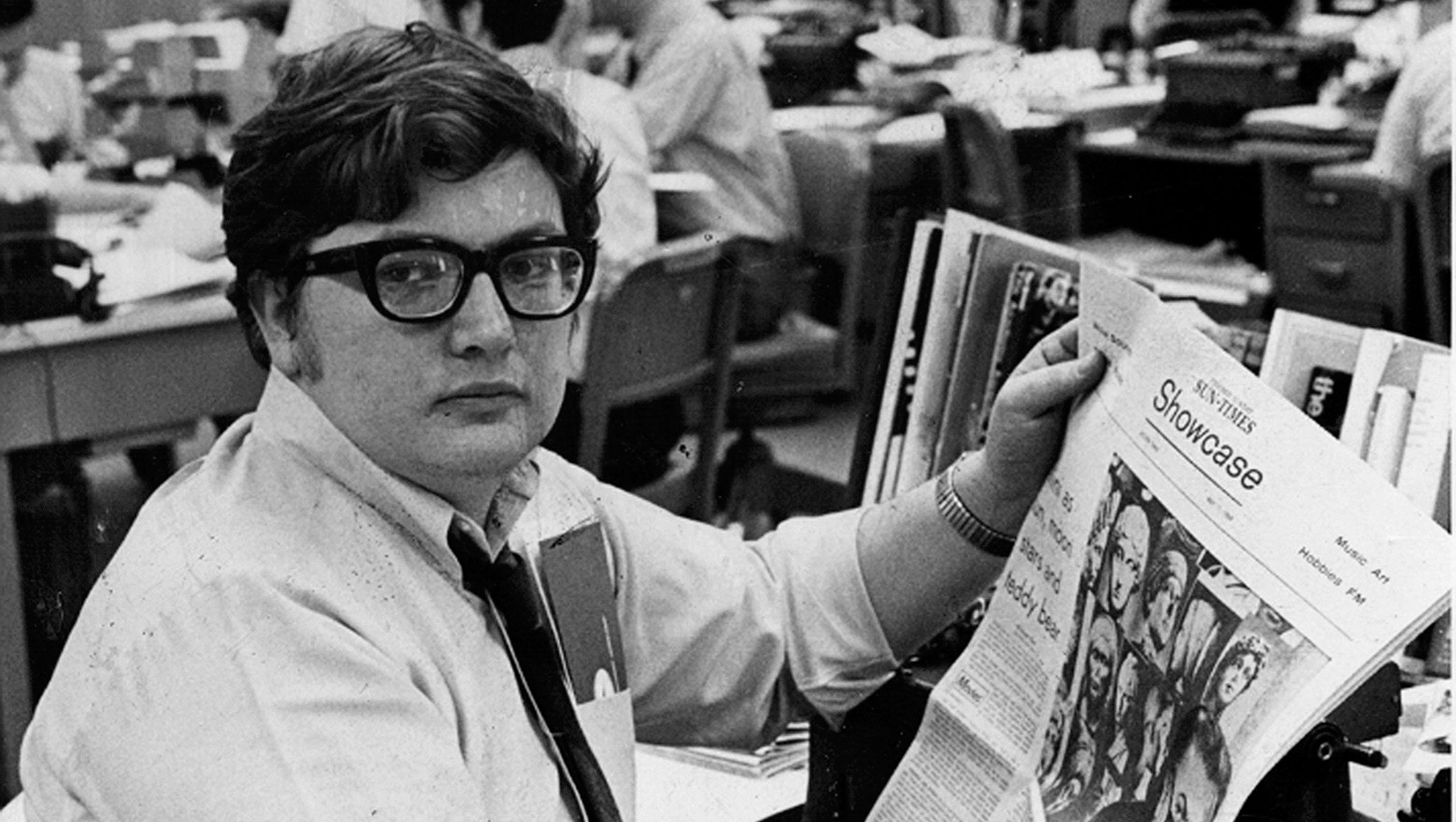

Roger Ebert didn't hate gamers. Honestly, he didn't even hate the games themselves. But back in 2010, the legendary film critic set the internet on fire by typing five words that became the ultimate "old man yells at cloud" moment in digital history: Video games can never be art. The backlash was instant. It was brutal. Thousands of comments flooded his blog, many from people who felt their entire lives were being dismissed by a guy who had probably never held a PlayStation controller.

