He wasn't supposed to be Sean Connery. That was the whole point. When Roger Moore stepped onto the screen in 1973’s Live and Let Die, the world of cinema was shifting under its own weight. The gritty, post-war tension of the early 1960s had evaporated, replaced by the funk, flare, and slightly ridiculous energy of the 70s. Moore didn't just play James Bond; he reinvented the man to survive an era that would have eaten a more serious spy alive.

People love to argue about the "best" Bond. Usually, they land on Connery for the grit or Daniel Craig for the trauma. But Moore? He’s the one who kept the lights on. He played the character for twelve years across seven films. That’s a massive chunk of cinematic history. If you look at the box office adjusted for inflation, the 007 James Bond Roger Moore era was a powerhouse that essentially saved the franchise from becoming a relic of the Cold War.

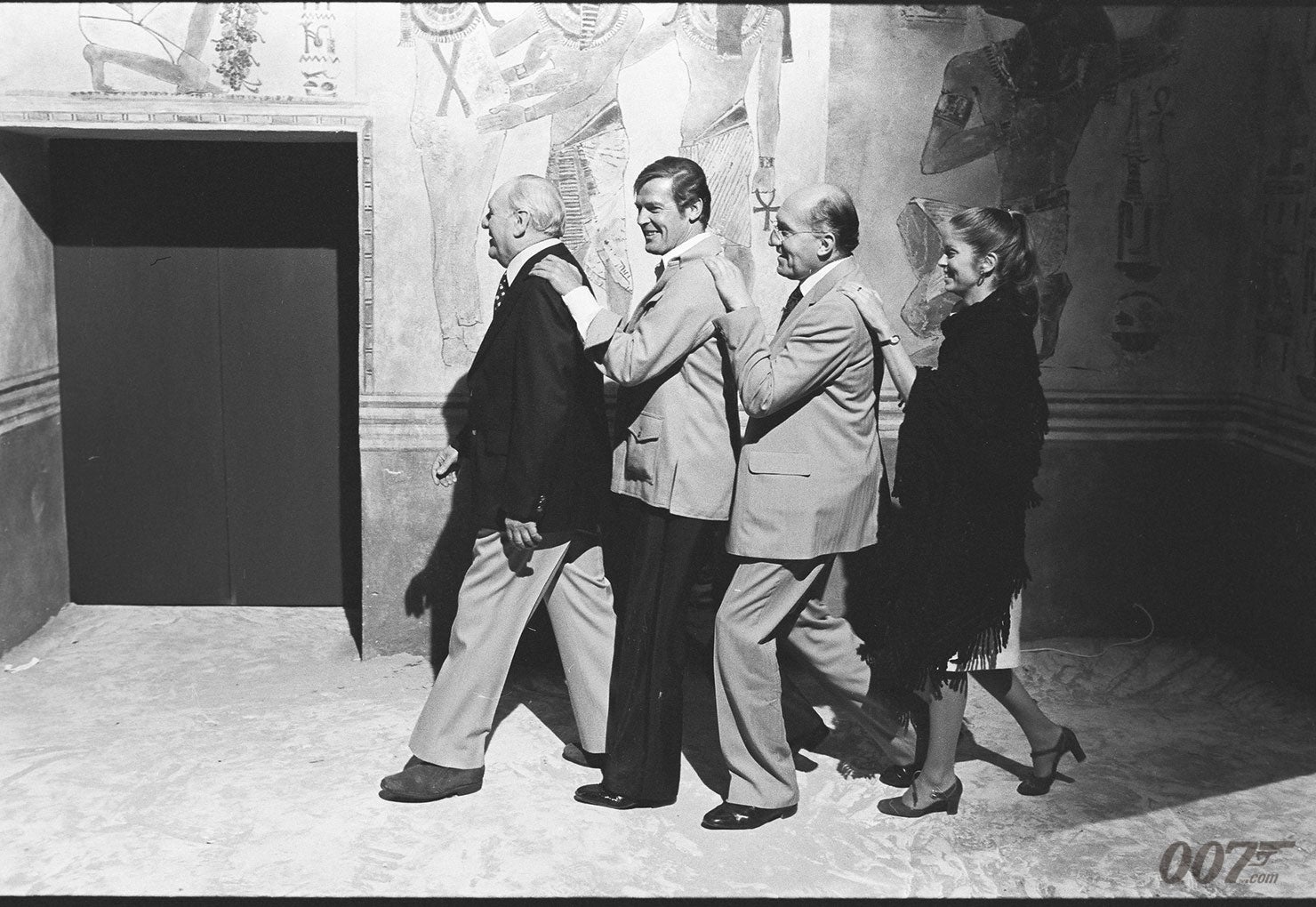

Honestly, he was nearly 007 much earlier. Producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had their eyes on him for Dr. No, but he was tied up with The Saint. It’s wild to think about. If he had started in 1962, the entire DNA of the series would have been lighter from the jump. Instead, he arrived exactly when we needed a wink and a safari suit.

The Man Who Traded the Walther PPK for a Cigar

The transition wasn't seamless. Live and Let Die tried to distance itself from Connery so aggressively that Moore wasn't even allowed to order a martini in the first film. He drank bourbon. He smoked cigars instead of cigarettes. He was posh, sure, but he felt more like a globe-trotting playboy than a government assassin.

Moore’s Bond was defined by a specific kind of levity. While Connery might punch a guy and look disgusted, Moore would raise an eyebrow—the famous "left eyebrow" as it became known—and drop a quip that made you realize he wasn't actually scared. At all. Ever.

Critics often bash this. They say it lacked "stakes." But they're missing the context. By the mid-70s, the world was a mess. The oil crisis, Vietnam, economic stagnation—people didn't go to the movies to see more misery. They went to see a man in a yellow ski suit flip a car over a bridge while a slide whistle played. Yes, the slide whistle in The Man with the Golden Gun is widely hated by purists, but it represents the "all-in" commitment to spectacle that defined the 007 James Bond Roger Moore years.

