He was broke. Not "starving artist" broke, but "I'm sleeping on a cot in a Boise hotel" broke. Roger Miller didn't look like a revolutionary in 1964. He looked like a guy who had just finished a residency at a local dive and was wondering where the next meal was coming from. But it was in that exact moment of uncertainty that he saw a sign. It literally said "Trailers for Sale or Rent." Most people would have just kept walking, but Miller had this restless, jittery brain that processed the world through rhyme and rhythm. He started humming. He started snapping. And suddenly, King of the Road began to take shape, eventually becoming a track that would transcend country music to become a global anthem for the disenfranchised and the carefree alike.

It’s weird, isn't it? We think of it as a fun, finger-snapping tune. It’s a staple of karaoke nights and oldies radio. Yet, if you actually listen to what Miller is saying, it’s a song about extreme poverty. It’s about a man who hasn’t seen a "big cigar" in ages, who smokes "old stogies" he finds on the ground, and who knows every lock that isn't locked when the evening sun goes down. It’s a hobo's manifesto.

The Boise Connection and the $1,000 Inspiration

Most people assume a hit like this was manufactured in a Nashville boardroom. Honestly, that couldn't be further from the truth. Miller was actually in Idaho performing when he saw that fateful sign outside a trailer park. He bought a statuette of a hobo at a gift shop, sat down, and tried to channel that specific brand of American nomadism. He didn't finish it right away. It took months. He wrestled with the verses, trying to capture the exact feeling of being "a man of means by no means."

When he finally recorded it in November 1964 at RCA Victor Studios, the magic wasn't in a massive orchestra. It was in the snap. That rhythmic finger-snapping is the heartbeat of the track. It gives the song its swagger. Without that snap, it’s just a sad song about a guy who can't afford a hotel room. With it? He’s the king.

The song was an immediate monster. It hit Number 1 on the US Adult Contemporary chart and stayed there for ten weeks. It crossed over to the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at Number 4. It even won five Grammy Awards in 1965. Think about that for a second. In the middle of the British Invasion, while The Beatles were changing the world, a guy from Texas was winning five Grammys for a song about a guy who cleans up "two-bit rooms" to pay his way.

Why the Lyrics Actually Matter

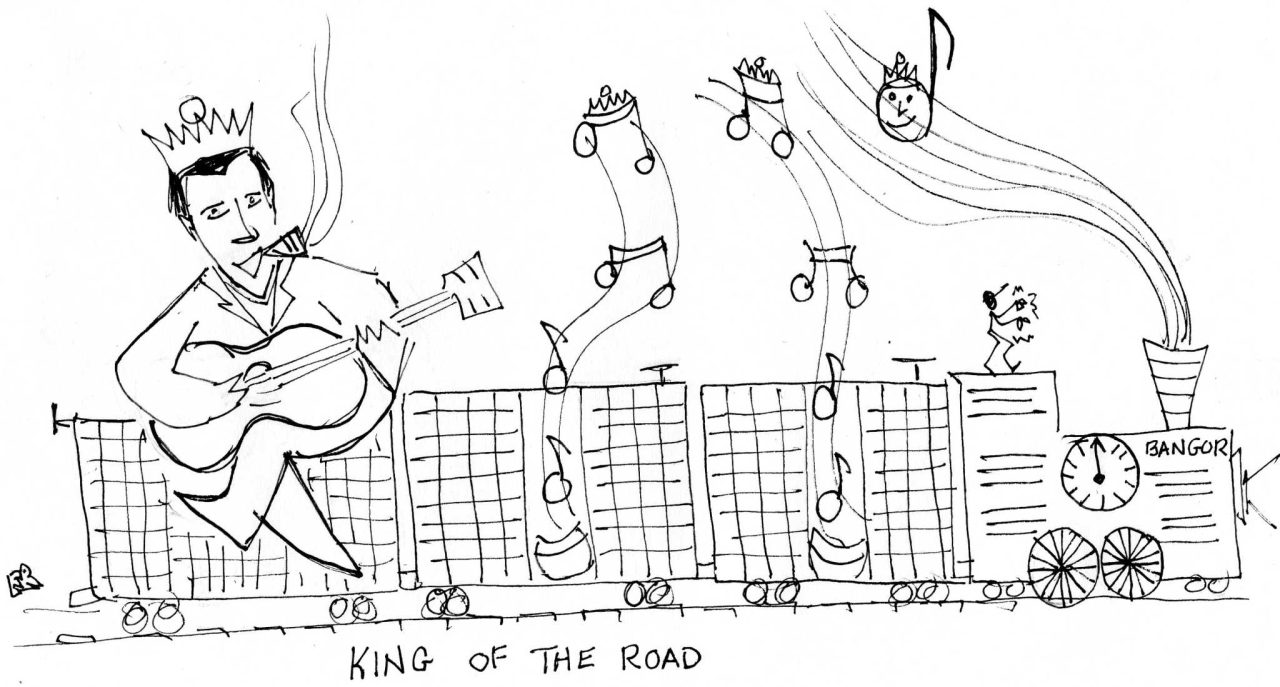

Miller’s writing is deceptively simple. Take the line about "third boxcar, midnight train." It sounds like classic train-hopping imagery. But Miller adds the detail of "destination Bangor, Maine." Why Bangor? Because it fits the rhyme? Partly. But it also emphasizes the distance. He's a long way from home.