Looking back, the whole thing was kinda bizarre. Ebert was a Pulitzer Prize winner who championed indie films and pushed for "difficult" cinema. Yet, when it came to the most explosive medium of the 21st century, he dug his heels in. He wasn't just being a contrarian; he was defending a very specific, old-school definition of what it means to create something.

The Battle of Definitions: Why Ebert Said "Never"

The core of the Roger Ebert video games argument wasn't about the graphics. It wasn't about the violence. It was about control.

✨ Don't miss: Powerball Numbers for Connecticut: What You Might Be Getting Wrong

Ebert believed that art requires a singular vision. If you’re watching a movie, the director decides exactly where you look and how you feel. If you’re reading a book, the author controls the pace. But in a game? You're the one in charge. You can walk into a wall for ten minutes or skip the dialogue. To Ebert, that interactivity destroyed the "authorial control" necessary for high art.

He basically argued that once you add the ability to "win," you’re no longer in the realm of art. You’re in the realm of sports or hobbies. He famously noted that Bobby Fischer or Michael Jordan never claimed their games were art, so why were gamers so desperate for the label?

"I tend to think of art as usually the creation of one artist... one obvious difference between art and games is that you can win a game. It has rules, points, objectives, and an outcome." — Roger Ebert, 2010.

It sounds pedantic now. In fact, it sounded pedantic then. He even took a shot at Kellee Santiago’s TED talk, where she used games like Flower and Braid as examples of the medium's evolution. Ebert called them "pathetic" compared to the great poets and filmmakers. Ouch.

✨ Don't miss: Why Def Jam: Fight for NY is Still the King of Combat Games

Did He Ever Actually Play Them?

This is the part that usually gets gamers the most heated. No, he didn't really play them. At least, not the modern ones that would have changed his mind.

He was once offered a free PlayStation 3 and a copy of Flower to see if it would change his perspective. He turned it down. He admitted he was arguing on purely theoretical grounds. It’s like a guy reviewing a restaurant based on the menu and a few photos he saw on Yelp without ever actually tasting the food.

However, there is a weird footnote in his history. Back in 1994, Ebert actually reviewed a CD-ROM "game" called Cosmology of Kyoto for Wired. He loved it. He called it an "enchanting" experience. But because it didn't have traditional winning or losing, he didn't really categorize it with the "games" he would later rail against.

The "Okay, Kids" Apology

By July 2010, the heat got to be too much. Ebert published a follow-up post titled "Okay, kids, play on my lawn."

💡 You might also like: Stuck on a 5 Letter Word Ending in INT? Here is How to Solve It

It wasn't a full surrender. He didn't suddenly start grinding for loot in World of Warcraft. But he did admit he was a "fool" for mentioning video games in the first place. He conceded that he shouldn't have expressed an opinion on something he hadn't experienced.

He wrote that it was "quite possible" a game could someday be great art, even if he didn't think he’d live to see it. It was a classic "let's agree to disagree" move. He realized he was trying to protect a border that had already been crossed by millions of people.

Why the Roger Ebert Video Games Debate Still Matters in 2026

You might think a decade-old blog post doesn't matter anymore. But look at the "Prestige TV" era of gaming. Shows like The Last of Us on HBO or the cinematic depth of God of War: Ragnarök have basically won the war Ebert started.

We don't ask if games are art anymore. We just argue about which ones are masterpieces.

Ebert’s mistake was thinking that interactivity and art were mutually exclusive. He didn't see that the player's choice is the brushstroke. When you make a difficult moral decision in a game, that is the artistic experience. It’s not a lack of control; it’s a new kind of collaboration between the creator and the audience.

Actionable Insights for Modern Critics

If you're writing about games or trying to explain their value to someone who "doesn't get it," keep these points in mind:

- Avoid the "Validation" Trap: We don't need a film critic's permission to call something art. The impact on the audience is the only metric that matters.

- Focus on Mechanics as Metaphor: When a game's rules (like the time-rewind in Braid) reflect its story, that’s where the "high art" happens.

- Acknowledge the Gatekeepers: Ebert represented the "Old Guard." Understanding their fear of losing authorial control helps us explain why interactivity is a strength, not a weakness.

Roger Ebert was arguably the greatest film critic who ever lived. He taught us how to love movies. But when it came to the digital frontier, he stayed behind the velvet ropes. He died in 2013, still mostly a skeptic, but his stubbornness actually helped the gaming community define what it stands for. By forcing us to defend why games matter, he accidentally made us better critics of our own favorite hobby.