He was the oldest actor to start the role, at 45. By the time he finished with A View to a Kill in 1985, he was 57. He often joked that he was older than the Bond girls’ mothers, and he wasn't always wrong. Yet, there’s a charm in that longevity. He became the "uncle" of the franchise—the one who knew exactly which wine to pair with fish and how to disarm a nuclear bomb without breaking a sweat or rumpling his tuxedo.

Sci-Fi, Disco, and the Moonraker Gamble

If you want to understand why Moore is polarizing, you have to look at 1979. Star Wars had just changed the world. Eon Productions looked at the landscape and decided Bond needed to go to space. Moonraker is, objectively, insane. It features a laser battle in Earth’s orbit and a cable car fight in Rio.

But here’s the thing: it was a massive hit.

It was the highest-grossing Bond film until GoldenEye came out sixteen years later. Moore’s ability to sell the absurdity is his greatest strength. Could you imagine Timothy Dalton fighting a giant in space? It would have been miserable. Moore, however, leaned into it. He understood that James Bond was a fantasy. He treated the character like a gentleman who happened to find himself in bizarre situations, rather than a soldier on a mission.

Not Just a Comedian: The Darker Side of Moore

It’s a misconception that Moore’s Bond was all laughs. If you revisit For Your Eyes Only, you see a different gear. There’s a scene where Bond kicks a car—with a villain inside—off a cliff. There’s no joke. There’s just a cold, hard stare.

Moore himself reportedly hated that scene. He preferred the "lover not a fighter" approach. He famously hated guns, a result of a childhood accident and a general distaste for violence. This internal conflict actually made his version of the character interesting. He looked like a man who was trying to be a pacifist in a world that wouldn't let him. That tension gave his Bond a layer of sophisticated weariness that often gets overlooked in favor of the gadgets and the puns.

The Ranking Reality

Where does the 007 James Bond Roger Moore filmography actually sit? It’s a rollercoaster.

The Spy Who Loved Me is frequently cited as one of the top three Bond films ever made. It has everything: the Lotus Esprit submarine, the introduction of Jaws (Richard Kiel), and that incredible Union Jack parachute jump. It is the peak of the "Bond as an event" era.

On the flip side, Moonraker and Octopussy are often relegated to the bottom of "serious" lists. But "serious" is a boring metric for these movies. Moore’s films are the most "rewatchable" of the bunch precisely because they don't demand you feel bad for the protagonist. They are travelogues. They are fashion statements. They are escapism in its purest, 35mm form.

