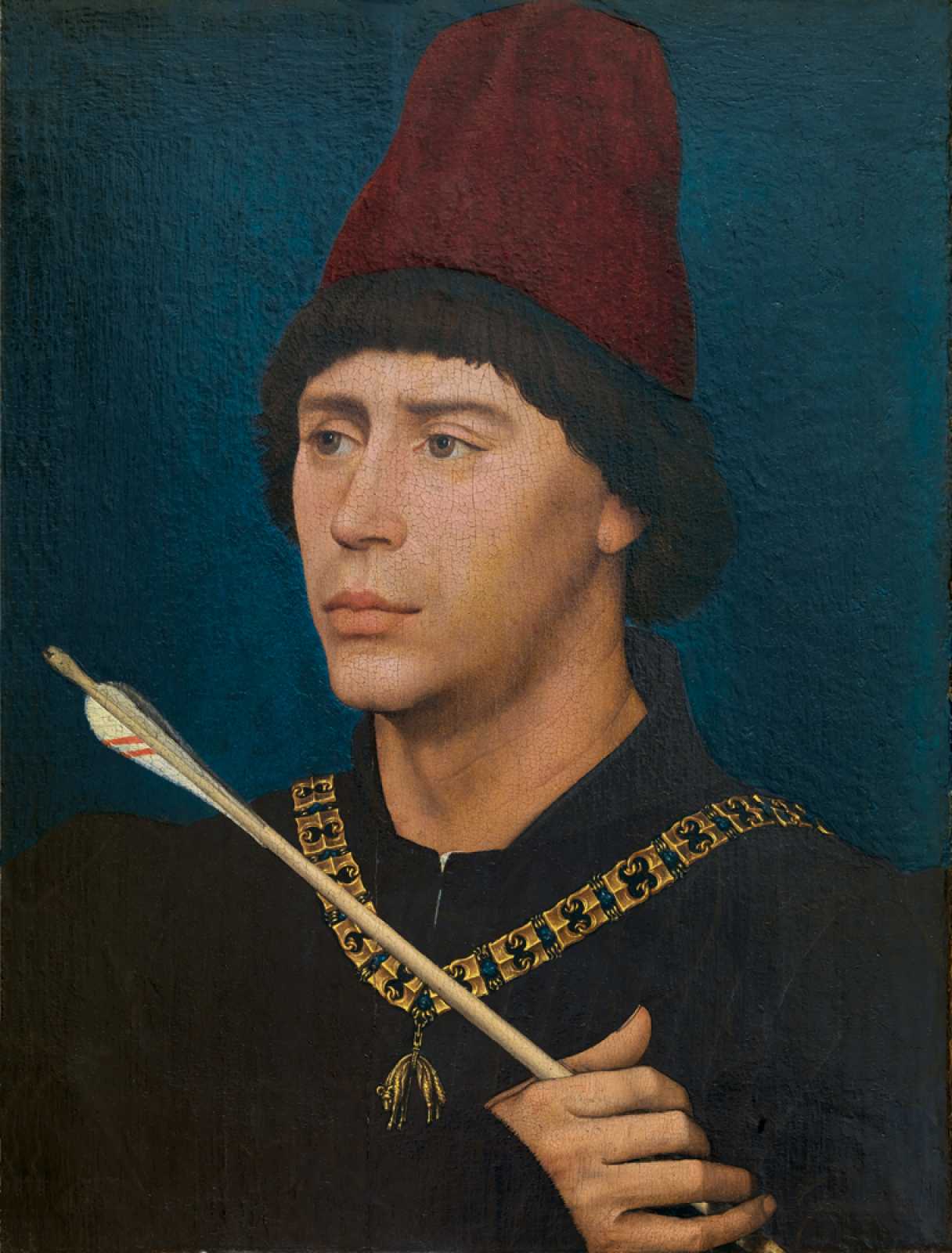

It’s because Rogier van der Weyden invented "the close-up." Before him, religious art was often stiff and symbolic. He made it cinematic. He focused on the psychological interior. When you look at his Portrait of a Lady (the one in Washington), she isn't just a face. She’s a person with a secret. Her fingers are clenched; her eyes are downcast.

He wasn't interested in "perfect" perspective like the Italians. He would bend the rules of space if it made the emotion hit harder. Sometimes he’d make a leg too long or a room too small just to guide your eye to the crying face. He was a manipulator of feelings, a director before cameras existed.

How to Spot a "Rogier" in the Wild

If you’re wandering through a museum and see a 15th-century painting, look for these "Rogierisms":

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

- The Tears: If the characters have wet, glassy eyes or a single perfect tear, start suspecting Rogier.

- The Hands: Long, elegant, almost spider-like fingers. They are never just sitting there; they are always gesturing, praying, or gripping something.

- The Folds: Sharp, "broken" drapery. The fabric doesn't flow in soft waves; it looks like it’s made of stiff paper with crisp edges.

- The Pathos: If you feel like you walked into the middle of a funeral, it’s probably him.

Seeing the Work for Yourself

If you want to do a Rogier pilgrimage, you have a few stops to make.

The Prado in Madrid is the big one. They have the Descent from the Cross and the Durán Madonna. If you’re in London, the National Gallery has The Magdalen Reading, which is actually a fragment of a larger lost painting. It’s a quiet, beautiful moment of a woman lost in a book.

Then there’s the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune, France. He painted a massive Last Judgement altarpiece there. It’s still in the hospital for the poor where it was originally installed. Seeing those screaming souls being dragged to hell while the archangel weighs their deeds is an experience you don't forget.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

Don't just look at the middle of the painting.

With Rogier, the story is in the margins. Look at the tiny plants at the bottom of the cross—he painted them with botanical accuracy. Look at the way a sleeve is pinned. These details aren't just "filler." They are his way of grounding the divine in the everyday.

Next time you’re in a gallery, try this: ignore the labels. Walk through the Northern Renaissance section and see if you can feel the "gravity" of a Van der Weyden before you read the name. You’ll recognize the weight of the grief before you recognize the style.

Next Steps:

- Compare and Contrast: Look at Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait next to Rogier’s Descent from the Cross. Notice how Van Eyck is about "things" and Rogier is about "people."

- Visit Virtually: Use the Prado’s high-resolution digital archives to zoom in on the Descent. You can actually see the individual brushstrokes in the tears.

- Read the Context: Pick up a copy of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. It was the "bestseller" of Rogier’s time and explains why everyone in his paintings is so focused on personal, emotional suffering.