👉 See also: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Then there’s the bit about the "old stogies." He specifies they are "short, but not too big around." That’s a man who has spent a lot of time looking at the sidewalk. It’s gritty. It’s real. Miller wasn't writing from a place of high-concept art; he was writing from the perspective of a guy who had spent his early years as a farmhand and a soldier. He knew what it felt like to be dusty.

- The Wage: Two hours of pushing a broom buys an 8x12 four-bit room.

- The Diet: Handouts and whatever else comes his way.

- The Spirit: Totally unbroken. He’s not a beggar; he’s a sovereign citizen of the open road.

The "Wild Child" of Nashville

You can't talk about King of the Road without talking about who Roger Miller actually was. They called him the "Wild Child." He was funny—violently funny. He would walk into a room and just start riffing. Waylon Jennings once said that Roger was the only person he knew who could talk in "neon colors."

But that brilliance came with a cost. Miller struggled with the pressures of fame. He was impulsive. He’d buy a fleet of cars on a whim and give them away. He fought with labels. He didn't fit the mold of the "stiff" country singer in a rhinestone suit. He was more like a jazz musician who happened to play a guitar and sing about trailers. This song gave him the financial freedom to be exactly who he was, even if who he was changed from day to day.

The Impact on Pop Culture

It’s crazy how many people have covered this. Dean Martin did a version that sounds like he’s leaning against a bar with a martini in hand. R.E.M. did a famously drunken, chaotic cover that captures the more desperate side of the lyrics. Even The Proclaimers gave it a go.

But nobody touches the original.

✨ Don't miss: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

There is a specific syncopation in Miller’s voice—the way he says "I'm a..." right before the chorus—that is impossible to replicate. It’s a rhythmic "hiccup" that defines the 1960s Nashville Sound. It was produced by Jerry Kennedy, who understood that Miller’s voice was an instrument of its own. Kennedy let the bass lead and kept the arrangement sparse. This allowed the character of the "hobo" to take center stage.

The Misconceptions About the "Hobo" Lifestyle

We tend to romanticize the road now. We call it "van life." We put it on Instagram with filters. In 1964, being a "hobo" was a grim reality for many. It was a leftover vestige of the Great Depression. Miller’s song took that reality and gave it a sense of dignity.

He isn't asking for your pity. That’s the key.

The "King" in the title isn't ironic. He genuinely feels superior to the people stuck in their 9-to-5 grinds. He has no taxes, no boss, and no stationary home to worry about. He is the master of his own geography. This resonated deeply with a generation that was starting to feel the itch of counter-culture. Before the hippies fully arrived, Roger Miller was singing about dropping out of society.

A Masterclass in Songwriting Economy

The song is less than two and a half minutes long. It’s a miracle of brevity. In that time, we get:

🔗 Read more: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

- A setting (the trailers, the train).

- A character (the broom-pusher).

- A financial statement (four-bit rooms).

- A philosophy (king of the road).

Most modern songwriters would take five minutes and a bridge to explain half of that. Miller does it with a few snaps and a grin. He proves that you don't need a heavy production to make a heavy impact. Sometimes, you just need a good bassline and a truth that people recognize in their bones.

Technical Nuance: The Nashville Sound vs. Roger Miller

In the mid-60s, Nashville was leaning hard into the "Nashville Sound"—lush strings, background choirs, very polished. Think Eddy Arnold. King of the Road thumbed its nose at that. It was lean. It was funky. It had more in common with the jazz clubs of New Orleans than the Grand Ole Opry.

This tension is what made Miller a bridge between genres. He was country enough for the jukeboxes in Georgia but cool enough for the hipsters in New York. He was a "crossover" artist before that term was a marketing buzzword. He won Grammys in both Country and Rock & Roll categories. That just doesn't happen anymore.

Honestly, Miller was a bit of a freak of nature. He could write "Dang Me" and "England Swings" and then turn around and write the entire score for the Tony-winning musical Big River. His range was terrifying. But King of the Road remains the anchor. It’s the song that people will still be humming a hundred years from now because everyone, at some point, has wanted to just hop a train and leave their bills behind.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track Today

If you want to get the most out of this song, don't just listen to it on a tiny phone speaker while you're doing chores. Do this instead:

- Find the original mono mix. The stereo separation in the 60s was often clunky, but the mono mix of this track hits like a punch. The bass and the snaps are centered and powerful.

- Listen to the breathing. Miller uses his breath as percussion. You can hear him prepping for the lines, adding to the "live" feel of the recording.

- Watch the 1960s TV performances. Miller was a physical performer. His facial expressions—half-smirk, half-weariness—add a whole new layer to the lyrics.

- Compare it to "Dang Me." Listen to the two back-to-back. You’ll see how Miller used similar rhythmic tricks but applied them to two completely different emotional landscapes.

King of the Road isn't just a song; it's a piece of American sociology set to a catchy beat. It reminds us that status is subjective. You can have nothing in your pocket and still be a king, as long as you're the one holding the map. Miller lived that life, he wrote that life, and in the end, he invited us all to snap along with him. It’s a masterclass in songwriting that reminds us why we fell in love with music in the first place—it makes the hard parts of life feel a little more like a parade.