Consider the locations. Under Moore, Bond went to:

- The swamps of Louisiana.

- The peaks of the Swiss Alps.

- The canals of Venice (in a gondola that turned into a hovercraft).

- The Taj Lake Palace in India.

- The Golden Gate Bridge.

He wasn't just a spy; he was our tour guide to a world that felt glamorous again.

Correcting the Record on the "Stunt" Era

One thing fans get wrong is the idea that Moore’s era was "lazy." In reality, the stunt work during his tenure was groundbreaking. The corkscrew car jump in The Man with the Golden Gun was the first stunt ever calculated by a computer. The pre-credits sequence in The Spy Who Loved Me remains one of the most dangerous and iconic practical effects in cinema history.

📖 Related: Names of Characters in The Lion King: What Most People Get Wrong About Their Swahili Origins

Moore didn't do all these stunts—he was the first to admit he had a team of doubles for anything more strenuous than walking—but his presence on screen sold the danger. He had a way of looking remarkably composed while everything behind him was exploding. That’s the "Moore Magic."

Critics like Pauline Kael often found him too lightweight, but the public disagreed. He navigated the transition from the psychedelic 60s to the neon 80s without losing his dignity. That’s no small feat. He outlasted disco. He outlasted the original Cold War tropes. He even outlasted the physical toll of the role for a decade longer than most expected.

Legacy of the Safari Suit

We have to talk about the clothes. Moore brought a high-fashion, almost dandy-ish sensibility to the role. Cyril Castle and later Douglas Hayward tailored suits that reflected the changing cuts of the 70s—wider lapels, flared trousers, and those controversial safari jackets.

To modern eyes, some of it looks dated. But in the context of the time, it was peak elegance. He wasn't trying to blend in; he was the center of the room. This fits the Moore philosophy: if you’re going to be a secret agent whose name everyone knows, you might as well look spectacular doing it.

How to Appreciate Moore Today

If you’re a fan of the modern, brooding Bond, Moore can be a shock to the system. The best way to approach his era is to watch them chronologically. You can see the franchise searching for its identity in Live and Let Die, finding its footing in The Spy Who Loved Me, and eventually becoming a self-parody in A View to a Kill.

📖 Related: I Want to Marry Ryan Banks: The ABC Rom-Com That Predicted Our Obsession With Reality TV

There’s a honesty in Moore’s performance. He never tried to convince you he was a lethal killing machine. He tried to convince you that being a spy was the most fun anyone could possibly have. In a world of "gritty reboots" and "dark origins," that perspective is incredibly refreshing.

The 007 James Bond Roger Moore years represent the "Long Saturday Afternoon" of the franchise. They are comfortable, exciting, and deeply colorful. He was the Bond of the people—the one who made the character accessible to a generation of kids who just wanted to see a car turn into a submarine.

Actionable Ways to Explore the Moore Era

To truly understand the impact of Roger Moore on the James Bond legacy, don't just watch the clips. Dive into the craft and the history behind the scenes.

- Watch the "Big Three": If you only have time for a few, watch Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me, and For Your Eyes Only. This trilogy gives you the full range from blaxploitation influence to high-budget spectacle to grounded spy thriller.

- Read Moore’s Memoirs: Roger Moore was a legendary raconteur. His book My Word is My Bond offers a hilarious, self-deprecating look at his time in the role. He doesn't take himself seriously, which makes the stories even better.

- Focus on the Score: The music changed drastically under Moore. Listen to how Marvin Hamlisch and Bill Conti brought disco and funk elements into the classic Bond theme. It’s a masterclass in adapting a brand to a new decade.

- Analyze the Stunts: Watch the making-of documentaries for the Moonraker skydiving sequence or the Live and Let Die boat chase. Seeing the physical risk taken by the stunt teams puts the "campy" reputation of the films into a much more impressive perspective.

- Compare the Villains: The Moore era gave us some of the most iconic foes, from Christopher Lee’s Scaramanga to Yaphet Kotto’s Kananga. Notice how the villains often mirrored the "larger than life" energy Moore brought to the hero.